Look at your hands. They are similar in shape and size, but you cannot orient one hand in any fashion to identically overlay it on the other. The creases of your palms will never face the same way at the same time your thumbs point in the same direction.

This inability to line up your hands exemplifies a fundamental aspect of the physical world called chirality. Two objects of opposite chirality appear the same as each other in a mirror, but no amount of geometrical manipulation will cause them to occupy the identical space and shape; you cannot superpose the objects. (Objects which can be superposed, such as spheres or construction nails, are achiral.) The quality of chirality imbues molecules with characteristics which achiral molecules lack, meaning that achiral crystals should not exhibit behavior that arises from chiral symmetry.

However, scientists have observed macroscopic characteristics previously only associated with chiral materials (specifically the circular photogalvanic effect) occurring within a transition metal previously considered achiral. Recent work by a team of international collaborators investigated 150-year-old scientific assumptions about symmetry and demonstrated how this particular material, the transition metal dichalcogenide titanium diselenide, produces a chiral charge density wave despite its apparently achiral lattice.

While you may have moved your hand randomly when trying to superpose it over the other hand, materials science categorizes the types of geometrical manipulation a crystal could undergo by whether said motion changes the spatial relationships between components such as atom spacing or charge density patterns. Symmetric changes preserve the existing spatial relationships. Translation is an example of a simple symmetric change; a more complex change would be rotating a crystal about an axis and then reflecting it in a plane perpendicular to the rotational axis.

Assessing the symmetry properties of a crystal involves understanding its existing arrangement of atoms and charge, as well as determining which geometrical changes to the crystal are symmetric. The crystalline form of titanium diselenide appears as hexagonal clusters of selenium ions aligned in a plane alternating with the titanium ions above and below. The mirror plane for the crystal bisects the selenium hexagons. Below its transition temperature of 200 Kelvin, a charge density wave is present in the crystal; this charge density wave has the potential to be chiral if the three-dimensional vector components are out of phase.

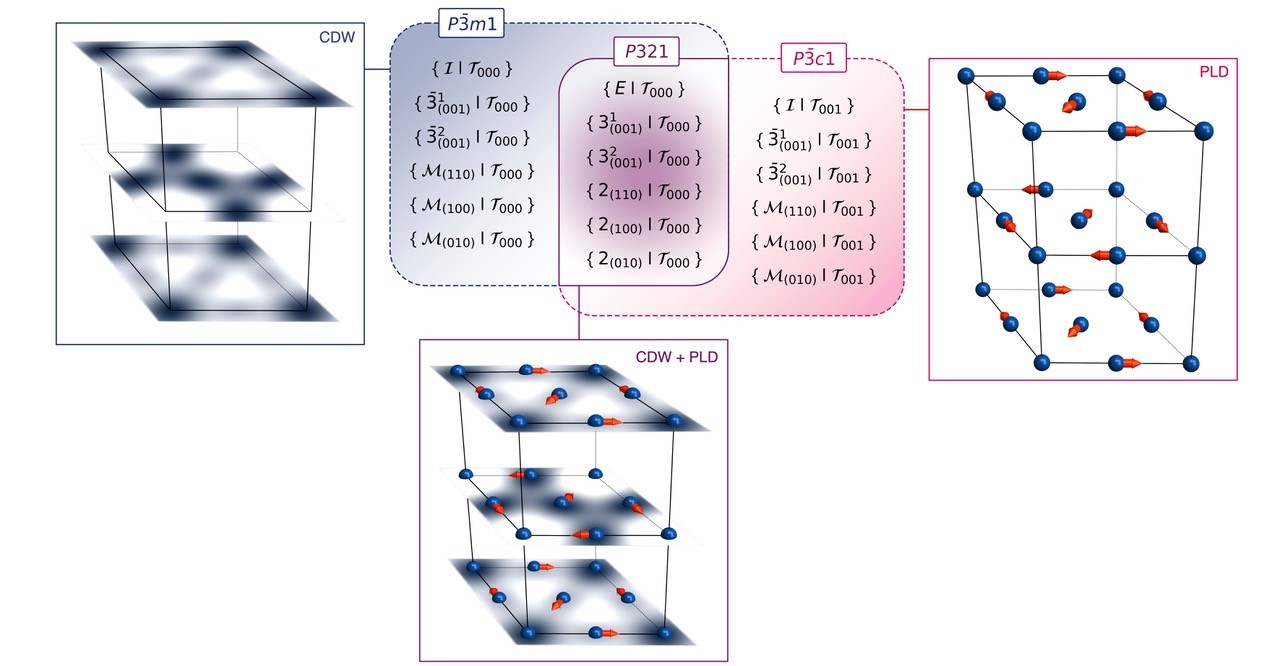

To analyze the symmetry properties of the lattice and charge modulations in titanium diselenide, the team began by re-assessing crystal configurations below and above the transition temperature. The team found that the charge modulations are symmetric across the mirror plane above and below the transition temperature. However, the lattice distortions in the presence of the charge density wave require translation to remain mirror images across the crystal's mirror plane. The team noted that it was rare to find that these two components were symmetric under different conditions.

The team performed further symmetry analysis on the crystalline form below the transition temperature, focusing on the transformation properties of charge density waves and periodic lattice distortion within the transition metal. This analysis showed that only six symmetry elements were preserved for both of these characteristics. Using Neumann's principle, which was coined in the 19th century and states that a crystal's macroscopic properties must include all of the types of symmetry evident in the crystal's lattice structure, the team concluded that the symmetry of the lattice must include only these same six symmetry elements. These six elements lack any symmetry elements which would make the crystal achiral, so the team further concluded that the crystal must be considered chiral.

One way to corroborate the chiral results of the symmetry assessment would be to confirm that only a single structural phase transition occurs in the titanium diselenide and that that transition occurs at a temperature of approximately 200 Kelvin. More specifically, the team would need to observe whether specific phonon modes of the material condensed at the same temperature as the structural transition. The team performed inelastic X-ray scattering using the 30-ID HERIX beamline at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) to characterize the material below its transition temperature. The APS is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility at DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory.

The research team found that the phonon modes in question did not condense. However, the phonon modes become highly temperature dependent as the temperature decreases, making the results of inelastic X-ray scattering challenging to interpret. The team also observed the behavior of the transition metal with Raman spectroscopy. By observing how the titanium diselenide scattered the incident beam, the team could determine which types of symmetry were no longer present as the temperature of the material changed.

After the scattering results eliminated many types of symmetry, the team concluded that only the most basic type of symmetry (the P1 space group) remained present in the titanium diselenide at the transition temperature. This most basic type of symmetry meets all the conditions in the quantum solids definition of chirality.

The team demonstrated that although neither the charge modulations nor the lattice distortions of the transition metal included chiral symmetries, these component's conflicting symmetries create a chiral charge density wave at the material's transition temperature. Their work also revealed an updated picture of the low-temperature structure of titanium diselenide. Lastly, the team's results demonstrated that the interplay between components influences symmetry in a way perhaps unaccounted for in the 19th century. – Mary Agner

See: K. Kim1, H-W. J. Kim1,2, S. Ha1, H. Kim1, J-K. Kim1, J. Kim1, J. Kwon1, J. Seol1, S. Jung3,4, C. Kim3,4, D. Ishikawa5, T. Manjo5, H. Fukui5, A.Q.R. Baron5, A. Alatas2, A. Said2, M. Merz6, M. Le Tacon6, J.M. Bok1, K-S. Kim1, B.J. Kim1, “Origin of the chiral charge density wave in transition-metal dichalcogenide,” Nat. Phys. 20 1919-1926 (2024)

Author affiliations: 1Pohang University of Science and Technology; 2Argonne National Laboratory; 3Institute for Basic Science; 4Seoul National Laboratory; 5Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute; 6Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

We thank J. van Wezel and A. Subedi for insightful discussions. This project is supported by IBS-R014-A2 and National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea through the SRC (grant no. 2018R1A5A6075964). The use of the Advanced Photon Source at the Argonne National Laboratory was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The additional synchrotron radiation experiments were performed at BL35XU of SPring-8 with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (proposal no. 2023B1728). C.K. acknowledges support by the Institute for Basic Science in Korea (grant nos. IBS-R009-G2, IBS-R009-D1) and a NRF of Korea grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (grant no. 2022R1A3B1077234). J.M.B. acknowledges support by the NRF of Korea (grant no. 2022R1C1C2008671). K.-S.K. is supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (grant no. RS-2024-00337134) of the NRF of Korea and by the TJ Park Science Fellowship of the POSCO TH Park Foundation.

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS at Argonne National Laboratory is one of the world’s most productive X-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness X-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other X-ray light source research facility. APS X-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.