The original Arizona State University news release by Karin Valentine can be read here.

Astrophysical observations have shown that Neptune-like water-rich exoplanets (planets that orbit a star outside the solar system) are common in our galaxy. These “water worlds” are believed to be covered with a thick layer of water, hundreds to thousands of miles deep, above a rocky mantle. While water-rich exoplanets are common, their composition is very different from Earth, so there are many unknowns in terms of these planets’ structure, composition and geochemical cycles. In seeking to learn more about these planets, a multi-institution team of researchers, led by Arizona State University (ASU) in carrying out experiments at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), has provided one of the first mineralogy lab studies for water-rich exoplanets. The results of their study were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

“Studying the chemical reactions and processes is an essential step toward developing an understanding of these common planet types,” said study co-author Dan Shim, of ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration.

The general scientific conjecture is that water and rock form separate layers in the interiors of water worlds. Because water is lighter, underneath the water layer in water-rich planets, there should be a rocky layer. However, the extreme pressure and temperature at the boundary between water and rocky layers could fundamentally change the behaviors of these materials.

To simulate this high pressure and temperature in the lab, lead author and ASU research scientist Carole Nisr conducted experiments at Shim’s Lab for Earth and Planetary Materials at ASU using high-pressure diamond-anvil cells.

For their experiment, the team immersed silica in water, compressed the sample between diamonds to a very high pressure, then heated the sample with laser beams to over a few thousand degrees Fahrenheit.

The team also conducted laser heating at the APS at Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois. To monitor the reaction between silica and water, x-ray diffraction data were collected at the APS while the laser heated the sample at high pressures applied by a diamond anvil cell. These experiments were carried out at the GeoSoilEnviroCARS 13-ID-D x-ray beamline, and the High Pressure CAT x-ray beamline 16-ID-B.

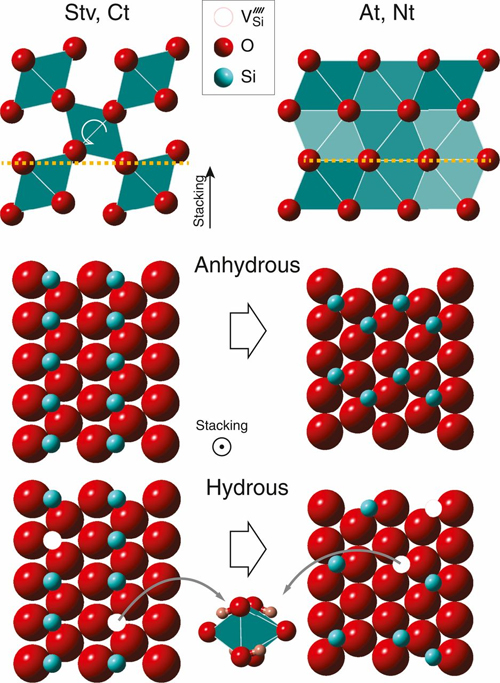

What they found was an unexpected new solid phase with silicon, hydrogen, and oxygen all together.

“Originally, it was thought that water and rock layers in water-rich planets were well-separated,” Nisr said. “But we discovered through our experiments a previously unknown reaction between water and silica and stability of a solid phase roughly in an intermediate composition. The distinction between water and rock appeared to be surprisingly 'fuzzy' at high pressure and high temperature.”

The researchers hope that these findings will advance our knowledge on the structure and composition of water-rich planets and their geochemical cycles.

“Our study has important implications and raises new questions for the chemical composition and structure of the interiors of water-rich exoplanets,” Nisr said. “The geochemical cycle for water-rich planets could be very different from that of the rocky planets, such as Earth.”

See: Carole Nisr1, Huawei Chen1, Kurt Leinenweber1 , Andrew Chizmeshya1, Vitali B. Prakapenka2, Clemens Prescher2, Sergey N. Tkachev2, Yue Meng3, Zhenxian Liu4, and Sang-Heon Shim1, “Large H2O solubility in dense silica and its implications for the interiors of water-rich planets,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, first published April 20, 2020. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1917448117

Author affiliations: 1Arizona State University, 2The University of Chicago, 3Argonne National Laboratory, 4University of Illinois at Chicago

Correspondence: * SHDShim@asu.edu

The work has been supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) Grant EAR1338810 and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Grant 80NSSC18K0353. C.N., H.C., and S.-H.S. were supported partially by the Keck Foundation (PI: P. Buseck). GeoSoilEnvitoCARS is supported by NSF Earth Science Grant EAR-1128799 and U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) GeoScience Grant DE-FG02-94ER14466. High Pressure CAT is supported by DOE-National Nuclear Security Administration Grant DE-NA0001974 and DOE-Basic Energy Sciences Grant DE-FG02-99ER45775. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The APS is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. Each year, the APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of more than 5,000 researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. Researchers using the APS produce over 2,000 publications each year detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility. APS x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.