Cancer is caused by uncontrolled cellular replication. Of course, there can be no cellular replication without DNA replication. Doctors have been using DNA-damaging drugs to kill cancer for decades, but often malignant cells overcome the DNA damage and continue to replicate, leading to poor health outcomes. A key to the cancer cells’ resilience is a special class of polymerases—enzymes that catalyze DNA replication—that can essentially ignore DNA damage and copy the DNA, whatever shape it’s in, even if it means creating new malignant cells with faulty DNA. Depending on the nature of the DNA damage, sometimes this process can trigger secondary malignancies. Recently, researchers discovered JH-RE-06, a small-molecule inhibitor of one of these special polymerases. To understand how the inhibitor works, a multi-institution team of researchers collected x-ray diffraction data at the APS, in the process uncovering an unusual inhibition mechanism. Combining JH-RE-06 with existing chemotherapies may offer doctors a new tool to kill even the most obstinate cancers.

Cancer is caused by uncontrolled cellular replication. Of course, there can be no cellular replication without DNA replication. Doctors have been using DNA-damaging drugs to kill cancer for decades, but often malignant cells overcome the DNA damage and continue to replicate, leading to poor health outcomes. A key to the cancer cells’ resilience is a special class of polymerases—enzymes that catalyze DNA replication—that can essentially ignore DNA damage and copy the DNA, whatever shape it’s in, even if it means creating new malignant cells with faulty DNA. Depending on the nature of the DNA damage, sometimes this process can trigger secondary malignancies. Recently, researchers discovered JH-RE-06, a small-molecule inhibitor of one of these special polymerases. To understand how the inhibitor works, a multi-institution team of researchers collected x-ray diffraction data at the APS, in the process uncovering an unusual inhibition mechanism. Combining JH-RE-06 with existing chemotherapies may offer doctors a new tool to kill even the most obstinate cancers.

DNA replication is the very essence of life, allowing hereditary information to be transferred from cell to cell and from generation to generation. The cell has an entire machinery dedicated to the preservation and maintenance of DNA, yet sometimes, to save a life, the cell must replicate its DNA in spite of damage. In these cases, the cell engages a process known as “translesion synthesis” (TLS), which deploys TLS DNA polymerases to replicate DNA in spite of mutations. Cancer cells that exploit TLS to overcome mutations caused by DNA-damaging medications are said to have chemotherapeutic resistance.

TLS is a two-step process involving an initiation TLS polymerase and an elongation TLS polymerase. Scientists looking for inhibitors of TLS polymerases have been hampered due to similarities between these enzymes and the polymerases that replicate normal DNA. An inhibitor that blocked both TLS polymerases and normal polymerases would not be a good drug, as it would lead to the death of normal healthy cells. Zhou’s team found a way around this by targeting a specific protein-protein interaction between an insertion TLS polymerase and an elongation TLS polymerase that doesn’t exist in the standard polymerases. The researchers performed an ELISA assay screen of around 10,000 structurally diverse compounds in search of inhibitors of this interaction, and were rewarded with a hit: JH-RE-06.

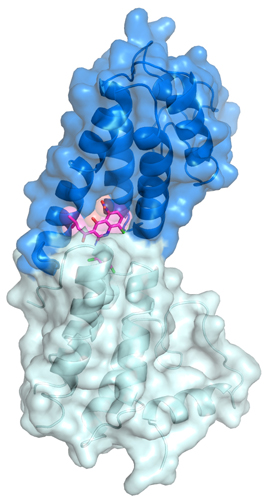

As a next step, Zhou’s the team probed the atomic details of inhibition by crystallizing a fragment of the polymerase along with JH-RE-06. Using data from studies at the SER-CAT beamline 22-ID-D the APS, the researchers solved a 1.50-Å-resolution crystal structure of the inhibitor-polymerase complex. That’s when they got a surprise. The inhibitor bound on a relatively featureless side of the polymerase, inducing dimerization that prevented the interaction of the insertion polymerase with the elongation polymerase.

The big test was whether JH-RE-06 had an impact on living cells. Cisplatin is a chemotherapy that works by damaging DNA, and cisplatin resistance is not uncommon. To test JH-RE-06, the researchers performed experiments on the effects of cisplatin with and without the inhibitor in a series of human cancer cell lines, including fibrosarcoma, melanoma, and prostate adenocarcinoma, as well as mouse lung adenocarcinoma cells. The researchers also tested the combination in non-cancer human and mouse cells. The researchers found that JH-RE-06 enhanced the cytotoxicity of cisplatin in cancer cell lines, but not in normal cell lines, as they hoped. The researchers also combined JH-RE-06 with other agents that damage DNA beyond cisplatin and found similar results. The most encouraging results came from a xenograft mouse model of human melanoma; those mice treated with a combination of JH-RE-06 and cisplatin survived longer than those treated with saline or either agent alone.

By improving chemotherapy, JH-RE-06 represents a novel class of adjuvants and may perhaps someday become a standard strategy for fighting cancer. — Erika Gebel Berg

See: Jessica L. Wojtaszek1‡, Nimrat Chatterjee2, Javaria Najeeb1, Azucena Ramos2, Minhee Lee3, Ke Bian4, Jenny Y. Xue3‡‡, Benjamin A. Fenton1, Hyeri Park3, Deyu Li5, Michael T. Hemann2*, Jiyong Hong1,3**, Graham C. Walker2***, and Pei Zhou1*, “A Small Molecule Targeting Mutagenic Translesion Synthesis Improves Chemotherapy,” Cell 178, 152 (June 27, 2019).

DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.028

Author affiliations: 1Duke University Medical Center, 2Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 3Duke University, 4University of Rhode Island Present address: ‡National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, ‡‡Weill Cornell/Rockefeller/Sloan Kettering Tri-Institutional M.D.-Ph.D. Program

Correspondence: * hemann@mit.edu,

** jiyong.hong@duke.edu,

*** gwalker@mit.edu,

**** peizhou@biochem.duke.edu

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA191448 to P.Z. and J.H.; CA213042 to D.L.), the Alexander and Margaret Stewart Trust (to P.Z.), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (ES028303 to G.C.W.; ES028865 to D.L.), Duke University (to J.H.), and the Center for Precision Cancer Medicine at MIT (to M.T.H.). G.C.W. is an American Cancer Society Professor. SER-CAT is supported by its member institutions and equipment grants (S10_RR25528 and S10_RR028976) from the National Institutes of Health. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.