The original MIT press release by Anne Trafton can be read here.

Many microbes have an enzyme that can convert carbon dioxide to carbon monoxide. This reaction is critical for building carbon compounds and generating energy, particularly for bacteria that live in oxygen-free environments. This enzyme is also of great interest to researchers who want to find new ways to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere and turn them into useful carbon-containing compounds. Current industrial methods for transforming carbon dioxide are very energy-intensive.

“There are industrial processes that do these reactions at high temperatures and high pressures, and then there’s this enzyme that can do the same thing at room temperature,” said Catherine Drennan, an MIT professor of chemistry and biology and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. “For a long time, people have been interested in understanding how nature performs this challenging chemistry with this assembly of metals.”

Drennan and her colleagues at MIT, Brandeis University, Aix-Marseille University (France), and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research have now discovered a unique aspect of the structure of the “C-cluster” — the collection of metal and sulfur atoms that forms the heart of the enzyme carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH). Instead of forming a rigid scaffold, as had been expected, the cluster can actually change its configuration.

“It was not what we expected to see,” said Elizabeth Wittenborn, a recent MIT Ph.D. recipient and the lead author of the study, which appeared in the journal eLife.

Metal-containing clusters such as the C-cluster perform many other critical reactions in microbes, including splitting nitrogen gas, that are difficult to replicate industrially.

Drennan began studying the structure of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase and the C-cluster about 20 years ago, soon after she started her lab at MIT. She and another research group each came up with a structure for the enzyme using x-ray crystallography, in part at the BioCARS structural biology facility at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), but the structures weren’t quite the same. The differences were eventually resolved and the structure of CODH was thought to be well-established. (The APS is an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory.)

Wittenborn took up the project a few years ago, in hopes of nailing down why the enzyme is so sensitive to inactivation by oxygen and determining how the C-cluster gets put together.

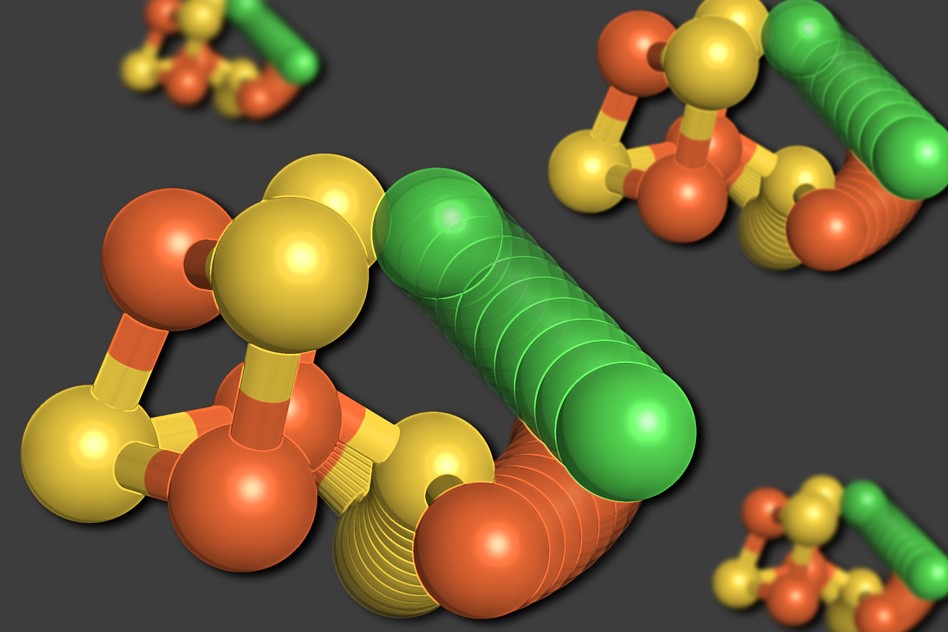

To the researchers’ surprise, their analysis of new x-ray data collected at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team 24-ID-C x-ray beamline at the APS revealed two distinct structures for the C-cluster. The first was an arrangement they had expected to see — a cube consisting of four sulfur atoms, three iron atoms, and a nickel atom, with a fourth iron atom connected to the cube.

In the second structure, however, the nickel atom is removed from the cube-like structure and takes the place of the fourth iron atom. The displaced iron atom binds to a nearby amino acid, cysteine, which holds it in its new location. One of the sulfur atoms also moves out of the cube. All of these movements appear to occur in unison, in a movement the researchers describe as a “molecular cartwheel.”

“The sulfur, the iron, and the nickel all move to new locations,” Drennan said. “We were really shocked. We thought we understood this enzyme, but we found it is doing this unbelievably dramatic movement that we never anticipated. Then we came up with more evidence that this is actually something that’s relevant and important — it’s not just a fluke thing but part of the design of this cluster.”

The researchers believe that this movement, which occurs upon oxygen exposure, helps to protect the cluster from completely and irreversibly falling apart in response to oxygen.

“It seems like this is a safety net, allowing the metals to get moved to locations where they’re more secure on the protein,” Drennan said.

Douglas Rees, a professor of chemistry at Caltech, described the paper as “a beautiful study of a fascinating cluster conversion process.”

“These clusters have mineral-like features and it might be thought they would be ‘as stable as a rock,’” said Rees, who was not involved in the research. “Instead, the clusters can be dynamic, which confers upon them properties that are critical to their function in a biological setting.”

This is the largest metal shift that has ever been seen in any enzyme cluster, but smaller-scale rearrangements have been seen in some others, including a metal cluster found in the enzyme nitrogenase, which converts nitrogen gas to ammonia.

“In the past, people thought of these clusters as really being these rigid scaffolds, but just within the last few years there’s more and more evidence coming up that they’re not really rigid,” Drennan said.

The researchers are now trying to figure out how cells assemble these clusters. Learning more about how these clusters work, how they are assembled, and how they are affected by oxygen could help scientists who are trying to copy their action for industrial use, Drennan said. There is a great deal of interest in coming up with ways to combat greenhouse gas accumulation by, for example, converting carbon dioxide to carbon monoxide and then to acetate, which can be used as a building block for many kinds of useful carbon-containing compounds.

“It’s more complicated than people thought. If we understand it, then we have a much better chance of really mimicking the biological system,” Drennan said.

See: Elizabeth C Wittenborn1, Mériem Merrouch2, Chie Ueda3, Laura Fradale2, Christophe Léger2, Vincent Fourmond2, Maria-Eirini Pandelia3, Sébastien Dementin2*, and Catherine L Drennan1,4,5**, “Redox-dependent rearrangements of the NiFeS cluster of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase,” eLife 7, e39451 (2018). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.39451

1Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2Aix Marseille University, 3Brandeis University, 4Howard Hughes Medical Institute, 5Canadian Institute for Advanced Research

Correspondence: *dementin@imm.cnrs.fr, **cdrennan@mit.edu

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants T32 GM008334 (ECW), R01 GM069857 and R35 GM126982 (CLD), and R00 GM111978 (M-EP); and ANR projects MeCO2Bio and SHIELDS. C.L.D. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator and a senior fellow of the Bio-inspired Solar Energy Program, Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. The Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines are funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences from the NIH (P41 GM103403). The Pilatus 6M detector on beamline 24-ID-C is funded by a NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Pro-grams High End Instrumentation grant (S10 RR029205). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.