Adapted from an article published online by eLife

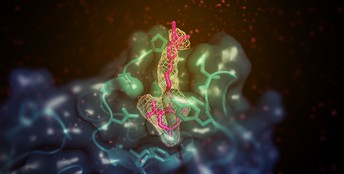

Scientists have determined the structure of the activated form of an enzyme that helps to return excess cholesterol to the liver, a study in the journal eLife reports. The research by a team from the University of Michigan, the National Institutes of Health, and Purdue University reveals how a drug-like chemical stimulates the action of the lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) enzyme. The research, aided by studies at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), also suggests that future drugs using the same mechanism could be used to restore LCAT function in people with familial LCAT deficiency (FLD), a rare inherited disease that puts them at risk of eye problems, anemia, and kidney failure.

LCAT helps high-density lipoprotein (HDL) – known as the ‘good’ cholesterol – to remove cholesterol from the blood by converting the lipid into a form that is easier to package and transport. There are more than 90 known mutations in LCAT, which can cause either a partial loss of activity (known as ‘fish-eye disease’) or full loss (FLD). Boosting LCAT activity could therefore be beneficial in treating people with coronary heart disease and LCAT deficiencies, but the mechanisms by which it can be activated are poorly understood.

“In this study, we used structural biology to understand how a patented LCAT activator binds to LCAT and how it promotes cholesterol transport,” said lead author Kelly Manthei, a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Michigan Life Sciences Institute. “We also asked if the compound could help recover activity of LCAT enzymes that have commonly observed mutations seen in FLD.”

The team used x-ray crystallography at the Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team 21-ID-G x-ray beamline at the APS to look at the LCAT enzyme stabilized in its active state with two different chemicals – the activator molecule, and a second compound that mimics a substrate bound to the enzyme. The two chemicals had more of an effect on the protein when presented together than when presented separately, which suggested that they bind to the enzyme in different places. (The APS is an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory.)

Further analysis found that the activator molecule, unlike other known LCAT activators, binds to a region close to where HDL attaches. However, the activator did not help LCAT bind to the HDL more effectively, which led the team to speculate that it instead helps to transfer cholesterol and lipids into the catalytic center of the enzyme, so that it can convert it into cargo for transport in HDL.

Having established this mode of action, the researchers tested whether this molecule could help recover the cholesterol-transport function of a mutant LCAT enzyme. They made a version of the enzyme with a mutation commonly seen in FLD patients, and then tested its ability to bind to HDL and convert cholesterol in the presence or absence of the activator molecule. They were excited to find that the activator could partly reverse the loss of activity in the mutant enzymes, resulting in comparable cholesterol conversion to the normal enzyme.

“Our results will help scientists design compounds that can better target LCAT so they might be of therapeutic benefit for heart disease and FLD patients,” said senior author John Tesmer, Walther Professor in Cancer Structural Biology at Purdue University. “Future efforts will be to examine whether patients with other LCAT genetic mutations could benefit from the compounds used in this study, and to design molecules with improved pharmacological properties for further development.”

See: Kelly A. Manthei1, Shyh-Ming Yang2, Bolormaa Baljinnyam2, Louise Chang1, Alisa Glukhova1, Wenmin Yuan1, Lita A. Freeman2, David J. Maloney2, Anna Schwendeman1, Alan T. Remaley2, Ajit Jadhav2, John J.G. Tesmer3*, “Molecular basis for activation of lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase by a compound that increases HDL cholesterol,” eLife 7:e41604 (2018). DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.41604

Author affiliations: 1University of Michigan, 2National Institutes of Health, 3Purdue University

Correspondence: *jtesmer@purdue.edu

This research was funded by: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (A.T.R.); the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Division of Preclinical Innovation (A.J.); American Heart Association 15POST24870001 and National Institutes of Health F32HL131288 (K.A.M.); American Heart Association 16POST27760002 (W.Y.); National Institutes of Health HL071818 and HL122416 (J.J.G.T.); and American Heart Association 13SDG17230049 (A.S.). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (Grant 085P1000817).

© 2018 eLife Sciences Publications Ltd.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.