The original Caltech press release by Whitney Clavin can be read here.

In a new study published in Nature Communications, a team of researchers from Caltech reports the first atomic-scale look at the specific components of human nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) responsible for dropping mRNAs off in the cytoplasm. These new results are based upon research carried out at three U.S. Department of Energy synchrotron light source research facilities, including the Advanced Photon Source (APS).

Standing guard between a cell's nucleus and its main chamber, called the cytoplasm, are thousands of behemoth protein structures called nuclear pore complexes. NPCs are like the bouncers of a cell's nucleus, tightly guarding exactly what goes in and out. Each structure contains about 1,000 protein molecules, making NPCs some of the biggest protein complexes in our bodies. One of the most notable clients of NPCs is a class of molecules known as messenger RNAs, or mRNAs. These are the messengers that carry genetic instructions from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where they are then translated into proteins.

But how the NPC transports the mRNAs out of the nucleus is still a mystery.

"The mRNAs are one of the largest cargoes carried through NPCs, and the whole process occurs in just a fraction of a second," said André Hoelz, professor of chemistry at Caltech, a Heritage Medical Research Institute (HMRI) Investigator, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Faculty Scholar. "How this works has been one of the greatest unsolved problems in biology." The study, which was carried out by Hoelz and his Caltech research team, was spearheaded by Daniel Lin, a former graduate student at Caltech now at Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research at MIT, and Sarah Cai, an undergraduate student at Caltech.

NPCs are associated with several diseases. Mutations to proteins within the complex have been linked to motor neuron diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and people with Huntington's disease are known to have defects in the function of their NPCs.

For an mRNA to be transported through an NPC, it must be tagged with a nuclear export factor, a type of small protein. That tag is like a ticket that allows the mRNA to enter the central transport channel of the NPC. Once the mRNA reaches the cytoplasmic side, it must surrender the ticket—otherwise, the mRNA could travel back into the nucleus, and the proteins it encodes wouldn't get made.

Through a series of experiments involving x-ray crystallography, biochemistry, enzymology, and other methodologies, the researchers were able to show how this process of un-tagging the mRNA molecules works in human cells for the first time.

"It's as if we had snapshots before, and now we have a movie showing us exactly what happens at the molecular scale when mRNAs are dropped off in the cell's cytoplasm," said Lin.

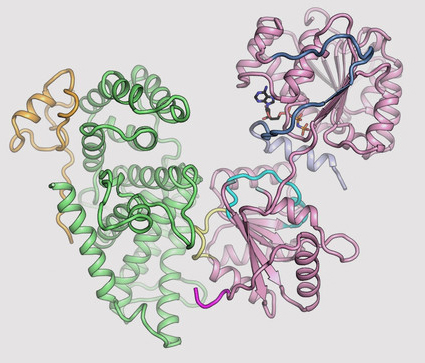

The team's new findings were made possible by obtaining a series of x-ray diffraction-based crystal structures of a few key protein components of a human NPC. These structures were determined at 2.2, 2.65, 2.8, and 3.6 Å resolution at the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and National Cancer Institute (GM/CA-XSD) 23-ID-D beamline at the APS at Argonne National Laboratory; 1.75 Å resolution at beamline 12-2 of the Stanford Synchotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory; and 3.4 Å resolution at the Frontier Microfocusing Macromolecular Crystallography beamline (FMX) at the National Synchotron Lightsource-II (NSLS-II) at Brookhaven National Laboratory. The APS, SSRL, and NSLS-II are all Office of Science user facilities. The authors note that the state-of-the-art microfocusing abilities at all three of these specific beamlines was critical to solving these structures.

One of those components is called Gle1. The three-dimensional structure of this protein had been obtained before in yeast, but doing so for its human variant had remained a challenge. By studying the biochemical properties of yeast Gle1, the researchers were able to figure out that another protein, called Nup42, was required to stabilize Gle1. Knowing this, the team was able to purify human Gle1 from cells in high quantities for the first time, and then, using Caltech's Molecular Observatory beamline at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, obtain its crystal structure.

"Even with billions of years of evolution between yeast and humans, there are still aspects of our bio-machinery that remain the same," says Lin.

With the ability to purify human Gle1, the researchers set about studying how mutations affect its structure. They looked at several specific mutations of Gle1 known to be associated with a motor neuron disease called lethal contracture congenital syndrome 1 (LCCS1) and discovered that the mutated versions of the protein were not as stable.

"Gle1 is essential for life to function properly," says Hoelz, "so any mutations that cause it to be less stable are going to cause problems."

The researchers then looked at the structure of Gle1 bound to a protein called DDX19—which is responsible for un-tagging the mRNA molecules after they pass through the NPC. Gle1 is required to activate DDX19, and—until now—it was thought that a small molecule called inositol hexaphosphate (IP6) acted like a tether between Gle1 and DDX19, allowing the activation to occur.

"We found that IP6 was not required in humans, and that was a surprise because it is required in yeast, and IP6 dependence was previously believed to occur across all species," says Cai. "While there are some similarities between yeast and human proteins, there are also crucial differences."

What's more, the new research shows in atomic-level detail exactly how the un-tagging of the mRNA works. This kind of structural information could be used in the future to help in the design of therapeutic drugs for motor neuron diseases.

Hoelz says that Lin and Cai really exceeded expectations. "They wanted to discover something new, and they went above and beyond with this project," he says. "They made it happen."

See: Daniel H. Lin, Ana R. Correia, Sarah W. Cai, Ferdinand M. Huber, Claudia A. Jette, and André Hoelz, “Structural and functional analysis of mRNA export regulation by the nuclear pore complex,” Nat. Commun. 9, 2319 (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-04459-3

Author affiliation: California Institute of Technology

Correspondence: *hoelz@caltech.edu

We thank Alina Patke for critical reading of the manuscript, Karsten Thierbach for advice on yeast experiments, and Susan Wente for helpful discussions and sharing data prior to publication. We also acknowledge Jens Kaiser and the scientific staffs of SSRL Beamline 12-2, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and National Cancer Institute Structural Biology Facility (GM/CA) at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), and the Frontier Microfocusing Macromolecular Crystallography (FMX) beamline at the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II) for support with x-ray diffraction measurements.

The authors acknowledge the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Beckman Institute, and the Sanofi-Aventis Bioengineering Research Program for their support of the Molecular Observatory at the California Institute of Technology. GM/CA-XSD has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (grant ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant AGM-12006). The crystal structure of ctGle1CTD•Nup42CTDCTD•IP6 was determined at the CCP4/APS School for Macromolecular Crystallography (2016), which was supported by the National Cancer Institute (AGM-12006) and the National Institute of General Medical Science (ACB-12002).

D.H.L. and C.A.J. were supported by an National Institutes of Health Research Service Award (5 T32 GM07616). D.H.L. and F.M.H. were supported by an Amgen Graduate Fellowship through the Caltech-Amgen Research Collaboration. S.W.C. was supported by a Margaret Leighton Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship and a John Stauffer Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship through the Caltech Student-Faculty Programs Office. A.H. is a Faculty Scholar of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and an Investigator of the Heritage Medical Research Institute. A.H. was also supported by NIH grant R01-GM117360, Caltech startup funds, and a Teacher-Scholar Award of the Camille & Henry Dreyfus Foundation. Use of the SSRL, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393). This research used resources of the National Synchrotron Light Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-98CH10886. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.