Bacteria and fungi have been engaged in molecular warfare for millions of years. This means they have perfected ways to get past the defenses of other organisms and have also devised ways to keep them out. This arms race was revealed in 1928 when Alexander Fleming returned from his holidays to discover a petri dish of bacteria in which a fungus had started to grow and was killing the bacteria around it. He immediately realized the potential value of these antibiotic molecules to humans for curing disease.

Now, however, our widespread use of natural antibiotics has led to the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria and an urgent need to develop some new molecular weapons of our own. With that in mind, a research group from the University of Michigan conducted a substrate-trapping study of bacterial enzymes that make an important class of antibiotics. The research provides important new information that will facilitate the design of new enzymes to make novel antibiotics that can overcome antibiotic resistance.

The group used the resources of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and National Cancer Institute Structural Biology Facility (GM/CA) at beamlines 23-ID-B and 23-ID-D at the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility at DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory.

The research focused on bacterial thioesterase (TE) enzymes that perform a critical step in a synthetic pathway to make macrolide antibiotics such as erythromycin and pikromycin. These TE enzymes temporarily attach antibiotic precursors to a nucleophilic amino acid in the TE, check the structural integrity of the precursor substrates, and then convert them to either a) a cyclic lactone molecule via nucleophilic attack by an oxygen atom in the substrate, or to b) a linear final product via attack by a water molecule. Although the structures of five TE enzymes that generate various products have been solved, the process by which a product is cyclized or hydrolyzed is poorly understood.

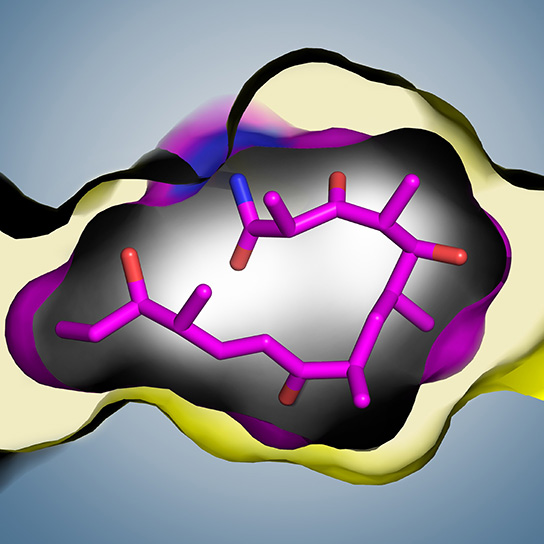

To get a clearer picture of the final step in the antibiotic synthesis process that might help researchers to understand the parameters needed to make new antibiotics, the team decided to use a technique called substrate trapping to visualize the moment of decision between cyclization and hydrolysis in different TE enzymes. They used a new substrate trapping technique that incorporates a non-natural amino acid into the active site in place of the natural serine or cysteine nucleophile. The bond attaching a substrate to serine or cysteine is unstable, but the non-natural amino acid traps the reaction intermediate as a stable amide group (see Figure).

After testing five bacterial TE enzymes to see if they could successfully incorporate the substrate trap, two of substrate trapping proteins could be purified in sufficient amounts for further testing, one that makes erythromycin and one that makes pikromycin, both cyclic antibiotics.

With the substrate trap in place, the team tested various substrates and observed that the pikromycin TE enzyme was very selective for its natural substrate, with limited tolerance for other substrates, while the erythromycin TE enzyme had a much broader tolerance for non-natural substrates. The reason for this was revealed when team was able to crystallize the pikromycin TE enzyme, solved a structure to 2.8 Å, and showed that the substrate enters a very snug active site that forces it into a U-shape so that the site for nucleophilic attack and cyclic lactone formation is close to the oxygen nucleophile on the substrate. This remarkable “hand-in-glove” fit of substrate within the enzyme active site explains both the selectivity of the enzyme and its ability to quality check the substrate, as there is very little room for variation in the side groups on the incoming substrate.

In order to understand these TE active sites further, the team solved the structures for three more wild type TE enzymes (without the substrate trap) and compared them to the pikromycin TE data. Modeling was used to place various substrates into the active site of the structures for these comparisons. The comparisons revealed similar overall TE enzyme structures with significant variability in the active sites. The TE enzymes that form cyclic products have snug active sites that curl the product to facilitate the nucleophilic cyclization reaction and avoid water molecules that might cause hydrolysis while those that form linear products have slender active sites that are too narrow to allow cyclization.

Through the successful incorporation of a non-natural amino acid, the team observed that some TE enzymes can form non-natural products, paving the way for using these enzymes to engineer new antibiotics. – Sandy Field

See: T. McCullough1, V. Choudhary1, D.L. Akey1, M.A. Skiba1, S.M. Bernard1, J.D. Kittendorf1, J.J. Schmidt1, D.H. Sherman1, J.L. Smith1, “Substrate trapping in polyketide synthase thioesterase domains: structural basis for macrolactone formation,” ACS Catal 2024, 14, 16, 12551-12563 (Aug. 2024)

Author affiliations: 1University of Michigan.

The work was supported by NIH grant R01 DK042303 and the Rita Willis Professorship to J.L.S. and by NIH grant R35 GM118101 and the Hans W. Vahlteich Professorship to D.H.S. V.C. was supported by NIH training grant T32 GM140223. GM/CA@APS has been funded by the National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM-12006, P30GM138396). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS at Argonne National Laboratory is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.