Physicists have demonstrated that noble metals are not as structurally stable, as previously believed. Following up on earlier work on gold, Washington State University (WSU) researchers using high-brightness x-rays at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) showed that high-pressure shock waves can also change the crystal structure of silver. These results, published in Physical Review Letters, are important for our understanding of the material properties and response of these useful metals, which are often valued for their stability under pressure.

Studying the effect of pressure on materials can provide fundamental insights into their physical and chemical properties, but there are different types of pressure. Under static pressure, materials experience a steady, uniform compression with little shear strain. But shock waves produce a sudden compression that results in significant shear strain and rapid microstructural changes.

Nobel metals are considered extremely stable under pressure, as they show great structural stability under static compression. However, work in 2019 by researchers at WSU and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory showed that this is not the case with shock compression. Both groups found that under shock induced pressures of around 150 gigapascals (GPa), gold changes from its normal atomic arrangement, known as face-centered-cubic, to a different crystal structure, body-centered-cubic.

WSU researchers have also reported that shock-compressed gold developed numerous stacking faults. These are lattice defects in the highly ordered, repeating layers of atoms that form crystals. Stacking faults occur when one atomic layer is shifted relative to another, breaking the symmetry of the crystal.

The WSU researchers wondered if the stacking faults played a role in the change of gold’s crystal structure. To examine this linkage further, in their latest research they explored the effect of shock compression on two other noble metals: silver and platinum. These materials were chosen because the researchers expected silver to develop significant stacking faults under shock compression, but platinum to experience few.

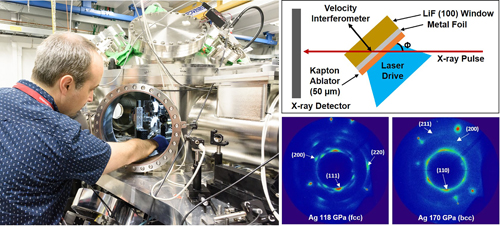

The work was carried out at the Dynamic Compression Sector beamline 35-ID at the APS, an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory. The researchers used laser pulses to vaporize an aluminized plastic film. This created shock waves that travelled through sheets of silver or platinum foil. By varying the laser pulse shapes and energies the team was able to generate shock stresses in these metals with pressures ranging from 33 GPa to 383 GPa.

The effects of the shock waves were measured using x-ray diffraction. High-energy, 100-picosecond duration x-ray pulses enabled the researchers to capture real-time observations while the shock waves were propagating through the samples, rather than before and after shots. In fact, single x-ray diffraction measurements of the metals showed the material in two different states: unshocked and at peak shock.

As expected, the shock waves induced stacking faults in silver, which increased rapidly in number with pressure. At pressures between 144 GPa to 158 GPa, the crystal structure began to transform from face-centered-cubic to body-centered-cubic. By about 170 GPa the measurements suggested that the entire crystal structure of the silver was body-centered-cubic. At pressures of around 197 GPa the metal became molten.

Platinum behaved differently. The metal maintained its face-centered-cubic structure at pressures up to about 380 GPa, and then began to melt. This suggests that shock compression does not change the crystalline structure of platinum, as it does for silver and gold. X-ray data also suggested that platinum did not have stacking faults at pressures up to around 339 GPa. Beyond this, the researcher say that it may have developed a small number of such faults.

These results, and those for gold, show that not all noble metals are as structurally stable as previously thought. According to the researchers, they suggest that high-pressure shock compression can induce stacking faults in these materials, which in turn promote structural transformations that do not occur under static compression.

This could have important implications for our understanding of these metals, particularly in applications where their compression response and structural stability are important. Gold is currently used as a pressure calibrant in diamond anvil cell experiments, for example, but these findings suggest that platinum may be a better choice.

More work is now needed to better understand the specific mechanisms responsible for the transitions from face-centered-cubic to body-centered-cubic crystal structures in noble metals under shock compression. ― Michael Allen

See: Surinder M. Sharma, Stefan J. Turneaure, J. M. Winey, and Y. M. Gupta*, “What Determines the fcc-bcc Structural Transformation in Shock Compressed Noble Metals?,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 235701 (2020). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.235701

Author affiliation: Washington State University

Correspondence: * ymgupta@wsu.edu

Pinaki Das, Kory Green, Ray Gunawidjaja, Yuelin Li, Korey Mercer, Drew Rickerson, Paulo Rigg, Adam Schuman, Nick Sinclair, Xiaoming Wang, Brendan Williams, Jun Zhang, and Robert Zill at the Dynamic Compression Sector are gratefully acknowledged for their expert assistance with the experiments. This work was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy (DOE), National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) under Award No. DE-NA0002007. The Dynamic Compression Sector is operated by Washington State University under DOE/NNSA Award No. DE-NA0002442. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.