As we know all too well, a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome-like coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) recently emerged and rapidly spread among humans. A key to tackling this pandemic is to learn how the virus attaches to receptors on human cells. This mechanism would likely explain the levels of SARS-CoV-2 infectivity, how it jumped to humans from an animal host, and host range. SARS-CoV-2 and its close coronavirus relative, SARS-CoV, recognize the same receptor in humans called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (hACE-2). Researchers using the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory have determined the crystal structure of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 — engineered to facilitate crystallization — in complex with ACE2. In comparison with the SARS-CoV RBD, an ACE2-binding site in SARS-CoV-2, RBD has a more compact, stable conformation. These structural features of SARS-CoV-2 RBD increase the likelihood of the coronavirus binding to hACE-2. Additionally, the researchers show that RaTG13, a bat coronavirus that is closely related to SARS-CoV-2, also uses hACE-2 as its receptor. The differences among SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV and RaTG13 in hACE-2 recognition shed light on the potential animal-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2. This study provides guidance for intervention strategies that target receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2.

The recent emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in China has caused hundreds of thousands of deaths and overwhelmed health care systems around the globe. Following other notable recent coronavirus outbreaks, including SARS-CoV in 2002 and MERS-CoV in 2012, SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh coronavirus known to cause human disease.

Coronaviruses are a group of large, enveloped viruses with single-stranded RNA genomes. All coronaviruses share a similar means of infection: When the virus encounters a human cell, spike-shaped proteins on its surface attach to cell receptors called hACE-2, if the cell possesses them, allowing the virus to gain entry to the cell and begin replicating.

In some important ways, SARS-CoV-2 behaves very differently from other coronaviruses, including its close relative SARS-CoV, which was responsible for approximately 8000 infections and 775 deaths. While both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 replicate in the lungs, SARS-CoV-2 also efficiently infects the throat and the nose. However, because levels of hACE-2 are thought to be lower in the throat and nose, there has been a question about whether SARS-CoV-2 does a better job of clinging onto hACE-2.

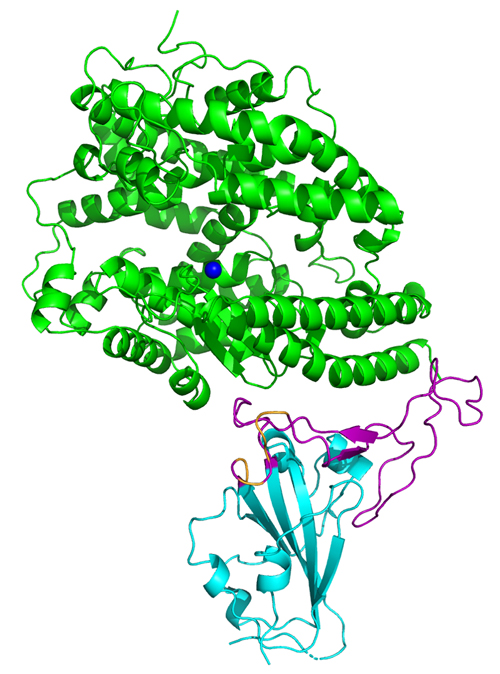

To answer this question, researchers from the University of Minnesota used x-ray crystallography data obtained at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamline 24-ID-E at the APS to create the first atomic-scale three-dimensional (3-D) map of the receptor binding domain (RBD) on the spike protein of a SARS-CoV-2 in complex with hACE-2 [1]. To facilitate crystallization, the researchers designed a chimeric RBD that uses the core from the SARS-CoV RBD as the crystallization scaffold and the RBM from SARS-CoV-2 as the functionally relevant unit. They then compared the crystal structure with those of other coronaviruses, primarily SARS-CoV. (No live viruses are studied at the APS, which is an Office of Science user facility at Argonne.)

The 3-D structure of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 1) shows that the club-like spike proteins it uses to establish infections are more compact and have the potential to latch onto the hACE-2 receptor about four times more strongly than the spike proteins on SARS-CoV. In addition, several residue changes in the SARS-CoV-2 RBD stabilize two virus-binding hotspots at the RBD–hACE-2 interface. This results in the SARS-CoV-2 RBD having a tighter and more stable binding affinity for the human cells.

In theory, this finding would suggest that SARS-CoV-2 should infect humans more easily than SARS-CoV, which it does. Yet, a more recent publication from the researchers used a biochemical technique called a protein pull-down assay to show that although SARS-CoV-2 RBD has a higher hACE2-binding affinity than SARS-CoV RBD, the hACE2 binding affinity of the entire SARS-CoV-2 spike is comparable to or lower than that of SARS-CoV spike. The researchers hypothesize that the reason for this is likely due to the SARS-CoV-2 RBD being less accessible than that of SARS-CoV.

Binding affinity, however, is not the sole determinant of infectivity success. The researchers’ new paper also demonstrates that SARS-CoV-2 does a better job of evading the human immune system. It’s likely this aspect of the virus that ultimately determines its ability to infect more humans than SARS-CoV.

The researchers went on to compare the structure of SARS-CoV-2 with related strains found in bats and pangolins. They found that both animal strains could bind to the same hACE-2 receptor. This evidence supports previous work suggesting the human coronavirus came from bats either directly, or via pangolins acting as an intermediate host. To infect humans, however, the bat or pangolin coronavirus would have needed to undergo mutations to better attach to the human receptor.

The knowledge gained through the biochemical assays and the creation of 3-D crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 not only provides a better understanding of the mechanisms involved in the infectivity of the virus, but also sheds light on its animal origin and offers guidance on vaccine and antiviral drug designs.

― Chris Palmer

See:

[1] Jian Shang, Gang Ye, Ke Shi, Yushun Wan, Chuming Luo, Hideki Aihara, Qibin Geng, Ashley Auerbach, and Fang Li, “Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2,” Nature 581, 221 (14 May 2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y

Author affiliation: University of Minnesota

Correspondence: * lifang@umn.edu

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01AI089728 and R01AI110700 (to F.L.) and R35GM118047 (to H.A.). We thank staff at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team for assistance in data collection. The Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines are funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences from the National Institutes of Health (P30 GM124165). The Eiger 16M detector on the 24-ID-E beamline is funded by a NIH-ORIP HEI grant (S10OD021527). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

[2] Jian Shang, Yushun Wan, Chuming Luo, Gang Ye, Qibin Geng, Ashley Auerbach, and Fang Li*, “Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117(21), 11727 (May 26, 2020). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2003138117

Author affiliation: University of Minnesota

Correspondence: * lifang@umn.edu

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01AI089728 and R01AI110700 (to F.L.).

See also: “Researchers Find Key—and Vulnerable—Features of Novel Coronavirus,” University of Minnesota press release and APS/User News.

This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Laboratory is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.