The original Scripps Research Institute press release can be read here.

About half of all drugs, ranging from morphine to penicillin, come from compounds that are from—or have been derived from—nature. This includes many cancer drugs, which are toxic enough to kill cancer cells. So how do the organisms that make these toxic substances protect themselves from the harmful effects? A team of researchers led by scientists from the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute in collaboration with Argonne researchers from the Midwest Center for Structural Genomics used extreme-brightness synchrotron x-rays from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) to uncover a previously unknown mechanism—proteins that cells use to bind to a toxic substance and sequester it from the rest of the organism. The work has important implications for understanding how human cancer cells develop resistance to natural, product-based chemotherapies. Furthermore, the microbiome may play a role in drug resistance. The study was published in the journal Cell Chemical Biology.

“Thanks to this discovery, we now know something about the mechanisms of resistance that’s never been known before for the enediyne antitumor antibiotics,” said study senior author Ben Shen, professor and co-chair of the Scripps Research Institute Department of Chemistry. “This mechanism could be clinically relevant for patients getting these drugs, so it’s very important to study it further.”

Natural products—chemical compounds produced by living organisms—are considered one of the best sources of new drugs and drug leads. “They possess enormous structural and chemical diversity compared with molecules that are made in the lab,” Shen said. Natural products may come from flowers, trees or marine organisms such as sponges. One of the most common sources, however, is soil-dwelling bacteria.

Shen’s lab is focused on a class of natural products called enediynes. These compounds come from bacteria called actinomycetes, which are naturally found in the soil. Two enediyne products are already FDA approved as cancer drugs and are in wide use. But patients who take them often develop resistance. After a period of months or years, tumors can stop responding to the chemotherapy and begin growing again.

While how patients develop resistance to these drugs remains largely unknown, scientists have uncovered two mechanisms that bacteria use to protect themselves from enediynes. “Mechanisms of self-resistance in antibiotic producers serve as outstanding models to predict and combat future drug resistance in a clinical setting,” said Shen.

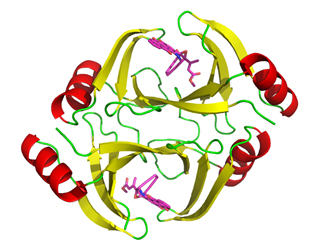

The new study is supported by x-ray diffraction data collected at the 19-ID-D beamline of the Structural Biology Center at the Argonne National Laboratory APS by the researchers from The Scripps Research Institute, Argonne, The University of Chicago, and Rice University. It reports a third, previously undiscovered resistance mechanism that involves three genes called tnmS1, tnmS2 and tnmS3, which encode proteins that allow bacteria to resist the effects of a type of enediynes called tiancimycins. Shen’s lab is currently studying tiancimycins, which hold great promise for new cancer drugs. The proteins work by binding to tiancimycins and keeping them separate from the rest of the organism. (The APS is an Office of Science user facility at Argonne.)

After discovering these genes in actinomycetes and how they work, the investigators studied how widespread these genes are in other microorganisms. They were surprised to find that in addition to actinomycetes, the genes were also present in several microorganisms commonly found in the human microbiota, the collection of microorganisms that naturally inhabit the human body.

“This raises a lot of questions that no one has ever asked before,” Shen said. “I can rationalize why the producing organism would have these genes, because it needs to protect itself from its own metabolites. But why do other microorganisms need these resistance genes?” He notes that it may be possible for gut microbes to pass the products of these genes on to their host—humans—which could contribute to drug resistance.

“These findings raise the possibility that the human microbiota might impact the efficacy of enediyne-based drugs and should be taken into consideration when developing new chemotherapies,” Shen said. “Future efforts to survey the human microbiome for resistance elements should be an important part of natural product-based drug discovery programs.”

See: Chin-Yuan Chang1, Xiaohui Yan1, Ivana Crnovcic1, Thibault Annaval1, Changsoo Chang2, Boguslaw Nocek2, Jeffrey D. Rudolf1, Dong Yang1, Hindra1, Gyorgy Babnigg2, Andrzej Joachimiak2, George N. Phillips, Jr.4, and Ben Shen1*, “Resistance to Enediyne Antitumor by Sequestration,” Cell Chem. Biol. 25, 1 (August 16, 2018). DOI: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.05.012

Author affiliations: 1The Scripps Research Institute, 2Argonne National Laboratory, 3The University of Chicago, 4Rice University

Correspondence: *shenb@scripps.edu

This work is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants GM098248, GM109456, GM121060 (to G.N.P.), GM094585, GM115586 (to A.J.), CA078747, GM115575, and CA204484 (to B.S.). The use of Structural Biology Center beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357 (to A.J.). C.-Y.C., I.C., and J.D.R. are supported in part by postdoctoral fellowships from the Academia Sinica –The Scripps Research Institute Talent Development Program, the German Research Foundation, and the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation, respectively. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.