The original University of California, San Diego press release by Liezel Labios can be read here

Why one particular cathode material works well at high voltages, while most other cathodes do not has been explained by research at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS). These insights, published in the June 19, 2015, issue of the journal Science, could help battery developers design rechargeable lithium-ion batteries that operate at higher voltages.

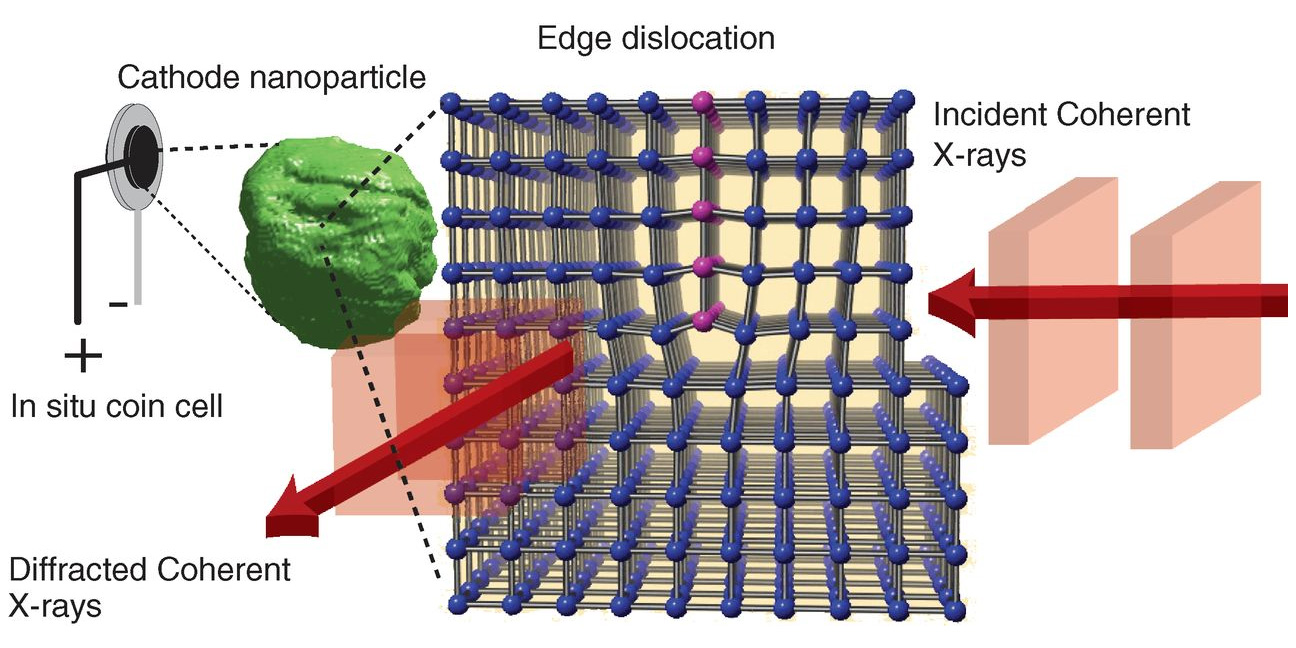

Researchers used a powerful x-ray imaging technique combined with new data analysis algorithms to gain insights — at the nanoscale level — on the mechanical properties of a cathode material called an LNMO spinel (composed of lithium, nickel, manganese, and oxygen atoms). The study reveals how the cathode material behaves while the battery charges and offers a possible explanation for why this particular cathode material works well at high voltage levels, an attribute that is crucial for batteries used in high-power applications such as electric cars.

In addition, the imaging and data analysis techniques described in this study provide new strategies for discovering how other cathode materials behave at the nanoscale level while batteries are charging.

The multi-institution team from the University of California, San Diego; the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, the Deutsches Elektronensynchrotron (DESY, Germany), and Argonne National Laboratory employed x-ray imaging experiments including Bragg coherent diffraction imaging at X-ray Science Division beamline 34-ID-C at the Argonne APS, which is an Office of Science user facility.

“Understanding why this cathode material works well at high voltage can help us understand how to make other battery materials also work better at high voltages,” said Andrew Ulvestad of UC San Diego, the first author of the Science paper.

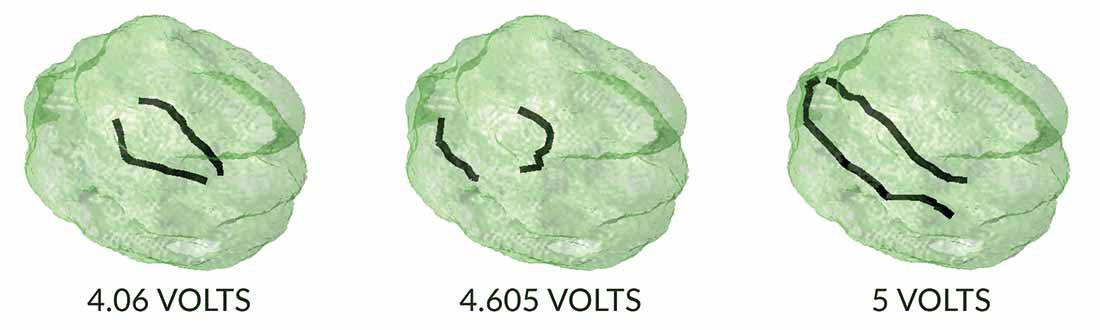

While the cathode materials in most of today’s lithium-ion batteries operate at 4.2 volts maximum, the LNMO spinel is robust at higher voltages — it functions at up to 4.9 volts. Reasons for why this material performs well at high voltages have remained a mystery. The team in this study has now offered an answer to this question. Through imaging and data analysis techniques, they identified and located defects within the cathode material. The defects are irregularities in the material’s otherwise highly ordered atomic structure.

Using the APS, the team imaged the cathode material while it was inside a charging lithium-ion battery. Analyses of the images revealed that the defects are stationary when the battery is at rest. But when the battery is charged to high voltage, the defects move around within the cathode material. The researchers report that this is a significant finding because it shows that the material has a unique way of responding to the strain that is induced at high voltage.

“Materials typically respond to strain by cracking. Our experiments show that this material handles strain by moving the defects around while the battery is charging,” said Shirley Meng of UC San Dieg, a corresponding author on the Science paper. “From the perspective of a battery materials researcher, this study also points to the exciting possibility of ‘defect engineering’ for battery materials. This would involve designing new battery materials that have specific ‘defects’ that improve performance.”

“Defects have a bad reputation due to our constant drive towards perfection,” said Oleg Shpyrko of UC San Diego, also a corresponding author on the study. “But can we use a defect-engineering approach to design and create new types of materials, or perhaps to enhance the desirable properties of the existing ones? Our research shows that the defects can be directed, or even choreographed, by simply running an electric current through the material.”

Bragg coherent diffractive imaging uses laser-like X-ray beams and novel computer algorithms to reconstruct high-resolution three-dimensional (3-D) images of nanoscale structures, such as the LNMO spinel described in this study.

Defects are difficult to image directly because they are extremely small — less than a nanometer in size. However, each defect causes a strain field, which is an area of deformation surrounding the defect in the atomic structure. The strain fields are much larger — tens of nanometers in size — making them large enough to be imaged. By analyzing the strain fields in the LNMO spinel, the team mapped out the defects and studied how they play a role in the material’s performance at high voltage.

“These new imaging methods that allow us to look inside the battery — while it is operating in real time — will be important not only for energy storage materials, but also for many other applications, novel materials and devices,” said Shpyrko. “Thanks to our combined efforts, we have developed the suite of tools that can help unravel the complexities of atomic-scale defects, which are commonly associated with performance degradation, but can also potentially be used to control or optimize the material’s properties.”

“It’s important to see the defects and know where they are in order to understand how they might change the properties of the material,” said Ulvestad. “We are the first to do this imaging in a working battery.”

The team used the defects to probe the mechanical properties of the LNMO spinel. The researchers report that the movement of the defects while the battery is charging causes changes in the strain fields, which are described by mathematical equations. Using these equations, the team calculated a material property called the Poisson’s ratio and discovered that this value is negative when the material is charged to higher voltages.

The Poisson’s ratio expresses how a material behaves under an applied strain. Most materials have a positive Poisson’s ratio. This means when a material is enlarged in one dimension, it shrinks in the other two dimensions, and vice versa. For example, stretching a rubber band in one dimension makes it thinner in the other dimensions, while pressing down on a ball in the vertical dimension makes it expand in the horizontal dimensions.

Materials with a negative Poisson’s ratio behave the opposite under an applied strain. If a rubber band had a negative Poisson’s ratio, stretching it in one dimension would make it fatter (instead of thinner) in the other dimensions. Materials that behave this way are rare.

A negative Poisson’s ratio has important applications for lithium-ion battery materials. It enables materials to maintain their shape regardless of what type of strain is applied, making them more tolerant to strain.

“The LNMO spinel is incredibly strong. You can expand it or shrink it, and it doesn’t crack. No one has ever reported a negative Poisson’s ratio in battery materials. We hypothesize that this property helps make this cathode material more resistant to strain than other materials at high voltages,” said Meng.

The proposed APS Upgrade will be a complete game changer for these types of studies. The increased time and spatial resolution will allow one to investigate how and why defects move through a lattice, not just that they do.

See: A. Ulvestad1, A. Singer1, J.N. Clark2,3, H.M. Cho1, J. W. Kim1, R. Harder4, J. Maser4, Y.S. Meng1,* O. G. Shpyrko1**, “Topological defect dynamics in operando battery nanoparticles,” Science 348(6241), 1344 (19 June 2015). DOI: 10.1126/science.aaa1313

Author affiliations: 1University of California, San Diego; 2SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory; 3Deutsches Elektronensynchrotron (DESY); 4Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: *shmeng@ucsd.edu, **oshpyrko@physics.ucsd.edu

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences, under contract DE-SC0001805. H.M.C. and Y.S.M. acknowledge support on the in situ CXDI cell design, materials synthesis, and electrochemical and materials characterization from the NorthEast Center for Chemical Energy Storage, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. DOE Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences under Award no. DE-SC0012583. O.G.S. and Y.S.M. are grateful to the University of California, San Diego, Chancellor’s Interdisciplinary Collaborators Award that made this collaboration possible. J.N.C. gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Volkswagen Foundation. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.