The original Fred Hutch News Service by Sabin Russell can be read here.

Scientists at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle led a team that employed high-brightness x-rays from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) to show that a potent antibody from a COVID-19 survivor interferes with a key feature on the surface of the coronavirus’s distinctive spikes and induces critical pieces of those spikes to break off in the process.

The antibody — a tiny, Y-shaped protein that is one of the body’s premier weapons against pathogens including viruses — was isolated by the Fred Hutch team from a blood sample received from a Washington state patient in the early days of the pandemic.

The team led by Leo Stamatatos, Andrew McGuire, and Marie Pancera previously reported that, among dozens of different antibodies generated naturally by the patient, this one — dubbed CV30 — was 530 times more potent than any of its competitors.

Using tools derived from high-energy physics, Hutch structural biologist Pancera and her postdoctoral fellow Nicholas Hurlburt have now mapped the molecular structure of CV30. They and their colleagues published their results online in the journal Nature Communications. The research team in this study included colleagues from the Emory University School of Medicine and the University of Washington.

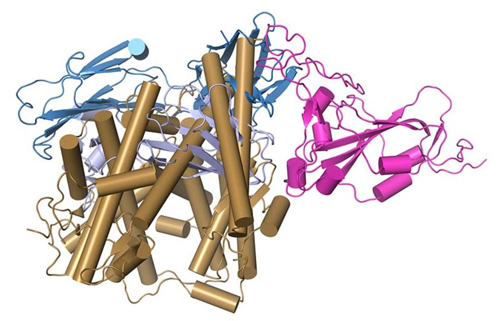

The product of their research is a set of computer-generated 3D images that look to the untrained eye as an unruly mass of noodles. But to scientists they show the precise shapes of proteins comprising critical surface structures of antibodies, the coronavirus spike and the spike’s binding site on human cells. The models depict how these structures can fit together like pieces of a 3D puzzle (Fig. 1).

“Our study shows that this antibody neutralizes the virus with two mechanisms. One is that it overlaps the virus’s target site on human cells, the other is that it induces shedding or dissociation of part of the spike from the rest,” Pancera said.

On the surface of the complex structure of the antibody is a spot on the tips of each of its floppy, Y-shaped arms. This infinitesimally small patch of molecules can neatly stretch across a spot on the coronavirus spike, a site that otherwise works like a grappling hook to grab onto a docking site on human cells.

The target for those hooks is the ACE2 receptor, a protein found on the surfaces of cells that line human lung tissues and blood vessels. But if CV30 antibodies cover those hooks, the coronavirus cannot dock easily with the ACE2 receptor. Its ability to infect cells is blunted.

This very effective antibody not only jams the business end of the coronavirus spike, it apparently causes a section of that spike, known as S1, to shear off. Hutch researcher McGuire and his laboratory team performed an experiment showing that, in the presence of this antibody, there is reduction of antibody binding over time, suggesting the S1 section was shed from the spike surface.

The S1 protein plays a crucial role in helping the coronavirus to enter cells. Research indicates that after the spike makes initial contact with the ACE2 receptor, the S1 protein swings like a gate to help the virus fuse with the captured cell surface and slip inside. Once within a cell, the virus hijacks components of its gene and protein-making machinery to make multiple copies of itself that are ultimately released to infect other target cells.

The incredibly small size of antibodies is difficult to comprehend. These proteins are so small they would appear to swarm like mosquitos around a virus whose structure can only be seen using the most powerful of microscopes. The tiny molecular features Pancera’s team focused on the tips of the antibody protein are measured in nanometers — billionths of a meter.

Yet structural biologists equipped with the right tools can now build accurate 3D images of these proteins, deduce how parts of these structures fit like puzzle pieces, and even animate their interactions.

Key to building models of these nanoscale proteins is the use of x-ray crystallography. Structural biologists determine the shapes of proteins by illuminating frozen, crystalized samples of these molecules with extremely powerful x-rays. The most powerful x-rays come from a gigantic instrument known as a synchrotron light source. Born from atom-smashing experiments dating back to the 1930s, a synchrotron is a ring of massively powerful magnets that are used to accelerate a stream of electrons around a circular track at close to the speed of light. Synchrotrons are so costly that only governments can build and operate them. There are only 40 of them in the world.

Pancera’s work used the Structural Biology Center‘s (SBC-XSD’s) 19-ID x-ray beamline at the APS, an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory, to determine the structure of CV30.

The Fred Hutch team’s work on CV30 builds on that of other structural biologists who are studying a growing family of potent neutralizing antibodies against the coronavirus. The goal of most coronavirus vaccine candidates is to stimulate and train the immune system to make similar neutralizing antibodies, which can recognize the virus as an invader and stop COVID-19 infections before they can take hold.

Neutralizing antibodies from the blood of recovered COVID-19 patients may also be infused into infected patients — an experimental approach known as convalescent plasma therapy. The donated plasma contains a wide variety of different antibodies of varying potency. Although once thought promising, recent studies have cast doubt on its effectiveness.

However, pharmaceutical companies are experimenting with combinations of potent neutralizing antibodies that can be grown in a laboratory. These “monoclonal antibody cocktails” can be produced at industrial scale for delivery by infusion to infected patients or given as prophylactic drugs to prevent infection.

The Fred Hutch research team holds out hope that the protein they discovered, CV30, may prove to be useful in the prevention or treatment of COVID-19. To find out, this antibody, along with other candidate proteins their team is studying, need to be tested pre-clinically and then in human trials.

“It is too early to tell how good they might be,” Pancera said.

See: Nicholas K. Hurlburt1, Emilie Seydoux1, Yu-Hsin Wan1, Venkata Viswanadh Edara2, Andrew B. Stuart1, Junli Feng1, Mehul S. Suthar2, Andrew T. McGuire1,3, Leonidas Stamatatos1, 3, and Marie Pancera1, 4*, “Structural basis for potent neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 and role of antibody affinity maturation,” Nat. Commun. 11, 5413 (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-19231-9

Author affiliations: 1Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 2Emory University School of Medicine, 3University of Washington, 4National Institute of Health

Correspondence: *mpancera@fredhutch.org

SBC-XSD is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Biological and Environmental Research under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. The SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assay efforts were in part supported by the Emory EVPHA Synergy Fund award, Center for Childhood Infections and Vaccines, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, COVID-Catalyst-I3 Funds from the Woodruff Health Sciences Center and Emory School of Medicine. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Extraordinary facility operations were supported in part by the DOE Office of Science through the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a consortium of DOE national laboratories focused on response to COVID-19, with funding provided by the Coronavirus CARES Act.

The U.S. Department of Energy's APS is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.