The original University of Illinois Press release by Lois Yoksoulian can be read here.

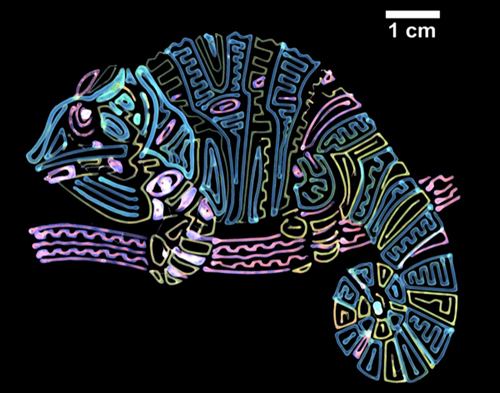

Brilliantly colored chameleons, butterflies, opals – and now some three-dimensional (3-D)-printed materials – reflect color by using nanoscale structures called photonic crystals. A new study in part carried out at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) demonstrates how a modified 3-D printing process provides a versatile approach to producing multiple colors from a single ink. The study is published in the journal Science Advances.

Some of the most vibrant colors in nature come from a nanoscale phenomenon called structural coloration. When light rays reflect off these periodically placed structures located in the wings and skins of some animals and within some minerals, they constructively interfere with each other to amplify certain wavelengths and suppress others. When the structures are well ordered and small enough – about a thousand times smaller than a human hair, the researchers said – the rays produce a vivid burst of color.

“It is challenging to reproduce these vibrant colors in the polymers used to produce items like environmentally friendly paints and highly selective optical filters,” said study leader Ying Diao, a chemical and biomolecular engineering professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “Precise control of polymer synthesis and processing is needed to form the incredibly thin, ordered layers that produce the structural color as we see in nature.”

The study, which included small-angle X-ray scattering experiments carried out in collaboration with Byeongdu Lee at the X-ray Science Division 12-ID-B beamline at the APS, reports that by carefully tuning the assembly process of uniquely structured bottlebrush-shaped polymers during 3-D printing, it is possible to print photonic crystals with tunable layer thicknesses that reflect the visible light spectrum from a single ink.

The ink contains branched polymers with two bonded, chemically distinct segments. The researchers dissolve the material into a solution that mixes the polymer chains just before printing. After printing and as the solution dries, the components separate at a microscopic scale, forming nanoscale layers that exhibit different physical properties depending on the speed of assembly.

“The biggest challenge of the polymer synthesis is combining the precision required for the nanoscale assembly with the production of the large amounts of material necessary for the 3D-printing process,” said co-author Damien Guironnet, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering.

In the lab, the team uses a modified consumer 3D printer to fine-tune how fast a printing nozzle moves across a temperature-controlled surface. “Having control over the speed and temperature of ink deposition allows us to control the speed of assembly and the internal layer thickness at the nanoscale, which a normal 3D printer cannot do,” said Bijal Patel, a graduate student and lead author of the study. “That dictates how light will reflect off of them and, therefore, the color we see.”

The researchers said the color spectrum they have achieved with this method is limited, but they are working to make improvements by learning more about the kinetics behind how the multiple layers form in this process.

Additionally, the team is working on expanding the industrial relevance of the process, as the current method is not well suited for large-volume printing. “We are working with the Damien Guironnet, Charles Sing and Simon Rogers groups at the U. of I. to develop polymers and printing processes that are easier to control, bringing us closer to matching the vibrant colors produced by nature,” Diao said.

“This work highlights what is achievable as researchers begin to move past focusing on 3D printing as just a way to put down a bulk material in interesting shapes,” Patel said. “Here, we are directly changing the physical properties of the material at the point of printing and unlocking new behavior.”

See: Bijal B. Patel1, Dylan J. Walsh1, Do Hoon Kim2, Justin Kwok1, Byeongdu Lee3, Damien Guironnet1, and Ying Diao1*, “Tunable structural color of bottlebrush block copolymers through direct-write 3D printing from solution,” Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz7202 (10 June 2020). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz7202

Author affiliations: 1University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2University of Michigan, 3Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: *yingdiao@illinois.edu

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under DMREF award no. DMR-1727605. J.K. and Y.D. acknowledge partial support by the NSF CAREER award under grant no. NSF DMR 18-47828. Major funding for the 500-MHz Bruker CryoProbe was provided by the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust to the University of Illinois School of Chemical Sciences NMR Lab. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by the Argonne National Laboratory under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.