The original article from Northwestern University’s “Northwestern Now,” by Amanda Morris, can be read here.

The original article from Northwestern University’s “Northwestern Now,” by Amanda Morris, can be read here.

It’s not an electron. But it sure does act like one.

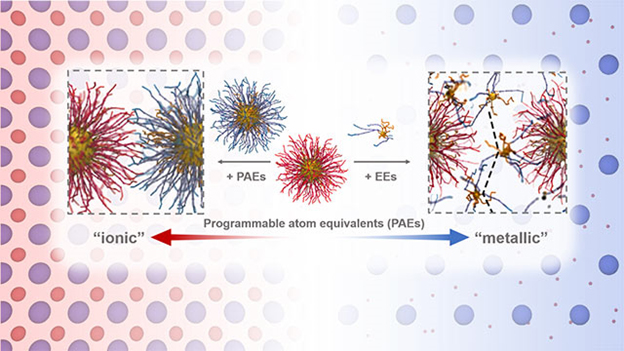

Northwestern University researchers using a number of experimental resources, including the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), have made a strange and startling discovery: Nanoparticles engineered with DNA in colloidal crystals — when extremely small — behave just like electrons. Not only has this finding upended the current, accepted notion of matter, it also opens the door for new possibilities in materials design.

“We have never seen anything like this before,” said Northwestern University’s Monica Olvera de la Cruz, who made the initial observation through computational work. “In our simulations, the particles look just like orbiting electrons.”

With this discovery, the researchers introduced a new term called “metallicity,” which refers to the mobility of electrons in a metal. In colloidal crystals, tiny nanoparticles roam similarly to electrons and act as a glue that holds the material together.

“This is going to get people to think about matter in a new way,” said Northwestern’s Chad Mirkin, who led the experimental work. “It’s going to lead to all sorts of materials that have potentially spectacular properties that have never been observed before. Properties that could lead to a variety of new technologies in the fields of optics, electronics and even catalysis.”

The paper was published in the journal Science.

Olvera de la Cruz is the Lawyer Taylor Professor of Materials Science and Engineering in Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering. Mirkin is the George B. Rathmann Professor of Chemistry in Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences.

Mirkin’s group previously invented the chemistry for engineering colloidal crystals with DNA, which has forged new possibilities for materials design. In these structures, DNA strands act as a sort of smart glue to link together nanoparticles in a lattice pattern.

“Over the past two decades, we have figured out how to make all sorts of crystalline structures where the DNA effectively takes the particles and places them exactly where they are supposed to go in a lattice,” said Mirkin, founding director of the International Institute for Nanotechnology.

In these previous studies, the particles’ diameters are on the tens of nanometers length scale. Particles in these structures are static, fixed in place by DNA. In the current study, however, Mirkin and Olvera de la Cruz shrunk the particles down to 1.4 nanometers in diameter in computational simulations. This is where the magic happened.

“The bigger particles have hundreds of DNA strands linking them together,” said Olvera de la Cruz. “The small ones only have four to eight linkers. When those links break, the particles roll and migrate through the lattice holding together the crystal of bigger particles.”

Mirkin’s team experiments, including small-angle x-ray scattering characterization at the DuPont-Northwestern-Dow Collaborative Access Team x-ray beamline 5-ID at the APS, agree with Olvera de la Cruz’s team’s computational observations. Because this behavior is reminiscent to how electrons behave in metals, the researchers call it “metallicity.” (The APS is an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory.)

“A sea of electrons migrates throughout metals, acting as a glue, holding everything together,” Mirkin explained. “That’s what these nanoparticles become. The tiny particles become the mobile glue that holds everything together.”

Olvera de la Cruz and Mirkin next plan to explore how to exploit these electron-like particles in order to design new materials with useful properties. Although their research used gold nanoparticles, Olvera de la Cruz said “metallicity” applies to other classes of particles in colloidal crystals.

“In science, it’s really rare to discover a new property, but that’s what happened here,” Mirkin said. “It challenges the whole way we think about building matter. It’s a foundational piece of work that will have a lasting impact.”

See: Martin Girard1, Shunzhi Wang1, Jingshan S. Du1, Anindita Das1, Ziyin Huang1, Vinayak P. Dravid1, Byeongdu Lee2, Chad A. Mirkin1**, Monica Olvera de la Cruz1*, “Particle analogs of electrons in colloidal crystals,” Science 364, 1174 (21 June 2019). DOI: 10.1126/science.aaw8237

Author affiliations: 1Northwestern University, 2Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: *m-olvera@northwestern.edu, **chadnano@northwestern.edu

This material is based on work supported by the Center for Bio-Inspired Energy Science (CBES), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences (DE-SC0000989, for computational studies), the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-17-1-0348, for synthesis, spectroscopy, and electron microscopy), the Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship program sponsored by the Basic Research Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering and funded by the Office of Naval Research (N00014-15-1-0043), the Sherman Fairchild Foundation (for electron microscopy and computational support), and the Biotechnology Training Program of Northwestern University (NU, for cryo-TEM). This work made use of facilities at the NUANCE Center at NU (National Science Foundation [NSF] ECCS-1542205 and NSF DMR-1720139), the Structural Biology Facility at NU (NCI CCSG P30 CA060553), and the DuPont-Northwestern-Dow Collaborative Access Team facility, which is supported by Northwestern University, E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., and The Dow Chemical Company. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.