The original Carnegie Science press release can be read here.

Water makes up more than 70% of our planet and up to 60% of our bodies. Water is so common that we take it for granted. Yet water also has very strange properties compared to most other liquids. Its solid form is less dense than its liquid form, which is why ice floats; its peculiar heat capacity profile has a profound impact on ocean currents and climate; and it can remain liquid at extremely cold temperatures. In addition to ordinary water and water vapor, or steam, there are at least 17 forms of water ice, and two proposed forms of super-cooled liquid water. New work from Carnegie Institution of Washington geophysicists utilizing high-pressure science at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) found evidence of the long-theorized, difficult-to-see low-density liquid phase of water. Their work was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

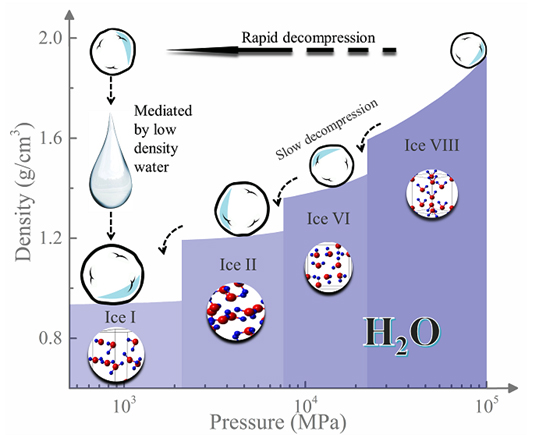

The normal density of water is 1 gram of water molecules per each cubic centimeter. Studies of anomalies in water’s behavior have indicated the existence of liquid water with both lower and higher densities than this standard. But observing these phenomena experimentally has been difficult.

Each molecule has what is called a phase diagram—a sort of chart indicating how its bulk molecular structure changes form under different temperature and pressure conditions. The parts of the phase diagram where low-density water is thought to occur are notoriously difficult to explore, the so-called “water’s no-man’s land,” because they require a path through a series of very specific, very difficult conditions.

But the Carnegie team was able to observe low-density water as an intermediate phase using a newly developed rapid-decompression technique to turn the high-pressure crystalline phase ice-VIII to the diamond-like ice, Ic, at temperatures between about -207 and -163° Fahrenheit (140 and 165 kelvin).

Thanks to the high-brightness x-ray beams provided by the Argonne National Laboratory APS, sophisticated x-ray analysis with angle-dispersive x-ray diffraction experiments at the High Pressure Collaborative Access Team beamline 16-ID-B at the APS confirmed the observation of the low-density liquid water phase, which only lasted for about half a second at -172° Fahrenheit (160 kelvin). (The APS is an Office of Science user facility.)

When ice-VIII was decompressed at moderate speeds, it formed other phases of ice, indicating that the speed of decompression is key to observing the low-density liquid water phase.

“Our newly developed, very fast decompression method was the key to this exciting observation of low-density liquid water as an intermediate between two crystalline phases,” Shen explained.

See: Chuanlong Lin, Jesse S. Smith, Stanislav V. Sinogeikin, and Guoyin Shen, “Experimental evidence of low-density liquid water upon rapid decompression,” Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2018; published ahead of print February 12, 2018. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1716310115

Author affiliation: Carnegie Institution of Washington

Correspondence: *gshen@ciw.edu

This research was supported by the Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science-Basic Energy Science Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering under Award DE-FG02-99ER45775. High Pressure Collaborative Access Team operations are supported by DOE, National Nuclear Security Administration under Award DE-NA0001974. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.