Slowly flapping its orange and black wings, a monarch butterfly sips liquid from a patch of mud. Its proboscis – the mouthpart that sucks up liquids – grazes the damp soil. For years, biologists knew that butterflies drew liquids up from surfaces with pores differently than they do from flowers. But they had no way to observe those differences.

"The biologists knew of this feeding mode, but didn't have tools to observe what was going on," said Daria Monaenkova, who studied this behavior as a graduate student at Clemson University.

Microscopes alone couldn't reveal what Monaenkova wanted to study. But a relatively new technique using an extremely powerful X-ray turned out to be just the thing. Using the DOE's Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory, Monaenkova and other researchers have been able to take high-resolution videos of the insides of living insects.

For the past decade, the APS has been a home for scientists specializing in insect biomechanics to do research they can do nowhere else. Scientists studying butterflies, mosquitoes, and beetles have used the APS to reveal new insights into how they function and potentially inspire technology based on those functions.

Real-Life X-Ray Vision

Scientists who study insects need tools that can look through their hard external skeletons, reveal features of soft tissue, record movements that are a thousandth of a second long, and show details that are one millionth of a meter long. Most of all, they need to capture how these systems work in real time. Regular microscopes can't fulfill many of these needs.

But synchrotron X-rays, which are produced by particle accelerators, can. Just as doctors use X-rays to look inside human bodies, scientists can use them to look inside insect bodies. X-rays are especially useful for taking images of structures that have different densities, like mouthparts and digestive systems.

Not just any X-ray will do. Scientists can't control regular X-ray beams enough to conduct these experiments. But the Office of Science's user facility light sources produce extraordinarily powerful X-rays that provide scientists with very fine control. In the case of the APS, it's enough control to look inside an insect without vaporizing it.

These X-rays move into experimental stations where scientists run studies. Each APS beamline has X-ray optics that can select the X-ray's energy and focus it to the station to meet scientists' needs. The X-rays move through the object being studied and go into a scintillator — a specialized crystal that transforms X-rays into visible light. A high-end camera captures that visible light on video.

"It's like a whole new world revealed," said Jake Socha, biomechanical engineering professor at Virginia Tech. "Almost anything you can put into the beam, you're seeing that perspective new for the first time."

Even for the people who specialize in X-ray machines, the clarity of the images is surprising. Wah-Keat Lee, an X-ray researcher who was at the APS and is now at the NSLS-II, a different Office of Science user facility, pioneered the technique. Describing the first time he saw the results, he said, "The clarity of the internal structures of the small insect was quite phenomenal."

The APS achieves this clarity with a very intense, high-energy, tight beam that also has high brilliance (the amount of light it can focus on a particular place at a particular time). Like a camera with a high-shutter speed that requires a lot of light, brilliance is important for capturing extremely fast motion. In one experiment, scientists captured X-ray video at a rate of more than 10,000 frames per second. Movies at commercial theaters are typically 24 frames per second.

"The light sources still have a massive advantage in speed," said Socha, comparing them to other imaging technologies.

Most importantly, light sources can do phase-contrast imaging. Normal X-ray machines rely on the fact that dense objects — like bone — absorb a lot of X-rays. Those X-rays don't reach the detector and sections of the image come out dark. But insects don't have anything as dense as bone. As a result, their bodies absorb fewer X-rays and won't produce a sharp image. Phase-contrast X-ray imaging solves this problem. Even though light objects don't absorb many X-rays, they do change their waves. Because phase-contrast detectors can measure those changes, they're more sensitive to slight differences in density than traditional machines. In fact, using images from the APS, scientists could distinguish between fluids and air in an insect's food canal.

"It takes you from a fuzzy picture of a blob to a really sharp picture of an insect," said Socha.

Examining Inner Workings of Insects

While scientists studying inanimate objects at light sources have to deal with a number of challenges, at least they don't have to worry about them flying away.

Before they can deal with the insects themselves, researchers must decide on the machine's settings that result in the best images and least harm to the insects. The longer the X-ray's wavelength, the better the contrast. Similarly, the more intense the beam, the brighter and clearer the image. But the longer the wavelength and the more intense the beam, the more the X-ray damages the insect. This damage can make the insect act unnaturally or kill them. (While scientists often kill the bugs after the study is finished, they don't want them to die partway through.)

An early study that tested a variety of insects found that while five minutes under the beam didn't seem to have a negative effect on most species, more than 20 minutes temporarily paralyzed them. Even with that previous research, teams still spend their first six to eight hours at the APS deciding on their experiment's settings.

found that while five minutes under the beam didn't seem to have a negative effect on most species, more than 20 minutes temporarily paralyzed them. Even with that previous research, teams still spend their first six to eight hours at the APS deciding on their experiment's settings.

"There's a lot of trial and error. You're not going to go in there within a half-hour of set up and start collecting data," said Matthew Lehnert, an entomologist at Kent State University.

The next challenge involves keeping their flying and crawling subjects still.

"You can't just sit something in front of a beam and say, ‘Don't move,'" said Lehnert.

After knocking out the insects using nitrogen gas or by chilling them, scientists use surprisingly low-tech techniques to fasten them to platforms. Some researchers pin them down or surround them with cotton or modeling clay. Scientists studying mosquitoes attached them to the surface with nail polish. The paper even quotes the brand, for other researchers hoping to reproduce the work.

"Nail polish is a great tool for the lab," said Socha.

Next up is motivating insects to perform the desired behavior. For butterflies and mosquitoes, researchers wanted to observe their feeding habits. But normal sugar solution won't show up on the X-ray. The scientists worked with APS staff members to choose a form of iodine they could mix into the sugar solution that would both create a clear image and butterflies would be willing to eat.

With bombardier beetles, the scientists wanted to understand how they can create, heat, and shoot a liquid spray at temperatures close to boiling. But beetles don't spray on command. Some sprayed as soon as they woke up, startled by the fact there was an X-ray blasting them. With others, the scientists had to poke them with a pin.

While the process isn't pleasant for individual insects, what scientists learn can help them better understand the entire species and its evolution as a whole.

Butterflies and Beetles and Mosquitoes, Oh My

The resulting images made the experimentation worth it.

For butterflies, Monaenkova and her colleagues discovered that the proboscis acts like a combination of a sponge and a straw . The sponge-like structure at the tip of the proboscis creates capillary action, the ability of liquids to flow upwards without a sucking force. That helps the butterflies start the process of taking up liquid from porous materials, small droplets, and puddles. A mechanism in the butterfly's head then pumps the liquid up through the straw-like part of the proboscis.

. The sponge-like structure at the tip of the proboscis creates capillary action, the ability of liquids to flow upwards without a sucking force. That helps the butterflies start the process of taking up liquid from porous materials, small droplets, and puddles. A mechanism in the butterfly's head then pumps the liquid up through the straw-like part of the proboscis.

"Without this tool, the research we did would not be possible," said Monaenkova.

This discovery could help scientists develop new technology for tools that capture liquids or deliver medicine into people's bodies.

In the case of mosquitoes, researchers also found a new mode of feeding . Mosquitoes' heads have two different pumps that suck up liquid. By looking at which parts had food in them at any one time, scientists figured out how much each pump contributed to the overall flow. They found a new mode of sucking that's 27 times more powerful than the regular one. Further research in this area may help scientists better understand how mosquitoes transmit illnesses like the Zika virus.

. Mosquitoes' heads have two different pumps that suck up liquid. By looking at which parts had food in them at any one time, scientists figured out how much each pump contributed to the overall flow. They found a new mode of sucking that's 27 times more powerful than the regular one. Further research in this area may help scientists better understand how mosquitoes transmit illnesses like the Zika virus.

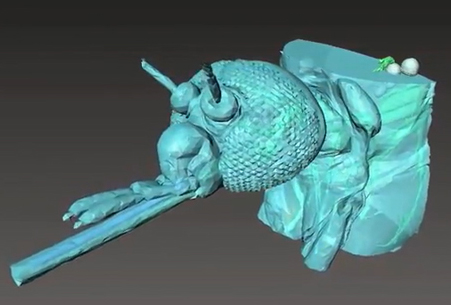

The scientists from Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Arizona studying bombardier beetles wanted to track each stage of the chemical reaction

that leads to the beetles' spray. Mapping how the vapor formed, expanded, and moved helped them understand how the beetle's body controls the process.

In every case, the APS revealed mechanisms that scientists had no other way of researching.

As Lee said, "The work we did here actually changed textbooks."

This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information please visit https://science.energy.gov.

Shannon Brescher Shea is a senior writer/editor in the Office of Science, shannon.shea@science.doe.gov