The original Cornell [University] Chronicle story by David Nutt can be read here.

Some imperfections pay big dividends. A Cornell University-led collaboration used x-ray nanoimaging at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) to gain an unprecedented view into solid-state electrolytes, revealing previously undetected crystal defects and dislocations that may now be leveraged to create superior energy storage materials. The group’s paper was published in the journal Nano Letters.

For a half-century, materials scientists have been investigating the effects of tiny defects in metals. The evolution of imaging tools has now created opportunities for exploring similar phenomena in other materials, most notably those used for energy storage.

A group led by Andrej Singer, assistant professor and David Croll Sesquicentennial Faculty Fellow in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Cornell, uses synchrotron radiation to uncover atomic-scale defects in battery materials that conventional approaches, such as electron microscopy, have failed to find.

The Singer Group is particularly interested in solid-state electrolytes because they could potentially be used to replace the liquid and polymer electrolytes in lithium-ion batteries. One of the major drawbacks of liquid electrolytes is they are susceptible to the formation of spiky dendrites between the anode and cathode, which short out the battery or, even worse, cause it to explode.

Solid-state electrolytes have the virtue of not being flammable, but they present challenges of their own. They don’t conduct lithium ions as strongly or quickly as fluids and maintaining contact between the anode and cathode can be difficult. Solid-state electrolytes also need to be extremely thin; otherwise, the battery would be too bulky and any gain in capacity would be negated.

What is the one thing that could make solid-state electrolytes viable? Tiny defects, Singer said.

“These defects might facilitate ionic diffusion, so they might allow the ions to go faster. That’s something that’s known to happen in metals,” he said. “Also like in metals, having defects is better in terms of preventing fracture. So, they might make the material less prone to breaking.”

Singer’s group collaborated with Nikolaos Bouklas, assistant professor in the Cornell Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering and a co-author of the paper, who helped them understand how defects and dislocations might impact the mechanical properties of solid-state electrolytes.

The Cornell team then partnered with researchers at Virginia Tech – led by Feng Lin, the paper’s co-senior author – who synthesized the sample: a garnet crystal structure, lithium lanthanum zirconium oxide (LLZO), with various concentrations of aluminum added in a process called doping.

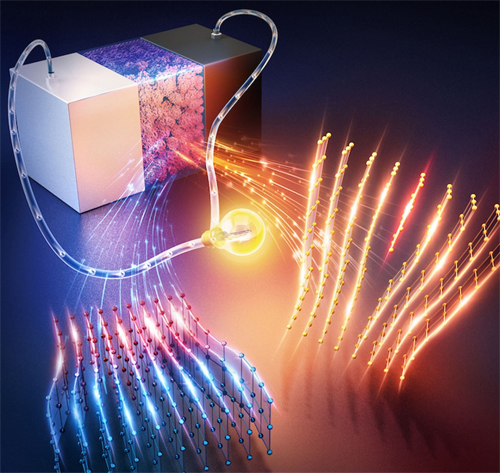

Using the X-ray Science Division Microscopy Group’s 34-ID-C x-ray beamline at the APS (an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory), they and a colleague from the APS employed the Bragg coherent diffractive imaging technique in which a pure, collimated x-ray beam is focused on a single micron-sized grain of LLZO. Electrolytes consist of millions of these grains. The beam created a three-dimensional (3-D) image that ultimately revealed the material’s morphology and atomic displacements.

“These electrolytes were assumed to be perfect crystals,” Sun said. “But what we find are defects such as dislocations and grain boundaries that haven’t been reported before. Without our 3-D imaging, which is extremely sensitive to defects, it would be likely impossible to see those dislocations because the dislocation density is so low.”

The researchers now plan to conduct a study that measures how the defects impact the performance of solid-state electrolytes in an actual battery.

“Now that we know exactly what we’re looking for, we want to find these defects and look at them as we operate the battery,” Singer said. “We are still far away from it, but we may be at the beginning of a new development where we can design these defects on purpose to make better energy storage materials.”

See: Yifei Sun1, Oleg Gorobstov1, Linqin Mu2, Daniel Weinstock1, Ryan Bouck1, Wonsuk Cha3, Nikolaos Bouklas1, Feng Lin2*, and Andrej Singer1**, “X‑ray Nanoimaging of Crystal Defects in Single Grains of Solid-State Electrolyte Li7−3xAlxLa3Zr2O12,” Nano Lett. Published on-line April 29. 2021. DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c00315

Author affiliations: 1Cornell University, 2Virginia Tech, 3Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: *fenglin@vt.edu, **asinger@cornell.edu

The work at Cornell was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grand No. (CAREER DMR 1944907). The work at Virginia Tech was supported by the NSF (Grant no. DMR 1832613). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility, operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02- 06CH11357.

Copyright © Cornell Chronicle

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.