The original Carnegie Institution for Science press release can be read here.

The original Carnegie Institution for Science press release can be read here.

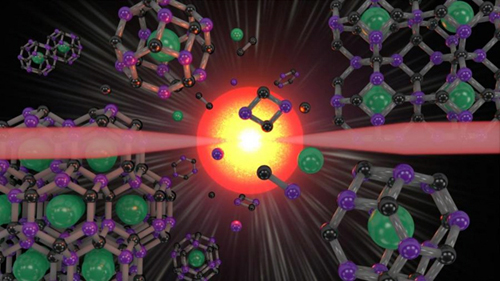

A long-sought-after class of "superdiamond" carbon-based materials with tunable mechanical and electronic properties was predicted and synthesized by a research team from the Carnegie Institution for Science. Their novel synthesis and characterization was carried out at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) and the results were published in the journal Science Advances.

Carbon is the fourth-most-abundant element in the universe and is fundamental to life as we know it. It is unrivaled in its ability to form stable structures, both by itself and with other elements.

A material's properties are determined by how its atoms are bonded and the structural arrangements that these bonds create. For carbon-based materials, the type of bonding makes the difference between the hardness of diamond, which has three-dimensional “sp3” bonds, and the softness of graphite, which has two-dimensional “sp2” bonds, for example.

Despite the enormous diversity of carbon compounds, only a handful of three-dimensionally, sp3-bonded carbon-based materials are known, including diamond. The three-dimensional bonding structure makes these materials very attractive for many practical applications due to a range of properties including strength, hardness, and thermal conductivity.

“Aside from diamond and some of its analogs that incorporate additional elements, almost no other extended sp3 carbon materials have been created, despite numerous predictions of potentially synthesizable structures with this kind of bonding,” said Carnegie researcher and article co-author Timothy Strobel. “Following a chemical principle that indicates adding boron into the structure will enhance its stability, we examined another three-dimensionally-bonded class of carbon materials called ‘clathrates,’ which have a lattice structure of cages that trap other types of atoms or molecules.”

Clathrates comprised of other elements and molecules are common and have been synthesized or found in nature. However, carbon-based clathrates have not been synthesized until now, despite long-standing predictions of their existence. Researchers have attempted to create them for more than 50 years.

Strobel, first author Li Zhu (also from Carnegie), and their team from the Warsaw University of Technology (Poland), The University of Chicago, the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, the Ludwig Maximilians Universität (Germany), and University College London (UK) approached the problem through a combined computational and experimental approach.

“We used advanced structure searching tools to predict the first thermodynamically stable carbon-based clathrate and then synthesized the clathrate structure, which is comprised of carbon-boron cages that trap strontium atoms, under high-pressure and high-temperature conditions,” Zhu said. The clathrate was loaded into diamond anvil cells and compressed to the target pressure between 50 and 150 GPa. The samples were then laser heated in situ at high pressures at the GeoSoilEnviro Center for Advanced Radiation Sources (GSECARS) and High Pressure CAT (HPCAT-XSD) sectors at the APS. Temperatures near 3000 K were needed to produce crystalline grains with size comparable to the APS x-ray beam. The team then collected in situ powder x-ray diffraction patterns at the HPCAT-XSD 16-ID x-ray beamline and at the GeoSoilEnviroCARS 13-ID beamline. (The APS is an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory.)

The result is a three-dimensional, carbon-based framework with diamond-like bonding that is recoverable to ambient conditions. But unlike diamond, the strontium atoms trapped in the cages make the material metallic―meaning it conducts electricity―with potential for superconductivity at notably high temperature.

What's more, the properties of the clathrate can change depending on the types of guest atoms within the cages.

“The trapped guest atoms interact strongly with the host cages,” Strobel said. “Depending on the specific guest atoms present, the clathrate can be tuned from a semiconductor to a superconductor, all while maintaining robust, diamond-like bonds. Given the large number of possible substitutions, we envision an entirely new class of carbon-based materials with highly tunable properties.”

“For anyone who is into―or whose kids are into―Pokémon, this carbon-based clathrate structure is like the Eevee of materials,” joked Zhu. “Depending which element it captures, it has different abilities.”

See: Li Zhu1, Gustav M. Borstad1‡, Hanyu Liu1‡‡, Piotr A. Guńka1,2, Michael Guerette1, Juli-Anna Dolyniuk1, Yue Meng1‡‡‡, Eran Greenberg3, Vitali B. Prakapenka3, Brian L. Chaloux4, Albert Epshteyn4, Ronald E. Cohen1,5,6, Timothy A. Strobel1*, “Carbon-boron clathrates as a new class of sp3-bonded framework materials,” Sci. Adv. 6,: eaay8361 (10 January 2020). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aay8361

Author affiliations: 1Carnegie Institution for Science, 2Warsaw University of Technology, 3The University of Chicago, 4U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, 5Ludwig Maximilians Universität, 6University College London Present addresses: ‡University of Memphis, ‡‡Jilin University, ‡‡‡Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: * tstrobel@carnegiescience.edu

This work was supported by DARPA under grant no. W31P4Q1310005. Additional support was provided by the Energy Frontier Research in Extreme Environments (EFree) Center, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science under award no. DE-SC0001057. P.A.G. thanks the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange and Warsaw University of Technology for financial support. R.E.C. was also supported by the European Research Council Advanced Grant ToMCaT. HPCAT-XSD operations are supported by the DOE-National Nuclear Security Administration Office of Experimental Sciences. GeoSoilEnviroCARS is supported by the National Science Foundation-Earth Sciences (EAR-1634415) and DOE-GeoSciences (DE-FG02-94ER14466). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

The APS is one of the world’s most productive x-ray light source facilities, providing high-brightness x-ray beams to a diverse community of researchers in materials science, chemistry, condensed matter physics, the life and environmental sciences, and applied research. These x-rays are ideally suited for explorations of materials and biological structures; elemental distribution; chemical, magnetic, electronic states; and a wide range of technologically important engineering systems from batteries to fuel injector sprays, all of which are the foundations of our nation’s economic, technological, and physical well-being. Each year, more than 5,000 researchers use the APS to produce over 2,000 publications detailing impactful discoveries, and solve more vital biological protein structures than users of any other x-ray light source research facility.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.