Polarons are quantum entities that arise in crystalline solids due to interactions between electrons and quantized lattice vibrations (phonons). Characterizing polaron behavior is important to scientists because they can play an important role in solid-state phenomena such as thermoelectricity, ferroelectricity, magnetoresistance, and high-temperature superconductivity. While polarons have been extensively investigated in bulk (3D) lattices, few investigations have probed polarons in one- and two-dimensional crystalline structures.

Polarons are quantum entities that arise in crystalline solids due to interactions between electrons and quantized lattice vibrations (phonons). Characterizing polaron behavior is important to scientists because they can play an important role in solid-state phenomena such as thermoelectricity, ferroelectricity, magnetoresistance, and high-temperature superconductivity. While polarons have been extensively investigated in bulk (3D) lattices, few investigations have probed polarons in one- and two-dimensional crystalline structures.

In this research, scientists probed flakes of tellurene with thicknesses of less than 20 nanometers, using a technique called extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy. This work was carried out at beamline 20-BM of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility at DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory.

The EXAFS measurements characterized the structural changes in tellurene as flake thickness decreased, suggesting a transition from large-to-small polarons at a thickness of 10 nanometers. The experimental results gleaned from EXAFS, along with Raman spectroscopy data, were buttressed by theoretical insights and quantitative modeling that together provide a highly developed picture of polaron behavior as tellurene thickness varies.

These new findings will aid in developing the significant potential of tellurene for various technological applications, such as use in advanced transistors and sensing devices, and as a superconducting material. More broadly, these findings will also contribute to a deeper understanding of polaron behavior in other thin-film materials.

Tellurene is a thin-film semiconductor composed of helical chains of tellurium (Te) atoms. Because these helical chains interact through weak forces, it is sometimes referred to as a “quasi-one-dimensional” material. Tellurene is appealing for use in a variety of electronic applications due to its P-type semiconductor properties, which make it suitable for creating PN junctions when paired with N-type materials.

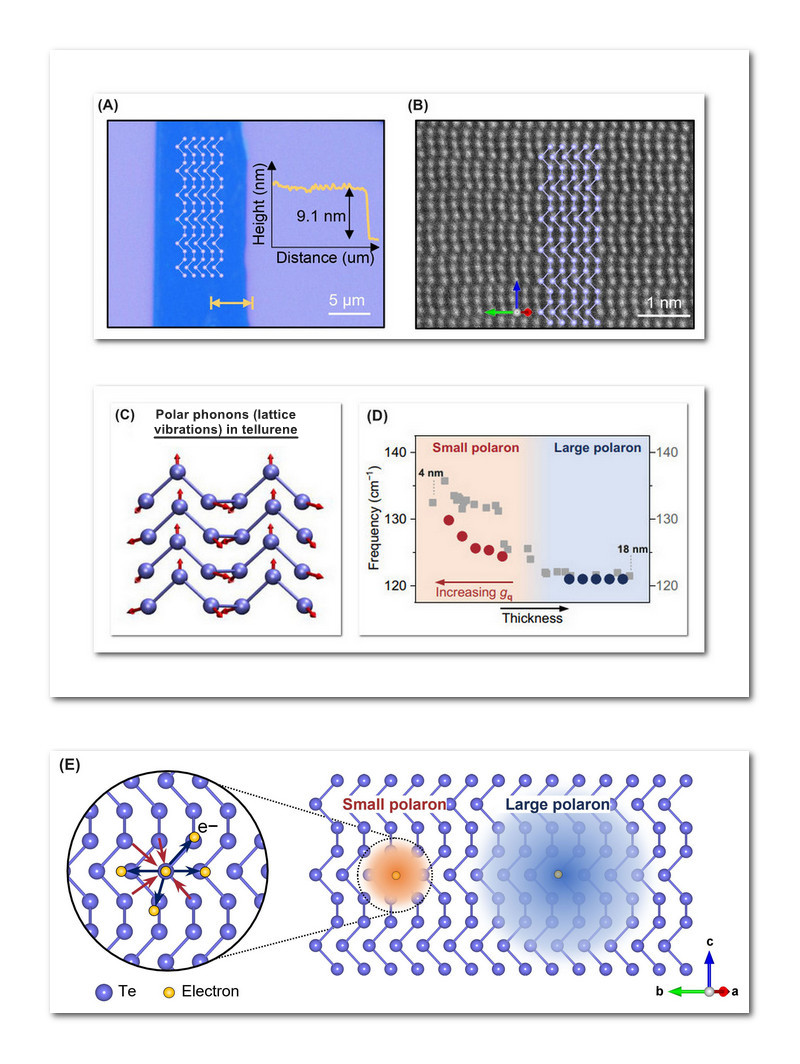

Tellurene samples were synthesized using a hydrothermal method that immerses the source materials in a closed bath of water-based solution subjected to high heat and pressure. Tellurium atoms subsequently precipitate out of the aqueous solution onto a substrate, forming tellurene flakes of varying thicknesses. Figure 1A shows a typical flake about 10 micrometers across and 9 nanometers thick. Fig. 1B is an electron microscope image of tellurene.

Phonons can exist in thin films as well as bulk 3D crystals. Just as a photon of light is a discrete unit (quantum) of electromagnetic energy, a phonon is the quantum of vibrational energy of a crystalline lattice. In tellurene, phonons can be polarized, meaning they vibrate along a particular direction, due to tellurene's crystalline structure (Fig. 1C).

When a phonon strongly interacts with an electron in a crystalline lattice, a quasiparticle called a polaron is formed. A quasiparticle is not an actual particle, like an atom or electron, but rather a collective excitation. However, since the interaction between an electron and phonon is quite complex, treating polarons as quasiparticles makes them easier to describe both mathematically and conceptually.

Tellurene flakes were probed with laser light in a technique called Raman spectroscopy, which was used to detect and characterize the polarons appearing in the flakes. The trend towards smaller polarons with decreasing flake thickness is plotted in Fig. 1D, which encompasses flake thicknesses from 18 down to 4 nm. Though small polarons are more spatially localized (Fig. 1E), they represent much stronger electron-phonon couplings. This greater coupling strength means that smaller polarons should exert a far greater influence on tellurene's phonon-dependent properties.

Decreases in both flake thickness and polaron size were correlated to reduced distances between the helical chains forming the tellurene flakes. These structural changes significantly altered several properties of the tellurene flakes as thicknesses decreased. For instance, electrical resistance in the flakes increased as polaron size decreased. The structural changes were captured by the EXAFS spectroscopy, which measured the distance between neighboring tellurium chains.

The observed large-to-small polaron transition, which involved increases in polaron polarity as well as structural and electronic changes to the tellurene flakes, were predicted to a good approximation through calculations performed by the research team. The strong agreement between simulation and experiment reinforces the researchers' confidence that their theoretical treatment of polaron behavior is robust.

These new theoretical and experimental insights will be crucial in the effort to control the magnitude and distribution of polarons in tellurene. Such control should eventually allow materials scientists to develop more efficient and tunable transistors, sensors, and (perhaps even) quantum devices based on this remarkable material. – Philip Koth

_______________________________________________________________________________________

See: K. Zhang1,2, C. Fu3, S. Kelly4, L. Liang5, S-H. Kang5, J. Jiang6, R. Zhang6, Y. Wang6, G. Wan2, P. Siriviboon3, M. Yoon5, P.D. Ye6, W. Wu6, M. Li3, S. Huang7, “Thickness-dependent polaron crossover in tellurene,” Sci. Adv. 11 eads4763 (Jan. 2025)

Author affiliations: 1Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; 2University of California Berkeley; 3Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 4Argonne National Laboratory; 5Oak Ridge National Laboratory; 6Purdue University; 7Rice University.

K.Z. and S.H. acknowledge the support from the National Science Foundation (NSF) (grant nos. ECCS-2246564, ECCS-1943895, ECCS-2230400, and DMR-2329111), Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) under grant FA9550-22-1-0408, and the Welch Foundation (award no. C-2144). C.F. acknowledges support from the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science (SC), Basic Energy Sciences (BES), award no. DE-SC0020148, while M.L. thanks support from the NSF Designing Materials to Revolutionize and Engineer our Future (DMREF) Program with award no. DMR-2118448. W.W. acknowledges support from AFOSR under award no. FA2386-21-1-4064. The synthesis of tellurene was supported by NSF under grant no. CMMI-2046936. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a US DOE Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory, and is based on research supported by the US DOE Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences, under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357. A portion of this research (DFT calculations) used resources at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, which is a US DOE Office of Science User Facility. This work was partly supported by the US DOE, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division (M.Y.) and by the US DOE, Office of Science, National Quantum Information Science Research Centers, Quantum Science Center (S.-H.K.). This research also used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported by the Office of Science of the US DOE under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231 and using NERSC award BES-ERCAP0024568. L.L. acknowledges computational resources of the Compute and Data Environment for Science (CADES) at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, which is supported by the Office of Science of the US DOE under contract no. DE-AC05-00OR22725.

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS at Argonne National Laboratory is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.