The original University of Michigan press release by Emily Kagey can be read here.

The original University of Michigan press release by Emily Kagey can be read here.

Research at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), and led by the University of Michigan Life Sciences Institute, has solved a nearly 50-year-old mystery of how nature produces a large class of bioactive chemical compounds. Called prenylated indole alkaloids, the compounds were first discovered in fungi in the 1970s. Since then, they have attracted considerable interest for their wide range of potential applications as useful drugs. One compound is already used worldwide as an antiparasitic for livestock.

The findings, which were co-authored by senior authors Prof. David H. Sherman and Prof. Janet L. Smith of Michigan and colleagues Prof. Robert M. Williams and Robert Paton from Colorado State University, and Prof. Ken Houk from the University of California, Los Angeles, were published in the journal Nature Chemistry.

Understanding how the fungi build these chemicals is essential to reproducing them and creating variants in the lab for new applications. The fungi's genes encode enzymes, and these enzymes use very simple building blocks to perform each step to build the complex molecule.

But despite the longstanding knowledge about these compounds, researchers have not been able to tease apart the precise enzymes and reactions that the fungi use to produce them.

"If we can actually isolate the genes involved and make these enzymes, we should be able to recreate the entire bio-assembly line in a test tube," said Qingyun Dan, a researcher in the lab of Janet Smith at the Life Sciences Institute and a lead author on the study. "But, until now, no lab has been able to do so."

Using a collaborative approach over the course of a decade that combined synthetic chemistry, genetics, enzymology, and computational chemistry, as well as structural biology at the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and National Cancer Institute (GM/CA-XSD) x-ray beamlines at the APS (beamline 23-ID-D for obtaining Wild-type MalC data and 23-ID-B for all other diffraction data) the researchers have revealed the process — and uncovered a surprising chemical twist. The final step in the assembly process is a reaction that is nearly unprecedented in nature: the Diels-Alder reaction.

"This reaction is one of the fundamentals of synthetic organic chemistry, going back to the 1920s when it was first discovered," said LSI faculty member David Sherman, one of the senior authors of the study.

"But even within the last few years, there has been major debate in the field about whether this reaction actually exists in nature. It's just the most phenomenal, unexpected path to this fascinating class of indole alkaloids."

The researchers believe that discovering the enzyme that enables the Diels-Alder reaction—and resolving how these compounds are made in nature—now opens two exciting paths forward.

First, the particular enzyme that catalyzes this Diels-Alder reaction could help improve one of the most commonly used chemical reactions. This enzyme performs the reaction with specificity that far outperforms what can commonly be achieved in the lab, meaning it creates only the one desired compound and no unintended byproducts.

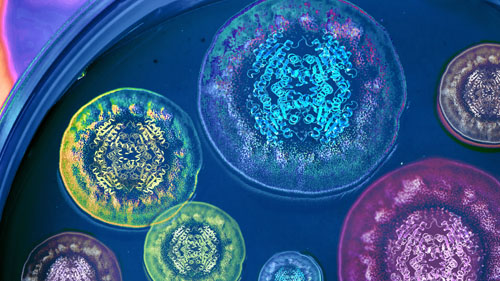

Second, because the researchers were able to obtain a crystal structure of the enzyme performing the Diels-Alder reaction, they now have a clear picture of how the enzyme directs the reaction in nature—and how it might be harnessed to create new compounds in the future.

"This is a very good example of the explanatory power of crystal structures," said Sean Newmister, a researcher in Sherman's lab and a lead author on the study. "We gain mechanistic insight into the activity of the enzyme we're studying, but also insight into how to use this as a tool to synthesize new chemical compounds with biological activities. And that's really exciting."

See: Qingyun Dan1, Sean A. Newmister1, Kimberly R. Klas2, Amy E. Fraley1, Timothy J. McAfoos2, Amber D. Somoza2, James D. Sunderhaus2, Ying Ye1, Vikram V. Shende1, Fengan Yu1, Jacob N. Sander3, W. Clay Brown1, Le Zhao2, Robert S. Paton2, K. N. Houk3, Janet L. Smith1, David H. Sherman1,* and Robert M. Williams2,4**, “Fungal indole alkaloid biogenesis through evolution of a bifunctional reductase/Diels–Alderas,” Nat. Chem., published 23 September 2019. DOI: 10.1038/s41557-019-0326-6

Author affiliations: 1University of Michigan, 2Colorado State University, 3University of California, Los Angeles, 4University of Colorado Cancer Center

Correspondence: *davidhs@umich.edu; **robert.williams@colostate.edu

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 CA070375 to (R.M.W. and D.H.S.), R35 GM118101, and the Hans W. Vahlteich Professorship (to D.H.S.), and R01 DK042303 and the Margaret J. Hunter Professorship (to J.L.S.). J.N.S. and K.N.H. acknowledge support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under awards F32GM122218 (to J.N.S.) and R01GM124480 (to K.N.H.). GM/CA-XSD is supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM-12006) and National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002). The Eiger 16M detector was funded by an NIH–Office of Research Infrastructure Programs, High-End Instrumentation Grant (1S10OD012289-01A1). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.