The original Caltech news release by Katie Neith can be read here.

Deep inside the Earth, seismic observations reveal that three distinct structures make up the boundary between the Earth's metallic core and overlying silicate mantle at a depth of about 2,900 kilometers—an area whose composition is key to understanding the evolution and dynamics of our planet. These structures include remnants of subducted plates that originated near the Earth's surface, ultralow-velocity zones believed to be enriched in iron, and large dense provinces of unknown composition and mineralogy. A team led by Caltech's Jennifer Jackson working at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), an Office of Science user facility, has new evidence for the origin of these features that occur at the core-mantle boundary.

“We have discovered that bridgmanite, the most abundant mineral on our planet, is a reasonable candidate for the material that makes up these dense provinces that occupy about 20 percent of the core-mantle boundary surface, and rise up to a depth of about 1,500 kilometers. Integrated by volume that's about the size of our moon!” said Jackson, coauthor of a study that outlines these findings and appears in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. “This finding represents a breakthrough because although bridgmanite is the Earth's most abundant mineral, we only recently have had the ability to precisely measure samples of it in an environment similar to what we think the materials are experiencing inside the Earth.”

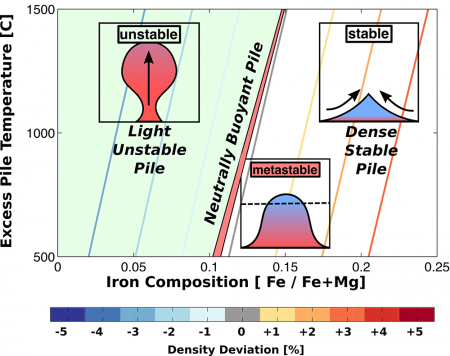

Previously, said Jackson, it was not clear whether bridgmanite, a perovskite structured form of (Mg,Fe)SiO3, could explain seismic observations and geodynamic modeling efforts of these large dense provinces. She and her team show that indeed they do, but these structures need to be propped up by external forces, such as the pinching action provided by cold and dense subducted slabs at the base of the mantle (Fig.1).

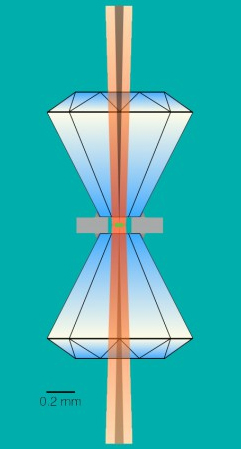

Jackson, along with then Caltech graduate student Aaron Wolf, now at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, and researchers from the University of Hawaii and The University of Chicago came to these conclusions by taking precise x-ray measurements of synthetic bridgmanite samples compressed by diamond anvil cells to over 1 million times the Earth's atmospheric pressure and heated to thousands of degrees Celsius (Fig. 2).

The measurements were done utilizing two different x-ray beamlines at the Argonne APS, where the team used powerful x-rays to measure the state of bridgmanite under the physical conditions of the Earth's lower mantle to learn more about its stiffness and density under such conditions. Pressure-volume-temperature diffraction experiments were conducted at the GeoSoilEnviroCARS (GSECARS) beamline 13-ID-D, utilizing the gas-loading system at GSECARS. In addition, the unique capabilities at X-ray Science Division beamline 3-ID-B were employed to constrain the site-specific behavior of iron in the bridgmanite. Both the GSECARS gas loading system and the 3-ID-B capabilities are resources supported by the Consortium for Materials Properties Research in Earth Sciences (COMPRES), a community-based consortium whose goal is to enable Earth Science researchers to conduct the next generation of high-pressure science on world-class equipment and facilities.

The density controls the buoyancy—whether or not these bridgmanite provinces will lie flat on the core-mantle boundary or rise up (Fig. 1). This information allowed the researchers to compare the results to seismic observations of the core-mantle boundary region.

“With these new measurements of bridgmanite at deep-mantle conditions, we show that these provinces are very likely to be dense and iron-rich, helping them to remain stable over geologic time,” said Wolf.

Using the synchrotron Mössbauer spectroscopy x-ray research technique, the team also measured the behavior of iron in the crystal structure of bridgmanite, and found that iron-bearing bridgmanite remained stable at extreme temperatures (more than 2000° Celsius) and pressure (up to 130 gigapascals). There had been some reports that iron-bearing bridgmanite breaks down under extreme conditions, but the team found no evidence for any breakdown or reactions.

“This is the first study to combine high-accuracy density and stiffness measurements with Mössbauer spectroscopy, allowing us to pinpoint iron's behavior within bridgmanite,” said Wolf. “Our results also show that these provinces cannot possibly contain a large complement of radiogenic elements, placing strong constraints on their origin. If present, these radiogenic elements would have rapidly heated and destabilized the piles, contradicting many previous simulations that indicate that they are likely hundreds of millions of years old.”

In addition, the experiments suggest that the rest of the lower mantle is not 100 percent bridgmanite as had been previously suggested. “We've shown that other phases, or minerals, must be present in the mantle to satisfy average geophysical observations,” said Jackson. “Until we made these measurements, the thermal properties were not known with enough precision and accuracy to uniquely constrain the mineralogy.”

“There is still a lot of work to be done, such as identifying the dynamics of subducting slabs, which we believe plays a role in providing an external force to shape these large bridgmanite provinces,” she said. “We know that the Earth did not start out this way. The provinces had to evolve within the global system, and we think these findings may help large-scale geodynamic modeling that involves tectonic plate reconstructions.”

This work has been highlighted by the Archaeology News Network, (e) Science News, myScience.org, and Phys.org.

See: Aaron S. Wolf1,2*, Jennifer M. Jackson2**, Przemeslaw Dera3,4, and Vitali B. Prakapenka4, “The thermal equation of state of (Mg, Fe)SiO3 bridgmanite (perovskite) and implications for lower mantle structures,” J. Geophys. Res. 120(11), 7460 (2015). DOI: 10.1002/2015JB012108

Author affiliations: 1University of Michigan, 2California Institute of Technology, 3University of Hawaii, 4TheUniversity of Chicago

Correspondence: *aswolf@umich.edu, **jackson@gps.caltech.edu

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation CSEDI EAR-1161046, CAREER EAR-0956166, and the Turner Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of Michigan. GeoSoilEnviroCARS is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF)-Earth Sciences (EAR-1128799) and Department of Energy- GeoSciences (DE-FG02-94ER14466). Sector 3 operations and use of the gas loading system at GSECARS are supported by COMPRES under NSF Cooperative Agreement EAR 11-57758. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.