The original Virginia Tech press release by Laura Weatherford can be read here.

The original Arizona State University press release by Melinda Weaver can be read here.

Imagine you are flipped upside down and standing on your head. After a few seconds, you would feel pressure in your head due to an increased blood flow. Humans and other vertebrates are known to have physiological reactions to gravity with reactions increasing with body size. A new study by researchers using high-brightness x-rays from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) shows that insects also experience effects of gravity on their cardiovascular systems and that they exhibit active responses to combat these. Their results were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

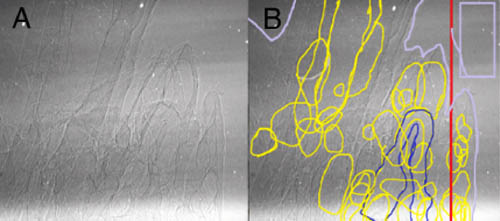

To determine the effect of gravity on Schistocerca americana, commonly known as the American grasshopper, the team of researchers from Arizona State University and Virginia Tech, along with colleagues from the Imaging Group in the APS X-ray Science Division (XSD), collected x-ray images of the grasshoppers using the XSD 32-ID-B,C x-ray beamline at the APS, an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory. They then analyzed the images to observe the insects’ internal systems. In some images, the grasshoppers were head-up, and in others, the grasshoppers’ heads faced the ground.

When analyzing the x-ray images of grasshoppers, the researchers discovered that air sacs located in the head had greatly expanded when the insect was head-up (upright) while air sacs in the abdomen were smaller. When the animal was head-down, the opposite was true: the air sacs in the head were decreased in size while the air sacs in the abdomen were greatly expanded.

“No one expected that a small insect would have any type of response due to their gravitational orientation,” article co-author Jake Socha said, who is also the director of Virginia Tech’s BIOTRANS, an interdisciplinary graduate team of biologists and engineers who work together to study transport in environmental and physiological systems. “This project started by seeing some weird things in x-ray images and asking questions.”

The study demonstrates how insects adjust their cardiovascular and respiratory activity in response to gravity. “Interestingly, this has never been looked at in invertebrates,” said co-author Jon Harrison of Arizona State University. “It’s something I’ve always been interested in because the blood is not in vessels. It’s an open circulatory system so the typical biologist would probably say, well the blood must just be sloshing around in there, but we actually don’t know much about what’s going on with blood circulation in insects.”

Their discoveries indicate that fluid pressure due to gravity may affect the insect's body and its bodily systems, just as in humans. This is counterintuitive to prior scientific thought and could have larger implications in future research.

Socha compared this effect to diving into a deep swimming pool. As a person dives lower down into the water, there is more pressure. This same concept applies to the grasshopper’s body. The part of the body that is lower, or beneath the rest of the body, has higher blood pressure and thus, the air sacs are compressed.

However, when the insect is awake, the response is different. The air sacs change less in response to orientation. To further analyze this active response, called functional valving or compartmentalization, the researchers further examined the grasshopper.

To test whether grasshoppers have active responses to gravitational effects on fluid flow, the researchers compared the effects of body orientation on air sac size in awake vs. anesthetized animals. Awake insects exhibited much less of an effect of gravity on air sac size, suggesting active compensation, just as occurs in humans.

Grasshoppers and other insects have open circulatory systems, which means that their blood is not contained in closed arteries or veins. Classic understanding of open circulatory systems is that blood flows freely within the body, like liquid in a bottle, and that pressures inside the body would all be similar. The research team discovered that these insects, in fact, could separate, or alter, internal body pressures with a flexible valving system.

“This was remarkable,” Socha said. “Earlier this year, we published a paper with a similar finding. We analyzed beetles and found they had active body responses to compensate for forces on their bodies. So, we were interested in the other physiological responses of other animals.”

The researchers also found that grasshoppers’ heart rates change with orientation just as observed in humans. Humans sometimes feel dizzy when standing up too quickly because gravity impedes blood flow to the brain; fast-acting reflexes cause the heart to pump harder to overcome this gravity effect.

Even though insects do not have a closed circulatory system with veins and arteries, most insects typically have a tube-like heart. These researchers found that the grasshopper’s heart rate would slow when head-down and beat faster when head-up, thus providing more evidence to point to insects’ systems not only being affected by gravity but having active, physiological responses to compensate for gravity’s effects, contrary to scientific prediction.

“If you watch grasshoppers, they’re all over the place,” said Harrison. “They’re head up, head down, sideways. “They’re very flexible in their body orientation, as are most insects. And now we know that when they change their orientation they have to respond to gravity just like humans, and they even show many of the same physiological responses. This is a dramatic example showing how similar animals are physiologically, despite how different they may appear.”

“We have multiple indicators pointing to the grasshoppers responding to its body orientation,” Socha said. “They respond physiologically to its orientation relative to gravity and have mechanisms inside its body to be able to deal with it. Grasshoppers are able to change their heart rate, respiratory rate, and functionally compartmentalize their bodies to control pressure.”

See: Jon F. Harrison1, Khaled Adjerid2, Anelia Kassi1, C. Jaco Klok1, John M. VandenBrooks1, Meghan E. Duell1, Jacob B. Campbell1, Stav Talal1, Christopher D. Abdo1, Kamel Fezzaa3, Hodjat Pendar2, and John J. Socha2, “Physiological responses to gravity in an insect,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., first published January 13, 2020 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1915424117

Author affiliations: 1Arizona State University, 2Virginia Tech, 3Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: * j.harrison@asu.edu

Home page photo: https://torange.biz/grasshopper-white-background-34027

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Integrative Organismal Systems (IOS) 1558052 and NSF Emerging Frontiers in Research and Innovation (EFRI) 0938047. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

This research was featured in the January 13, 2020, issue of The New York Times.

The APS is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities. The APS provides high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. These x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being. Each year, more than 5,000 researchers use the APS to produce over 2,000 publications detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.