Eutectic materials, naturally occurring composites of two or more crystals, are used in engine blocks, solder and 3D printing. Often, such applications involve heating the materials, which leads to changes in their microstructure that can affect their mechanical properties, such as strength. Using the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility at DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory, a team of researchers has learned how the microstructure evolves upon heating, which may allow them to change the synthesis of eutectics to improve those mechanical properties.

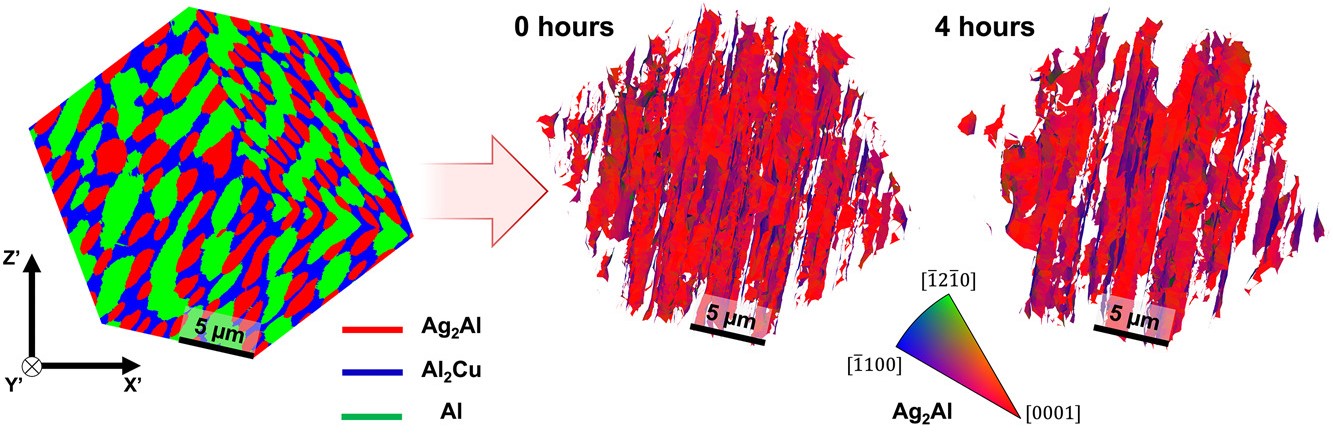

They studied a model silver-aluminum-copper alloy composed of three phases, one silver-rich, one aluminum-rich and one copper-rich. They heated the material to 773K and annealed it for four hours at that temperature. The material started out as three crystals that were interwoven in a structure resembling a ladder. When heated, the material tries to find its lowest energy state by lengthening the interfaces between the crystals. The microstructure coarsens, with some of the crystals becoming larger at the expense of others.

Much of the theory about eutectics is based on microstructures that have a small volume of one phase embedded in another. That theory predicts that the material would be self-similar, appearing identical at different size scales. In the model system, with three phases making up equal fractions of the volume, researchers were surprised to find no self-similarity. Instead, the microstructure evolved in part by coalescence. Rods of the silver-rich phase, for instance, would grow and become thicker until they touched each other, then they would merge into one rod. That evolution was irreversible. Such a change in the microstructure alters the mechanical properties of the material.

Additionally, the three phases did not coarsen independently of each other, but rather affected how the others evolved. When neighboring silver-aluminum rods coalesce, they pushed out the copper-rich channels that had existed between them. That is one reason for the lack of self-similarity in the evolving material.

Previous investigations of microstructure had involved looking at different samples annealed for different amounts of time, making it difficult to follow the evolution of the structure. This study, however, used transmission X-ray nanotomography, which allowed the researchers to follow changes as they occurred in the structure at nanoscale resolution and in three dimensions and in real time. They used APS beamline 32-ID. While transmission X-ray microscopy provided data on the three-dimensional structure, the team also used electron backscatter diffraction, which gave them information about the orientation of the crystals. Combining those measurements gave researchers a unified view of the structure.

Collecting the data at high temperatures made that data inherently noisy, so detecting the interfaces between different phases of the material was complicated. To address that, the team used a machine learning algorithm to discover the boundaries between the phases.

The researchers say their findings should be generalizable to other eutectic materials with equal proportions of solid phases. They do not yet know, however, how the evolution of the materials might occur if the microstructure were different at the beginning of process. The materials are synthesized starting with a liquid that self-organizes into the three phases and then solidifies. The researchers hope to manipulate the solidification pathways to achieve a different initial microstructure. They could then study that to see if it evolves differently during heating and what effect that has on the mechanical properties. The evolution of the structure and its associated properties can determine how long a material remains usable for a particular application. Learning how to manipulate microstructure and its evolution could provide ways to design materials that can withstand extreme environments, such as high temperatures. – Neil Savage

_____________________________________________________________________________

See: G.R. Lindemann1, P. Chao1, V. Nikitin2, V. De Andrade2, M. De Graef3, A.J. Shahani1,4, “Complexity and evolution of a three-phase eutectic coarsening uncovered by 4D nano-imaging,” Acta Materialia 266, 119684 (March 2024)

Author affiliations: 1Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of Michigan; 2Argonne National Laboratory; 3Carnegie Mellon University; 4Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Michigan

We thank the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under awards FA9550-18-1-0044 and FA9550-21-1-0260. We also thank Dr. Insung Han for his assistance in the acquisition of the TXM data. We thank the Michigan Center for Materials Characterization for use of the instruments and staff assistance. Marc De Graef would like to acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation (grant DMR-2203378) as well as the use of the computational resources of the Materials Characterization Facility at Carnegie Mellon University supported by grant MCF-677785. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory and is based on research supported by the U.S. DOE Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences , under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.Ionizing Radiation with Matter University Research Alliance (IIRM-URA) under Contract No. HDTRA1-20-2-0002. A.H. also acknowledges support from the U.S. National Science Foundation (ECCS No. 2015795). The content of the information does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the federal government, and no official endorsement should be inferred. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS at Argonne National Laboratory is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.