By combining supramolecular chemistry and nanoparticle self-assembly, a team of researchers from from the University of Michigan, Myongji University (Japan), and Argonne has created a new toolbox of golden possibilities. Supramolecular chemistry is the study of how molecular bits hook up, the breaking and making of coordination complexes, in which an atom shares bonding electrons. Unlike these strong covalent bonds, nanoparticle self-assembly usually relies on weaker, reversible intermolecular forces that include electrostatic, van der Waals, hydrophobic, dipolar interactions, hydrogen bonds, and entropic forces. Science has had great successes with nanoscale engineering and control, but coordination bonds are stronger and can create more geometrically complex structures. What if supramolecular chemistry techniques were applied to nanoparticle assembly? The combination of coordination bonds and non-covalent reactions between particles could create new nanoparticle systems. Brilliant! Researchers in this study, working in part at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), examined the potential for nanoparticle assembly driven by the coordination of metal ions in a simple and familiar material: iron sulfide, or pyrite (FeS2). Despite pyrite’s history as a disappointing mimic of precious metal, this “fool’s gold” yields valuable results.

The researchers created disk-shaped wafers of pyrite, a few nanometers across, and stabilized them in thioglycolic acid, a small molecule of sulfur, oxygen, and carbon. They mixed these nanoparticles with ZnCl2(zinc chloride), which is known to dissociate Zn ions that happily bond with carbon and oxygen containing carboxylate groups. When they returned a day or so later, the researchers found that their ingredients had combined to form irregularly shaped nanoscale sheets, ten to several hundred times longer than the disks they started with.

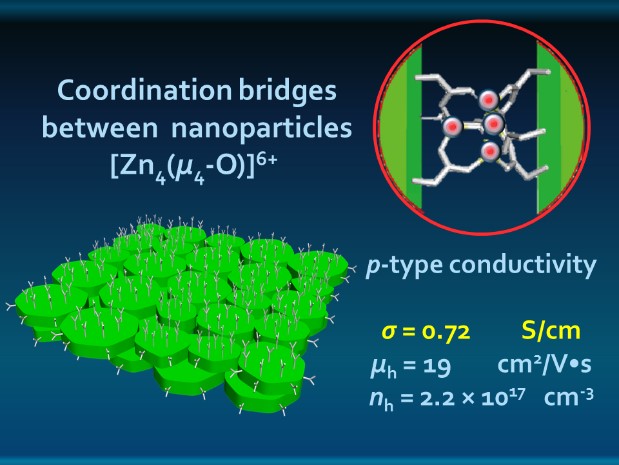

Electron microscopy helped the researchers determine what the sheets looked like and how they arranged themselves. Tests showed that the nanosheets were composed of iron, sulfur, and zinc, and indicated a Zn-carboxylate coordination. Electron microscopy combined with x-ray diffraction provided insight into material chemistry, composition, and structure. Synchrotron extended x-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy at the X-ray Science Division (XSD) 12-BM-B beamline at the Argonne APS, an Office of Science user facility, helped the researchers to establish the coordination pattern of the Zn ions and the geometry of the bridges that held the particles together and provided striking hole conductance through the sheets.

Electron diffraction data suggested that the planes of small disks oriented themselves parallel to the planes of nanosheets, stacked on top of each other in liquid-crystal-like orientation (like a tiny deck of cards, if the cards were sheets of tiny M&Ms). Synchrotron small-angle x-ray scattering, carried out at the XSD12-ID-B beamline, also at the APS, confirmed this data. The researchers had created sheets of FeS2 disks arranged edge-to-edge and held together with carboxylate coordination compounds (Fig. 1).

In other words, it worked!

The data indicated that the assembly of the nanosheets was driven by coordination bonds between the particles rather than weaker intermolecular forces. As an affirmation, the researchers broke down the Zn coordination bridges with the addition of a dissolving liquid, and recovered disk-like nanoparticles identical in size and shape to the originals.

While this achievement is nifty, the real value of this work is that it suggests so much more. Researchers could use this marriage of techniques with almost any compatible nanostructure, stabilizing ligand, coordination site, and metal ion. They can create new geometries with new combinations of materials.

Biological systems utilize coordination chemistry, as do coordination polymers and metal-organic frameworks. With similar techniques, researchers can combine nanoparticles and nanowires with these other powerful building blocks, almost as if suddenly every object in a house became Lego-compatible.

Now that they have the tools, it is likely that researchers will begin to tinker. This work should influence material-building for applications in electronics, catalysis, solar cells, energy storage, medicine, ion transport, gas phase chemistry, and more.

See: Kenji Hirai1, Bongjun Yeom1, 2, Shu-Hao Chang1, Hang Chi1, John F. Mansfield1, Byeongdu Lee3, Sungsik Lee3, Ctirad Uher1, and Nicholas A. Kotov1*, “Coordination Assembly of Discoid Nanoparticles,” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 8966 (2015). DOI: 10.1002/anie.201502057

Author affiliations: 1University of Michigan, 2Myongji University, 3Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: *kotov@umich.edu

The key parts of this work were supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) project “Energy- and Cost-Efficient Manufacturing Employing Nanoparticles” (NSF 1463474 to N.A.K.). Partial support was also made by the Center for Photonic and Multiscale Nanomaterials (CPHOM) funded by the NSF Materials Research Science and Engineering Center program DMR 1120923 as well as NSF projects 1403777 and 1411014. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.