The regulation of many cellular processes relies on interactions between sphingomyelin and cholesterol, two essential lipids in the cell’s plasma membrane. Collecting diffraction data at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), researchers examined the three-dimensional molecular interaction between the lipid-binding protein Ostreolysin A and sphingomyelin/cholesterol complexes. The results of this study improved current understanding of how these lipids interact to carry out their regulatory functions and will instruct further research in this area.

The regulation of many cellular processes relies on interactions between sphingomyelin and cholesterol, two essential lipids in the cell’s plasma membrane. Collecting diffraction data at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), researchers examined the three-dimensional molecular interaction between the lipid-binding protein Ostreolysin A and sphingomyelin/cholesterol complexes. The results of this study improved current understanding of how these lipids interact to carry out their regulatory functions and will instruct further research in this area.

Cholesterol and sphingomyelin are present at high concentrations in the plasma membranes of animal cells. The interaction between these two lipids at this location is vital for controlling many signaling processes within the cell. One of these key processes is regulation of the synthesis and uptake of cholesterol to control its levels in cells. This is important because the stability and integrity of the plasma membrane depends on proper levels of cholesterol. However, the exact mechanism by which these two essential lipids interact at the structural level remains poorly understood.

This lack of understanding relates, at least in part, to the fact that the plasma membrane’s lipid bilayer region is a liquid and liquids do not have defined structures, which makes the interaction between lipids difficult to study. Therefore, scientists investigating this interaction need to find some way to trap lipids in states in which they may be bound to each other—for example in a sphingomyelin/cholesterol complex.

With this in mind, researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center performed a study, hoping to gain further insight into this interaction. First, they aimed to find a protein that would specifically bind to sphingomyelin/cholesterol complexes. They screened many candidate proteins and found one called Ostreolysin A that binds to sphingomyelin when sphingomyelin is bound to cholesterol, but not when it is free from cholesterol.

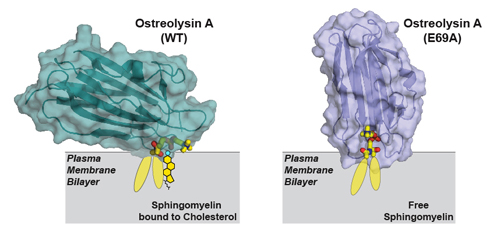

Next, the researchers used diffraction data collected at the Structural Biology Center (SBC-XSD) beamline 19-ID-D at the APS (an Office of Science user facility at Argonne) to solve the structure of Ostreolysin A when it was bound to the lipids (Fig. 1). Their analyses demonstrated how the protein’s binding surface recognizes sphingomyelin when sphingomyelin is bound to cholesterol, but not when it is free of cholesterol.

This new information about the structure of the Ostreolysin A binding surface allowed the researchers to then model how the lipids must be arranged in the membrane. In this way, they were able to develop more understanding of the liquid membrane. They also showed that the conformation of sphingomyelin in the plasma membrane changes between two forms (Fig. 1), depending on whether it is bound to cholesterol or free of it.

Indeed, a critical point in their study was discovering a mutation in Ostreolysin A that eliminated its ability to discriminate between the two forms of sphingomyelin. The researchers solved the structure of this mutant and were able to determine how the binding surface on Ostreolysin A changed, which therefore informed them about how sphingomyelin adopted its two different conformations.

One interesting implication of these findings is that lipids can adopt different conformations in the cell’s plasma membrane. More typically, we think of proteins as having different conformations. But lipids can also exist in different states, and proteins can specifically recognize one lipid state but not another.

Overall, the results of this study will help guide further research into how essential lipids interact to regulate key intracellular signalling processes. — Nicola Parry

See: Shreya Endapally, Donna Frias, Magdalena Grzemska, Austin Gay, Diana R. Tomchick, and Arun Radhakrishnan*, “Molecular Discrimination between Two Conformations of Sphingomyelin in Plasma Membranes,” Cell 176(5), 1040 (February 21, 2019). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.042

Author affiliation: University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Correspondence: *arun.radhakrishnan@utsouthwestern.edu

This work was supported by the Welch Foundation (I-1793), the American Heart Association (12SDG12040267), and the National Institutes of Health (HL20948). SBC-XSD is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)-Biological and Environmental Research under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.