The original Scripps Research Institute press release can be read here.

As co-leaders of an international collaboration that carried out research at two U.S. Department of Energy synchrotron x-ray user facilities, scientists from Scripps Research have discovered that tethering four antibodies together may be an effective strategy for neutralizing all types of influenza virus known to infect humans. The research, published in Science, suggests this strategy could lead to influenza prevention tools with the strength and potency to last throughout the flu season, even as the virus mutates rapidly.

"We don't have a vaccine yet that protects against all of the two main types of influenza (A and B). The key to this study is the engineering of a multidomain antibody that is cross-neutralizing to influenza A and B," said Ian Wilson of Scripps Research and a lead author of the study.

Tethering together antibodies is not a new concept, but this is the first time four antibodies have been tethered together and tried against influenza.

The antibodies in this study came from llamas that had been challenged with a vaccine containing three types of the virus, as well as a key protein from two different strains of influenza. Llamas are important in immunology research because they produce unique antibodies that are smaller and simpler than those found in humans and can fit into smaller and more recessed binding sites on the viral surface.

"In this case, the llama antibodies could be linked together to create multi-specific antibodies binding to different sites on different targets," Wilson said. "This multi-specificity is the key to having broad coverage of highly variable pathogens like influenza."

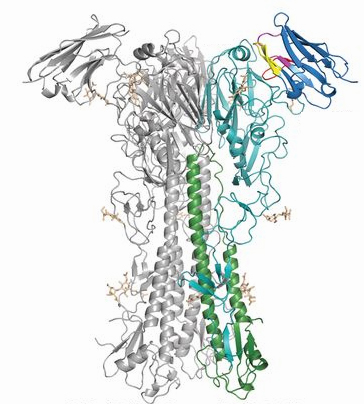

The scientists tethered together two llama antibodies against influenza A and two against influenza B to create a "multidomain" antibody. With their Scripps Research colleagues, Wilson and Andrew Ward led the x-ray and electron microscopy structural studies to show exactly where this multidomain antibody was binding to influenza proteins. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and National Cancer Institute x-ray beamlines 23-ID-B and 23ID-D at the Advanced Photon Source, at the Industrial Macromolecular Crystallography Association Collaborative Access Team beamline 17-ID-B also at the APS, and at beamline BL12-2 of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource. (The Advanced Photon Source is an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory. The Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource is an Office of Science user facility at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.)

The Scripps team found that the multidomain antibody could target key vulnerable sites on influenza A and B. This enabled the antibody to be cross-reactive and may have the ability to protect against all circulating strains of the virus that affect humans, as well as new subtypes that could mutate to cause pandemics.

"The question then was how you might deliver those antibodies," said Wilson.

For this, the scientists turned to an approach traditionally used in gene therapy, not vaccine design. They used a viral vector that could deliver a specially engineered gene to instruct cells to start expressing a producing protein comprised of fragments from all four llama antibodies.

The viral vector, called adenovirus-associated virus, was then administered into the nostrils of mice via a nasal spray. The goal was to get them to produce these protective antibodies in their upper respiratory tract, the tissues most vulnerable to influenza.

Collaborators at the University of Pennsylvania, led by James Wilson, and Maria Limberis, found that this approach could offer protection against multiple strains of influenza — and it worked rapidly, within a few days in most of the mice.

While the study suggests that a multidomain antibody approach may hold potential as a strategy for the prevention of influenza A and B, this research is preclinical and further study is required to determine whether such a medicine can successfully be developed.

See: Nick S. Laursen1‡, Robert H. E. Friesen2‡‡, Xueyong Zhu1, Mandy Jongeneelen3, Sven Blokland3, Jan Vermond4, Alida van Eijgen4, Chan Tang3, Harry van Diepen4, Galina Obmolova2, Marijn van der Neut Kolfschoten3, David Zuijdgeest3, Roel Straetemans5, Ryan M. B. Hoffman1, Travis Nieusma1, Jesper Pallesen1, Hannah L. Turner1, Steffen M. Bernard1, Andrew B. Ward1, Jinquan Luo2, Leo L. M. Poon6, Anna P. Tretiakova7‡‡‡, James M. Wilson7, Maria P. Limberis7, Ronald Vogels3, Boerries Brandenburg3, Joost A. Kolkman8**, Ian A. Wilson1*, “Universal protection against influenza infection by a multidomain antibody to influenza hemagglutinin,” Science 362, 598 (2018). DOI: 10.1126/science.aaq0620

Author affiliations: 1The Scripps Research Institute, 2Janssen Research and Development, 3Janssen Vaccines and Prevention, 4Janssen Prevention Center, 5Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson and Johnson, 6The University of Hong Kong, 7University of Pennsylvania, 8Janssen Infectious Diseases ‡Present address: Aarhus University ‡‡Present address: Ablynx, ‡‡‡Present address: Pfizer

Correspondence: * wilson@scripps.edu, ** jkolkman@its.jnj.com

This work is supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R56 AI117675 and R56 AI127371 (to I.A.W.), by a grant from Janssen, and in part by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, Department of Defense (grant 64047-LS-DRP.02 to J.M.W.), and the Theme-based Research Scheme, Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong (ref. T11-705/14N). The General Medical Sciences and National Cancer Institute facility is funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM-12006); the Eiger 16M detector was funded by an NIH–Office of Research Infrastructure Programs, High-End Instrumentation Grant (1S10OD012289-01A1). Use of the Industrial Macromolecular Crystallography Association Collaborative Access Team beamline was supported by the companies of the Industrial Macromolecular Crystallography Association through a contract with Hauptman-Woodward Medical Research Institute. Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences under contract DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the NIGMS (including P41GM103393). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.