Many of the things we do, such as muscle contraction and firing of brain neurons, depend on our body’s ability to create small spikes of electrical discharge that make things happen. This is done, in part, through the ability of our cells to maintain different concentrations of potassium ions inside and outside the cell to create an electrochemical gradient across the cell membrane. In fact, 98% of the potassium ions in our body are inside our cells and only 2% are outside. Neurons use this gradient to generate electric currents by allowing potassium (K+) to rapidly flow down the gradient, causing, in turn, a voltage pulse to travel along their membranes.

These K+ ion currents are made possible by very fast and highly specific K+ ion channels. The structures of many of these channels have been solved and their conductance properties are quite well understood from membrane patch-clamping studies. However, the mechanisms of channel selectivity and ion flow at the atomic level have not been amenable to study until recently. Now, researchers have used electric-field-stimulated time resolved X-ray crystallography (EFX) to capture K+ ions hopping down the channel’s electrochemical gradient in real time. This work was conducted at the University of Chicago’s BioCARS (14-ID-B) and the Structural Biology Center (19-BM) at the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility at DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory.

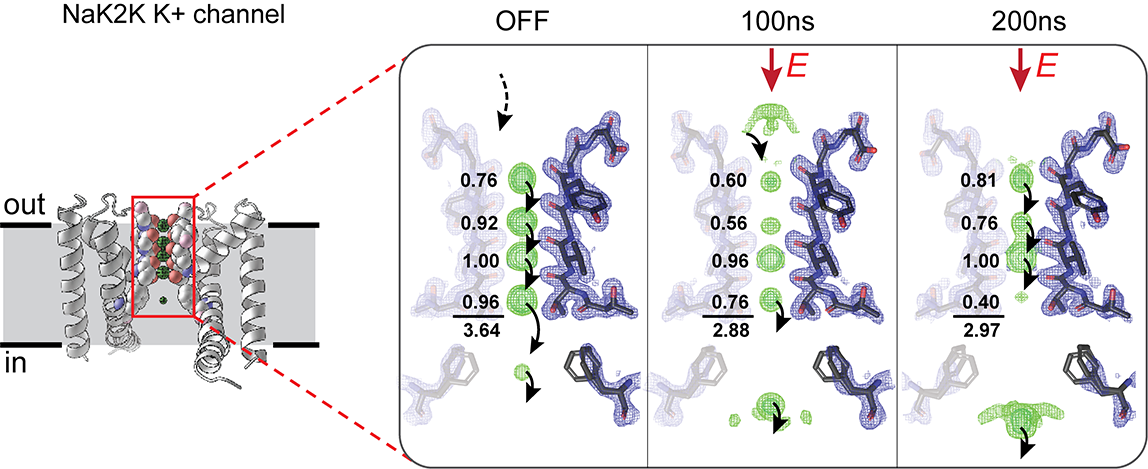

The research team, a group from Harvard University, Stanford University and the University of Chicago used EFX because it is well suited to the study of voltage-gated membrane channels. EFX allows researchers to apply an electric field at near-physiological levels to protein crystals to stimulate atomic motions and then pulse the crystals with brief intense X-ray pulses on a nanosecond timescale to capture protein structural changes at defined time delays. The group investigated how changes in transmembrane potential can influence protein function using a well-studied bacterial potassium channel called NaK2K.

Like other potassium channels, NaK2K is a transmembrane protein consisting of four helices that form the pore of the channel and orient amino acid side groups into the pore to catalyze the dehydration and flow of K+ ions through a tight selectivity filter (SF). The SF keeps other ions out while K+ ions hop between four binding sites (S1-S4) before being metered through a hydrophobic conduction gate. For the EFX experiments, the NaK2K crystals formed with pairs of molecules lined up in a head-to-head orientation, allowing investigators to observe molecules working in both directions in a single experiment.

The first step was to solve a high resolution (1.7 Å) room-temperature ground state structure for NaK2K. Analysis of the structure showed that all four of the binding sites in the SF were occupied by dehydrated K+ ions. Thallium replacement of the K+ ions to observe the sites more closely revealed that different sites had different affinities for K+ ions with S1 and S4 having lower affinities than sites S2 and S3. The structures also suggested that the conduction gate had two alternative conformations.

Once the electric field and the X-ray pulses were applied in the EFX experiment to create the time series, the team used the ground state as the basis for mapping changes over time. Similar to predictions from previous work by other researchers, the team observed that site occupancy in the SF was different depending on whether the flow of ions was inward or outward with respect to the physiological membrane orientation. Measurements of strain, a sensitive measure of local deformations that lead to broader conformational changes, indicated that the selectivity filter twists with a direction (clockwise or counterclockwise) determined by the direction of ion flow.

Interestingly, the atomic features of the channel that determine these dynamics are conserved in a wide variety of other potassium channels, suggesting they likely work by similar mechanisms. The findings from this study, the first to measure structural effects of transmembrane potential changes, suggest that the dynamics of the distinct inward and outward flows of the channel may result from the torque generated by movement of ions through the channel. – Judy Myers

See: B. Lee1,6, K.I. White2, M. Socolich1, M.A. Klureza3, R. Henning4, V. Srajer4, R. Ranganathan1,4, D.R. Hekstra5, “Direct visualization of electric-field-stimulated ion conduction in a potassium channel,” Cell 188, 1, 77-88.e15 (Jan. 2025).

Author affiliations: 1University of Chicago; 2Stanford University; 3Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Harvard University; 4Center for Advanced Radiation Sources, University of Chicago; 5Department of Molecular and Cell Biology and School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University; 6Merck and Co. Inc.

We thank J. Greisman and K. Dalton for their contributions to data collection and the design of the electrode system; members of the Ranganathan and Hekstra labs and all BioCARS facility scientists for help with data collection; Y. Jiang and Y.L. Lam for advice on purification and crystallization; and E. Perozo, B. Roux, and T.J. Lane for discussions. We also thank Dr. P. Anfinrud (NIH/NIDDK) for generous collaborative support of the BioCARS facility. Funding was provided by National Institute for General Medical Sciences grant RO1GM12345 (to R.R.); National Institute for General Medical Sciences grant RO1GM141697 (to R.R.); National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant P41GM118217 (to R.R.); Searle Scholarship Program grant SSP-2018-3240 (to D.R.H.); George W. Merck Fund of the New York Community Trust 338034 (to D.R.H.); Office of the NIH Director of the National Institutes of Health grant DP2OD028805 (to D.R.H.); U.S. DOE, Office of Basic Energy Sciences contract DE-AC02-06CH11357 (APS); U.S. DOE, Office of Basic Energy Sciences contract DE-AC02-76SF00515 (SSRL); and National Institute for General Medical Sciences grant P41GM103393 (SSRL).

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS at Argonne National Laboratory is one of the world’s most productive X-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.