The original Oak Ridge National Laboratory press release by Dawn M. Levy can be read here.

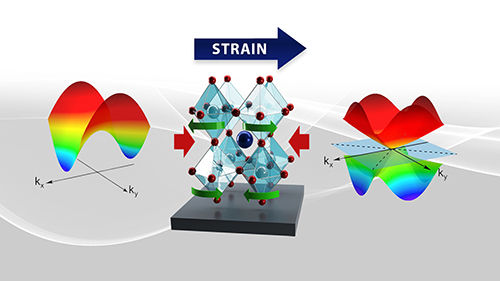

A team led by the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) has found a rare quantum material in which electrons move in coordinated ways, essentially “dancing.” Straining the material creates an electronic band structure that sets the stage for exotic, more tightly correlated behavior – akin to tangoing – among Dirac electrons, which are especially mobile electric charge carriers that may someday enable faster transistors. The results, which include studies carried out at the DOE’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Laboratory were published in the journal Science Advances.

“We combined correlation and topology in one system,” said co-principal investigator Jong Mok Ok, who conceived the study with principal investigator Ho Nyung Lee of ORNL. Topology probes properties that are preserved even when a geometric object undergoes deformation, such as when it is stretched or squeezed. “The research could prove indispensable for future information and computing technologies,” added Ok, a former ORNL postdoctoral fellow.

In conventional materials, electrons move predictably (for example, lethargically in insulators or energetically in metals). In quantum materials in which electrons strongly interact with each other, physical forces cause the electrons to behave in unexpected but correlated ways; one electron’s movement forces nearby electrons to respond.

To study this tight tango in topological quantum materials, Ok led the synthesis of an extremely stable crystalline thin film of a transition metal oxide. He and colleagues made the film using pulsed-laser epitaxy and strained it to compress the layers and stabilize a phase that does not exist in the bulk crystal. The scientists were the first to stabilize this phase.

Using theory-based simulations, co-principal investigator Narayan Mohanta, a former ORNL postdoctoral fellow, predicted the band structure of the strained material. “In the strained environment, the compound that we investigated, strontium niobate, a perovskite oxide, changes its structure, creating a special symmetry with a new electron band structure,” Mohanta said.

Different states of a quantum mechanical system are called “degenerate” if they have the same energy value upon measurement. Electrons are equally likely to fill each degenerate state. In this case, the special symmetry results in four states occurring in a single energy level.

“Because of the special symmetry, the degeneracy is protected,” Mohanta said. “The Dirac electron dispersion that we found here is new in a material.” He performed calculations with Satoshi Okamoto, who developed a model for discovering how crystal symmetry influences band structure.

“Think of a quantum material under a magnetic field as a 10-story building with residents on each floor,” Ok posited. “Each floor is a defined, quantized energy level. Increasing the field strength is akin to pulling a fire alarm that drives all the residents down to the ground floor to meet at a safe place. In reality, it drives all the Dirac electrons to a ground energy level called the extreme quantum limit.”

Lee added, “Confined here, the electrons crowd together. Their interactions increase dramatically, and their behavior becomes interconnected and complicated.” This correlated electron behavior, a departure from a single-particle picture, sets the stage for unexpected behavior, such as electron entanglement. In entanglement, a state Einstein called “spooky action at a distance,” multiple objects behave as one. It is key to realizing quantum computing.

“Our goal is to understand what will happen when electrons enter the extreme quantum limit, where we find phenomena we still don’t understand,” Lee said. “This is a mysterious area.”

Speedy Dirac electrons hold promise in materials including graphene, topological insulators and certain unconventional superconductors. ORNL’s unique material is a Dirac semimetal, in which electron valence and conduction bands cross and this topology yields surprising behavior. Ok led measurements of the Dirac semimetal’s strong electron correlations.

“We found the highest electron mobility in oxide-based systems,” Ok said. “This is the first oxide-based Dirac material reaching the extreme quantum limit.”

That bodes well for advanced electronics. Theory predicts that it should take about 100,000 tesla (a unit of magnetic measurement) for electrons in conventional semiconductors to reach the extreme quantum limit. The researchers took their strain-engineered topological quantum material to Eun Sang Choi of the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory at the University of Florida to see what it would take to drive electrons to the extreme quantum limit. There, he measured quantum oscillations showing the material would require only 3 tesla to achieve that.

Other specialized facilities allowed the scientists to experimentally confirm the behavior Mohanta predicted. The experiments occurred at low temperatures so that electrons could move around without getting bumped by atomic-lattice vibrations.

Jeremy Levy’s group at the University of Pittsburgh and the Pittsburgh Quantum Institute confirmed quantum transport properties.

With synchrotron x-ray diffraction carried out at the X-ray Science Division Surface Scattering & Microdiffraction (SSM) Group’s 33-ID-D x-ray beamline at the APS, Hua Zhou of the SSM Group confirmed that the material’s crystallographic structure stabilized in the thin film phase yielded the unique Dirac band structure.

Sangmoon Yoon and Andrew Lupini, both of ORNL, conducted scanning transmission electron microscopy experiments at ORNL that showed that the epitaxially grown thin films had sharp interfaces between layers and that the transport behaviors were intrinsic to strained strontium niobate.

“Until now, we could not fully explore the physics of the extreme quantum limit due to the difficulties in pushing all electrons to one energy level to see what would happen,” Lee said. “Now, we can push all the electrons to this extreme quantum limit by applying only a few tesla of magnetic field in a lab, accelerating our understanding of quantum entanglement.”

See: Jong Mok Ok1‡, Narayan Mohanta1, Jie Zhang1, Sangmoon Yoon1, Satoshi Okamoto1, Eun Sang Choi2, Hua Zhou3, Megan Briggeman4, 5, Patrick Irvin4, 5, Andrew R. Lupini1, Yun-Yi Pai1, Elizabeth Skoropata1, Changhee Sohn1, Haoxiang Li1, Hu Miao1, Benjamin Lawrie1, Woo Seok Choi6, Gyula Eres1, Jeremy Levy4, 5, and Ho Nyung Lee1*, “Correlated oxide Dirac semimetal in the extreme quantum limit,” Sci. Adv. 7, eabf9631 (15 September 2021). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abf9631

Author affiliations: 1Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 2National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, 3Argonne National Laboratory, 4University of Pittsburgh, 5Pittsburgh Quantum Institute, 6Sungkyunkwan University ‡Present address: Pusan National University

Correspondence: * hnlee@ornl.gov

This work was supported by the U.S. DOE Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, and in part by the Computational Materials Sciences Program. The high-magnetic field measurements were performed at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, which is supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) cooperative agreement no. DMR-1644779 and the state of Florida. Extraordinary facility operations were supported, in part, by the DOE Office of Science through the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a consortium of DOE national laboratories focused on the response to COVID-19, with funding provided by the Coronavirus CARES Act. W.S.C. was supported by Basic Science Research Programs through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (NRF-2021R1A2C2011340). J.L. acknowledges support from NSF (PHY-1913034) and Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship (N00014-15-1-2847). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

UT-Battelle manages ORNL for the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States. The Office of Science is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.