The original Saint Louis University press release by Carrie Bebermeyer can be read here.

The structure of a key protein that is involved in the body's inflammatory response has been solved by researchers working at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS). This finding opens the door to developing new treatments for a wide range of illnesses, from heart disease, diabetes, and cancer to neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinson's disease. The paper describing the study was published in Nature Communications.

Sergey Korolev, Ph.D., associate professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at Saint Louis University (SLU), studies protein structures at the atomic resolution level to understand mechanism of their function in the body. Korolev and his colleagues from SLU, Argonne National Laboratory, and the Washington University School of Medicine, utilized the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and National Cancer Institute (GM/CA-XSD) structural biology facility x-ray beamlines 23-ID-B and 23-ID-D at the APS to examine a long-studied but little-understood enzyme, calcium-independent phospholipase A2β, (iPLA2β) that cleaves phospholipids in membrane. It produces important signals after injury to initiate the inflammatory response. The team wanted to know how the enzyme is activated during injury, how it hydrolyses substrates and how it gets shut down, turning the inflammatory response off. (The APS is an Office of Science user facility at Argonne.)

Korolev says that the protein kept popping up in seemingly unrelated areas of study throughout the last few decades.

"It was first discovered more than 20 years ago at Washington University in Richard Gross's lab," Korolev said. "They found that the protein played a role as a part of the cardiovascular system in response to an ischemia or injury.

"Next, researchers found that it is also involved in the insulin production cycle and, when mis-regulated, can lead to type I diabetes. Then, less than 10 years ago, it was rediscovered from a completely different point of view through the genetic sequencing of patients with neurodegenerative issues. For example, inherited mutations in this gene were identified in patients with early onset Parkinson's."

For this reason, the protein also has a second name, PARK14, due to numerous inherited mutations of this gene that were identified in patients with early Parkinson's.

Researchers saw that the protein played different roles in different tissues and parts of the cell. The protein's changeable roles added to difficulties in understanding how it operated.

It was clear to scientists, though, that the action of the protein can be harmful, contributing to cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer metastasis, and many investigators attempted to design inhibitors to serve as potential new therapies.

"Different groups tried to design inhibitors, but it was very difficult without knowing the 3D structure of the protein," Korolev said.

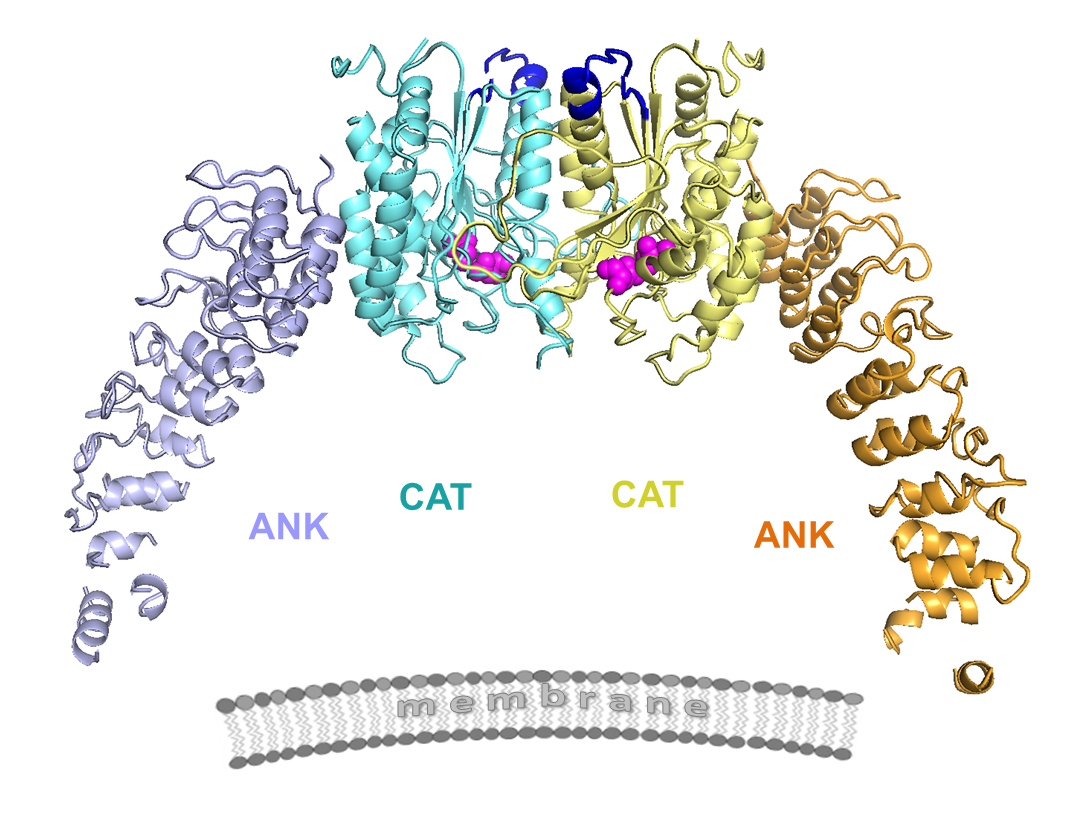

In order to learn more about the protein, SLU researchers used x-ray macromolecular crystallography at the GM/CA-XSD facility to collect diffraction images of the protein structure at 3.9-angstrom resolution (Fig. 1). The process involves growing a crystal of the protein, shooting x-ray beams through the crystal and analyzing the diffraction pattern generated on a detector plate in order to detail the three-dimensional structure of the protein. Often, the most difficult part of the process protein crystallization, which can take years to achieve.

With his team's success in discovering the protein's structure, Korolev anticipates that the door has been opened to answer many more questions about the protein. "Before we had the structure, people didn't have good tools to study this enzyme," Korolev said. "Now, this will take the field to a new level.

"We've opened up lots of possibilities. The mechanism of regulation was completely unknown. Now, the 3-D structure gives us a clear hypothesis for how it is responsible for action in different cellular compartments and tissues. Now that we can better understand how the protein interacts with lipid molecules, it will be much easier to develop drugs."

Korolev notes that the structure his team discovered was quite different from what researchers predicted the protein might look like.

"One of the key findings about the structure we uncovered is that it significantly revised previously developed theoretical models,” he said, “which couldn't explain many functional features. Now, with the real structure, many pieces of an intricate puzzle click together providing clear hypothesis about the mechanism of protein's function and regulation."

In addition, Korolev is intrigued by the protein's function in the brain, which is completely unknown. Thanks to genetic sequencing, researchers can now map out which parts of a protein cause diseases. Having the genetic information together with the three-dimensional structure will offer researchers a powerful new tool.

"This has been a long project," Korolev said. "It turned out that this enzyme was difficult to work with. It was challenging to get funding. Our collaborators dropped out. We were supported for a long time with a low budget because the department kept us afloat. SLU undergrads helped us. We received some funding from NASA to try crystallization under microgravity conditions and a small NIH grant. Most recently, our M.D./Ph.D. student, Konstantin Malley, who authored the paper, worked really hard on this research.

"In the past, people have studied this complex enzyme, like a black box, without knowing what is inside," Korolev said. “Now that we have discovered the structure, we can see every atom. This allows us to visualize what is happening with this protein. It is a completely new level of insight."

Malley hopes the findings will prove to be a helpful step forward in the development of new therapies for neurodegenerative disease. "There is a growing amount of genetic work that links iPLA2β to neurodegenerative disease, and physicians and scientists worldwide are now interested in its function," Malley said. "We are still a long way from treating patients, but I would like them to know that the structure is a large step between genetics and developing targeted therapies for treatment.

"We hope that it provides a jumping-off point for firstly, understanding how iPLA2β works in the brain. Next we can employ different strategies, such as small molecule drugs, that would either prevent iPLA2β interacting with other proteins, or change its activity to prevent inflammation, which is an increasingly important factor in Parkinson's and other brain disorders."

See: Konstantin R. Malley1, Olga Koroleva1, Ian Miller1, Ruslan Sanishvili2, Christopher M. Jenkins3, Richard W. Gross3,4, and Sergey Korolev1*, “The structure of iPLA2β reveals dimeric active sites and suggests mechanisms of regulation and localization,” Nat. Commun. 9, 765 (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-03193-0

Author affiliations: 1Saint Louis University School of Medicine, 2Argonne National Laboratory, 3Washington University School of Medicine, 4Washington University

Correspondence: *sergey.korolev@health.slu.edu

GM/CA-XSD beamlines 23-ID-B and 23-ID-D are funded in whole or in part from the National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM-12006). This research was supported by the American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid #0665513Z, Center for Advancement of Science in Space (CASIS) grant CASIS-2012-1, NIH/NINDS grant R21NS094854 (to S.K.) and NIH/NHLBI grant R01HL118639 (to R. W.G.). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.