The original University of Oxford press release can be read here.

Atoms in most metals and alloys are arranged in a regular pattern. Imperfections in this crystal structure have a dramatic effect on the properties of the material. New research at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) allows the nano-scale examination of these defects and the distortions they cause in the surrounding material. The study, published in Physical Review Materials, promises new insights for the optimization of high-performance materials for aerospace applications and power generation.

Felix Hofmann Associate Professor at the Department of Engineering Science, University of Oxford, and lead author on the study, said, “Detailed knowledge of the structure of crystal defects is essential for optimizing materials performance. Normally you think of defects as being bad; however, there is a fantastic opportunity here to enhance material properties by defect engineering.

“The key element is being able to probe the distortions defects’ cause in the surrounding material, because it is through their distortions that defects communicate and interact.”

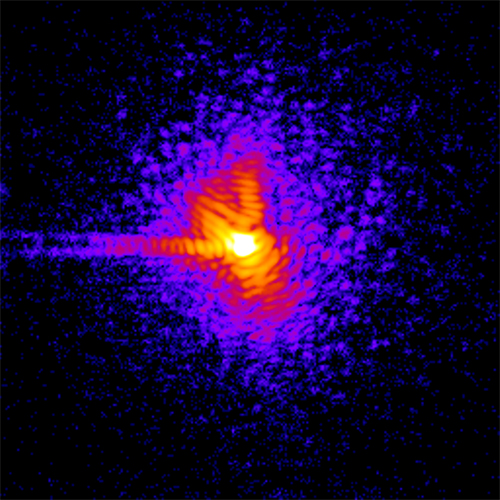

The new research, carried out by researchers from the University of Oxford (UK) in collaboration with colleagues at the APS (an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory) used the X-ray Science Division (XSD) 34-ID-E x-ray beamline at the APS for Laue diffraction studies, and the XSD 34-ID-C beamline at the APS for application of the Bragg coherent diffraction imaging (BCDI) technique. Like a medical x-ray, BCDI allows the three-dimensional imaging of defects, but with more than 10,000 times higher spatial resolution. However, BCDI doesn’t just “see” the defects; it can measure the distortions they cause in the surrounding material. Nick Phillips, second author on the study and a postdoctoral research associate at Oxford’s Engineering Science Department, said, “Our new analysis approach allows us to completely characterize the lattice distortions defects cause. Importantly our method is completely general, so we can be sure it will work no matter what defects our samples contain. This is a real breakthrough in the field.”

To work, BCDI requires very small samples―less than a micron in diameter. In the past, this has meant that it could only be used to investigate materials that naturally form suitably small particles. Unfortunately, almost none of the most important engineering materials fall into this category. Another problem is that until researchers examine their nano-sized samples they cannot know whether the samples in fact contain the defect they’re trying to study.

Hofmann’s team developed a new approach that overcomes these hurdles. This method makes it possible to first identify specific defects of interest in a bulk specimen, and to then create a micron-sized BCDI sample containing these defects. This is done using an approach called “focused ion beam machining” (FIB) that uses a beam of focused ions to cut and shape materials with nano-scale precision. However, FIB has its drawbacks. “BCDI has excellent sensitivity to lattice strain,” Phillips explains, “and the presence of FIB damage can cause severe complications. Even a single FIB imaging scan can leave behind large strain fields that complicate BCDI reconstructions and can obscure more subtle strain fields of interest. The key aspect of our new FIB preparation method for BCDI samples is that it provides a reliable approach for minimizing FIB damage and associated spurious lattice strain fields.”

“Together, these new capabilities open the door to BCDI as a microscopy tool for studying complex, real-world materials.”

In the journal article, the team demonstrates the effectiveness of their new technique on tungsten, the most promising material for armor components in future nuclear fusion rectors. In service, tungsten armor is exposed to intense heat and radiation levels for tens of years. This extreme environment causes defects within the metal, so it is vital for engineers to understand how those defects might impact the material’s strength―particularly in the event of an accident.

“We’re very excited to publish this ground-breaking research,” said Hofmann. “It’s the culmination of a 9-year ambition, and a lot of work has gone into it. This technique has the potential to change our understanding of the advanced alloys used in industries such as aerospace and nuclear power. We really want to get it out there as an enabling tool for the research community.”

See: Felix Hofmann1*, Nicholas W. Phillips1, Suchandrima Das1, Phani Karamched1, Gareth M. Hughes1, James O. Douglas1, Wonsuk Cha2, and Wenjun Liu2, “Nanoscale imaging of the full strain tensor of specific dislocations extracted from a bulk sample,” Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 013801 (2020). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.4.013801

Author affiliations: 1University of Oxford, 2Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: *felix.hofmann@eng.ox.ac.uk

F.H. and N.W.P. acknowledge funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 714697). S.D. acknowledges support from The Leverhulme Trust under Grant No. RPG-2016-190. J.O.D. was supported by EPSRC Grant No. EP/P005101/1.

This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The APS is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. The APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. These x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being. Each year, more than 5,000 researchers use the APS to produce over 2,000 publications detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.