The original Georgia Institute of Technology news release by John Toon can be read here.

Using x-ray tomography at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), a research team has observed the internal evolution of the materials inside solid-state lithium batteries as they were charged and discharged. Detailed three-dimensional information from the research could help improve the reliability and performance of the batteries, which use solid materials to replace the flammable liquid electrolytes in existing lithium-ion batteries. The research, supported by the National Science Foundation, a Sloan Research Fellowship, and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, was reported in the journal Nature Materials.

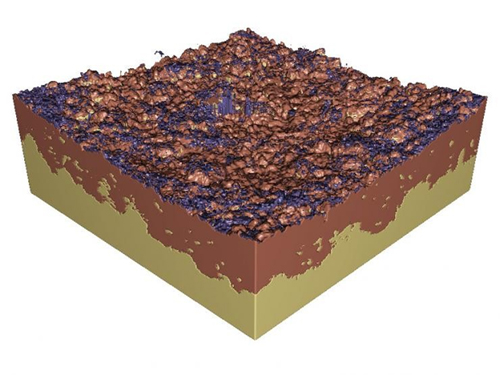

The operando synchrotron x-ray computed microtomography imaging revealed how the dynamic changes of electrode materials at lithium/solid-electrolyte interfaces determine the behavior of solid-state batteries. The researchers from Georgia Tech, collaborating with others from Purdue University and the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (Republic of Korea), found that battery operation caused voids to form at the interface, which created a loss of contact that was the primary cause of failure in the cells.

"This work provides fundamental understanding of what is happening inside the battery, and that information should be important for guiding engineering efforts that will push these batteries closer to commercial reality in the next several years," said Matthew McDowell, an assistant professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and the School of Materials Science and Engineering at Georgia Tech. "We were able to understand exactly how and where voids form at the interface, and then relate that to battery performance."

The lithium-ion batteries now in widespread use for everything from mobile electronics to electric vehicles rely on a liquid electrolyte to carry ions back and forth between electrodes within the battery during charge and discharge cycles. The liquid uniformly coats the electrodes, allowing free movement of the ions.

Rapidly evolving solid-state battery technology instead uses a solid electrolyte, which should help boost energy density and improve the safety of future batteries. But removal of lithium from electrodes can create voids at interfaces that cause reliability issues that limit how long the batteries can operate.

"To counter this, you could imagine creating structured interfaces through different deposition processes to try to maintain contact through the cycling process," McDowell said. "Careful control and engineering of these interface structures will be very important for future solid-state battery development, and what we learned here could help us design interfaces."

The Georgia Tech research team, led by first author and graduate student Jack Lewis, built special test cells about 2 millimeters wide, which were designed to be studied at the APS, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory. Four members of the team, with colleagues from the APS, studied the changes in battery structure during a five-day period of intensive experiments at the Argonne X-ray Science Division Imaging Group’s 2-BM x-ray beamline at the APS.

"The instrument takes images from different directions, and you reconstruct them using computer algorithms to provide 3-D images of the batteries over time," McDowell said. "We did this imaging while we were charging and discharging the batteries to visualize how things were changing inside the batteries as they operated."

Because lithium is so light, imaging it with X-rays can be challenging and required a special design of the test battery cells. The technology used at Argonne is similar to what is used for medical computed tomography scans. "Instead of imaging people, we were imaging batteries," he said.

Because of limitations in the testing, the researchers were only able to observe the structure of the batteries through a single cycle. In future work, McDowell would like to see what happens over additional cycles, and whether the structure somehow adapts to the creation and filling of voids. The researchers believe the results would likely apply to other electrolyte formulations, and that the characterization technique could be used to obtain information about other battery processes.

Battery packs for electric vehicles must withstand at least a thousand cycles during a projected 150,000-mile lifetime. While solid-state batteries with lithium metal electrodes can offer more energy for a given size battery, that advantage won't overcome existing technology unless they can provide comparable lifetimes.

"We are very excited about the technological prospects for solid-state batteries," McDowell said. "There is substantial commercial and scientific interest in this area, and information from this study should help advance this technology toward broad commercial applications."

See: John A. Lewis1, Francisco Javier Quintero Cortes1, Yuhgene Liu1, John C. Miers1, Ankit Verma2, Bairav S. Vishnugopi2, Jared Tippens1, Dhruv Prakash1, Thomas S. Marchese1, Sang Yun Han1, Chanhee Lee1, 3, Pralav P. Shetty1, Hyun-Wook Lee3, Pavel Shevchenko4, Francesco De Carlo4, Christopher Saldana1, Partha P. Mukherjee2, and Matthew T. McDowell1*, “Linking void and interphase evolution to electrochemistry in solid-state batteries using operando X-ray tomography,” Nat. Mater., published on line 28 January 2021. DOI: 10.1038/s41563-020-00903-2

Author affiliations: 1Georgia Institute of Technology, 2Purdue University, 3Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, 4Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: * mattmcdowell@gatech.edu

This work is partially supported by the National Science Foundation under Award No. DMR-1652471, a Sloan Research Fellowship in Chemistry, a NASA Space Technology grant, the Colciencias-Fulbright scholarship program cohort 2016, the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy/Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (MOTIE/KETEP) (20194010000100), the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) under Grant FA9550-17-1-0130, and the Scialog program sponsored jointly by Research Corporation for Science Advancement and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation that includes a grant to Purdue University by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

© 2021 Georgia Institute of Technology

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.