A small gas molecule, nitric oxide, NO, once thought to be nothing more than a poison turns out to be an important neurotransmitter involved in regulating our blood pressure, sexual arousal, and other biological functions. Understanding how it is made in our bodies by a group of enzymes that process the amino acid arginine could lead to new ways to controlling NO release and fixing problems such as high blood pressure and sexual dysfunction. Model compounds of the flat iron porphyrin systems found in the active site of several enzymes and the oxygen-carrying center in the blood protein hemoglobin reveal important clues about function and form. Given that the same iron-porphyrin system is so critical in the processing of the neurotransmitter NO, and the transport of the toxic gas carbon monoxide (CO) as well as oxygen (O2), research carried out at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) could lead to important insights about how our bodies use and are harmed by small gas molecules.

Nitric oxide is a small molecule that exists as a gas, but in the body it is an important signaling molecule, or neurotransmitter. Its involvement in blood pressure regulation through the dilation of blood vessels makes it a vital key to many physical processes. Indeed, the role of NO is inextricably linked to heart function and the release of NO from the drug nitroglycerin is explained by this role.

The researchers in this study, from the University of Notre Dame, Northeastern University, and Argonne National Laboratory hoped to explain how these iron porphyrin compounds in proteins can discriminate between the different small molecules - NO, CO, and O2 - with which they interact, something that was not apparent previously. They point out that studies using vibrational spectroscopy have not generally been fruitful in unraveling the properties of the active site and how different chemical bonding interactions between gas molecule and the iron-porphyrin center give rise to the discriminatory behavior of the same group present in different proteins, whether enzyme or hemoglobin.

They utilized nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy (NRVS), a synchrotron-based measurement carried at the X-ray Science Division Sector 3-ID-B,C,D x-ray beamline at the Argonne APS, an Office of Science user facility. They concentrated on oriented single crystals to get a clearer picture of the interactions beyond the insights that would be available through an x-ray crystal structure determination alone. The NRVS data they obtained allowed them to probe the low-frequency vibrations of chemical bonds between a nitric oxide molecule, or nitrosyl group, attached to one of two different iron-porphyrin compounds acting as molecular models of the natural units found in the enzyme, a synthetic heme group.

By observing the spectra of the crystals of these compounds from two different directions at right angles to each other, the team teased apart the various vibration modes of the bonds connecting the iron atom to the NO group and to the flat porphyrin molecule. Vibrational motions of the iron atom in the first, easily synthesized iron-porphyrin complex, were found to differ significantly along two directions parallel to the plane of the molecule, but rotated by 90° in the plane.

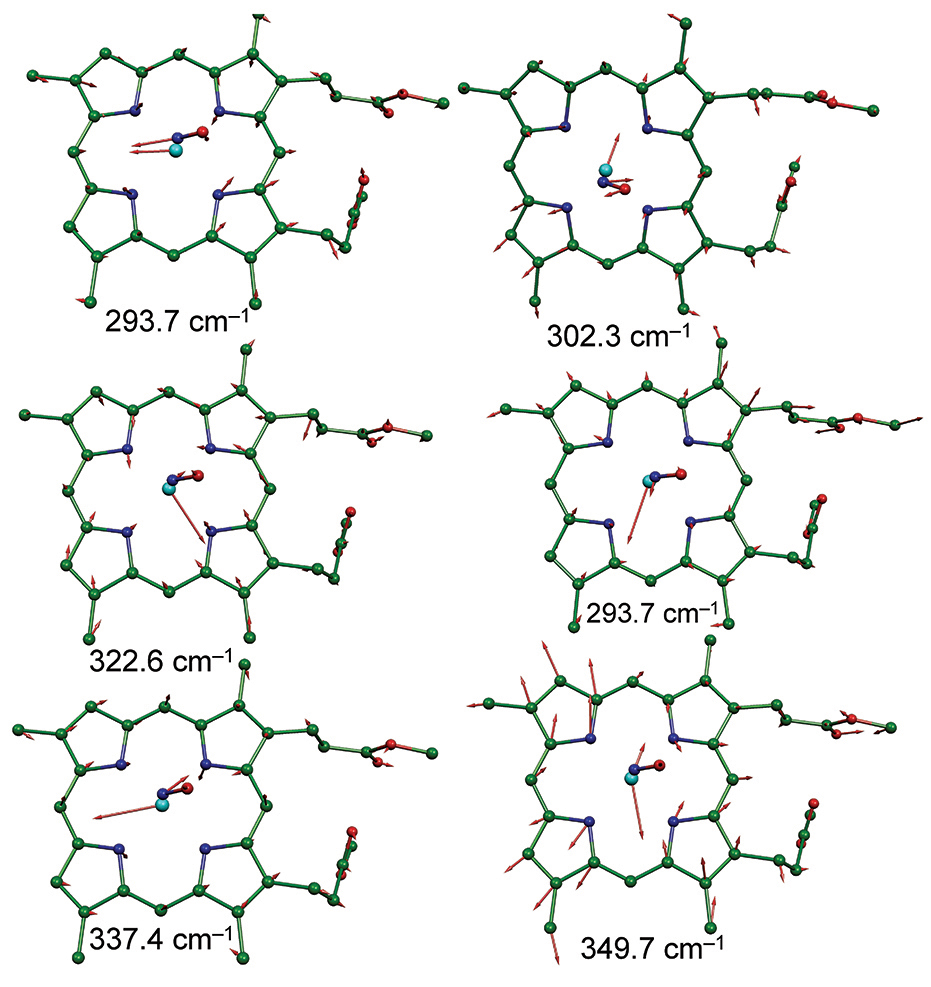

A second, more sophisticated model compound offered a similar distinction. The team then used computational chemistry, in the form of density functional theory (DFT) to help them explain why this might be so (see the figure). Fundamentally, it is the orientation of the bent bond between the iron atom at the porphyrin center and the attached N-O group attached to it, the Fe-N-O bond, in other words, that give rise to the different spectra dependent on the angle at which they are measured. The orientation of the Fe-N-O unit controls the vibration of the iron atom within the plane of the porphyrin group.

The team suggests that this off-axis tilting of the Fe-N-O unit and its influence on bonding highlights how unusual the NO molecule is despite its small size and superficial simplicity.

The degree of vibration seen in different directions is related to the strength of the bond between the iron center and the NO group, as opposed to other small molecules, such as CO or O2, and given that the team used an iron-porphyrin group closely resembling that found in the NO enzyme, the finding provides a new clue as to the natural affinity of the enzyme for its target molecule, NO. — David Bradley

See: Jeffrey W. Pavlik1, Qian Peng1, Nathan J. Silvernail1, E. Ercan Alp2, Michael Y. Hu2, Jiyong Zhao2, J. Timothy Sage3*, and W. Robert Scheidt1**, “Anisotropic Iron Motion in Nitrosyl Iron Porphyrinates: Natural and Synthetic Hemes,” Inorg. Chem. 53, 2582 (2014). DOI: 10.1021/ic4028964

Author affiliations: 1University of Notre Dame, 2Argonne National Laboratory, 3Northeastern University

Correspondence: * jtsage@neu.edu, ** scheidt.1@nd.edu

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grant GM-38401 to W.R.S. and the National Science Foundation under CHE-1026369 to J.T.S. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov