Read the original press release by University College London here.

Additive manufacturing, also known as 3D printing, allows engineers to build mechanical parts with complex designs and fine details not easily achieved in other processes. There are challenges that need to be overcome, however, to use the technique in applications such as automobiles and aircraft, where the parts undergo strain or vibration.

In the 3D printing process, a highly focused laser beam scans rapidly across a bed of metallic powder to melt it, but tends to leave behind pores that weaken the material. Now scientists using the Advanced Photon Source (APS), a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility at DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory, have identified new pore formation mechanisms and shown that applying the right magnetic force can significantly reduce the problem.

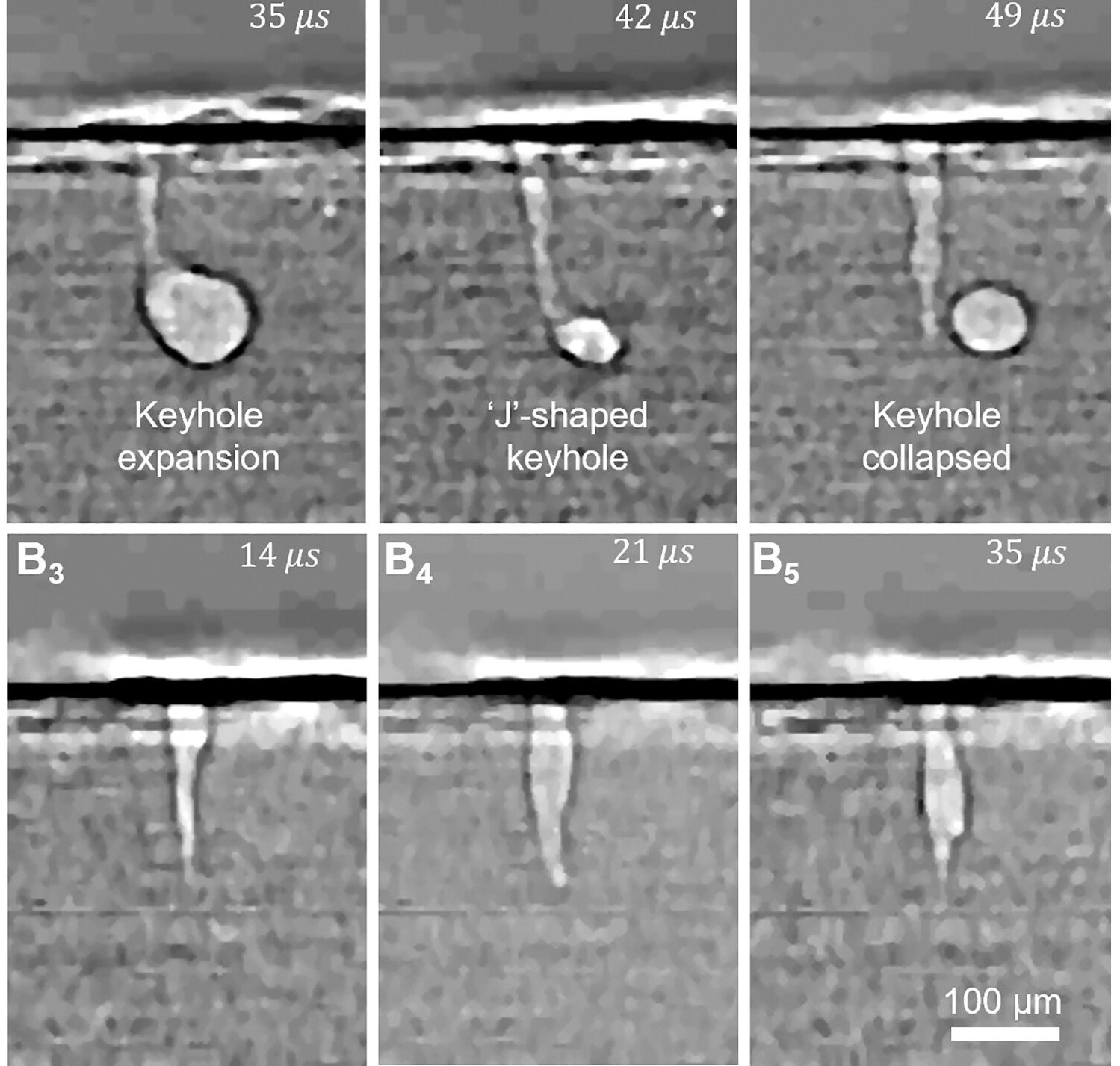

The pores arise from a process called keyhole instability. The laser used in the printing can have a power greater than 200 W, focused down to a spot approximately 50 µm in size that strikes the surface of the powder. The intense heating causes localized boiling, forming a metal vapor that pushes down into the powder to form a depression known as a keyhole. The keyhole is unstable. It oscillates at a rate faster than 1 ms and fluid flow on its back wall makes that side more vulnerable to fluctuations and collapse than the front.

As the laser scans across the powder bed at a rate of approximately 1 m/s, the fluctuations cause the keyhole to form into a “J” shape, and the lower protrusion of the “J” can break off and form a bubble, which becomes a pore in the final component. The fluid flow is normally dominated by Marangoni forces, in which liquid flows from low surface tension areas to high, minimizing the free energy. Surface tension depends on temperature and the laser scanning process causes huge thermal gradients, ranging from the alloy’s melting temperature to its evaporation temperature, about 3000°C for aluminum alloys.

The large temperature gradients also give rise to thermoelectric currents through the Seebeck effect, and applying a magnetic field activates both electromagnetic damping (EMD) and thermoelectric Lorentz forces, the second of which drives flow known as thermoelectric magnetohydrodynamics (TEMHD).

This study resolved a long-standing dispute over which mechanism, EMD or TEHMD, was responsible for stabilizing the keyhole. It turns out that, due to the small length scales of this additive manufacturing process, it was the TEMHD effect. The research team found that if the orientation of the magnetic field was perpendicular to the direction the laser was moving, the induced flow suppressed keyhole oscillations. Instead of a “J”, the keyhole took the shape of an “I” and did not pinch off into pores. Applying the magnetic field correctly reduced the number of pores by over 80%, and the remaining pores were smaller.

To watch the process in action, the researchers used beamline 32-ID of the APS, the only synchrotron X-ray source available with sufficient flux to take images on the time scales the team needed. To see the keyhole oscillation, which happens in under 1 ms, they had to capture images at over 100,000 frames per second. The team adapted a bespoke 3D printer at the beamline, in which they set up a sample bed that they could move rapidly under a laser. They filled it with a powder of AlSi10Mg, a lightweight alloy made up of aluminum, silicon, and magnesium.

Armed with what they learned, the researchers are now experimenting with pulsing the magnetic field to further perturb the flow. Their hope is that that will allow them to create finer grains within the material and hence achieve even better mechanical properties. – Neil Savage

_____________________________________________________________________________

See: X. Fan1,2, T.G. Fleming3, S.J. Clark4, K. Fezaa4, A.C.M. Getley1,2, S. Marussi1,2, H. Wang6, C.L.A. Leung1,2, A. Kao5, P.D. Lee1,2, “Magnetic modulation of keyhole instability during laser welding and additive manufacturing,” Science 387, 6736, 864-869 (Feb. 2025)

Author affiliations: 1University College London; 2Research Complex at Harwell; 3Queen’s University; 4Argonne National Laboratory; 5University of Greenwich; 6Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

All authors are grateful for the use of the facilities provided at APS and thank APS for providing the beamtime (GUP-73825) and staff in beamline ID32 for technical assistance. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source; a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. CLAL is funded by IPG Photonics/ Royal Academy of Engineering Senior Research Fellowship in SEARCH (ref: 525 RCSRF2324-18-71) and EP/W037483/1. HW acknowledges the financial supports of National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2024YFE0105700) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (52075327).

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS at Argonne National Laboratory is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.