The original Yale University press release by Bill Hathaway can be read here.

The mating display of the male bird of paradise owes its optical extravagance to a background so black it is the envy of telescope and solar panel engineers, according to a new study published in the journal Nature Communications. Their velvety black plumage is so dark it gives the illusion that adjacent patterns of color glow brilliantly, an effect much appreciated by mate-hunting females. Optical measurements showed that these feather patches absorb up to 99.95% of directly incident light, a number comparable to manmade ultra-black materials. The microscopic structures of the wing feathers even resemble those designed by engineers to create ultra-black materials used to facilitate light absorption in solar panels. Researchers utilized various experimental tools, including the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Laboratory, to delve into the structural absorption properties of the feathers, which may find non-avian applications in new or improved biomimetic materials.

“Evolution sometimes ends up with the same solutions as humans,” said senior author Rick Prum, William Robertson Coe Professor of Ornithology of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Yale.

“The juxtaposition of darkest black and colors create to bird and human eye what is essentially an evolved optical illusion,” said lead author Dakota “Cody” McCoy, a Yale graduate now with the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard.

“An apple looks red to us whether it is sitting in the bright sunlight or in the shade because all vertebrate eyes and brains have special wiring to adjust their perception of the world according to ambient light,” McCoy said. “Birds of Paradise, with their super black plumage, increase brilliance of adjacent colors to our eyes, just as we perceive an apple as red even when it is in the shade.”

Intriguingly, the microstructures in the feathers of the bird of paradise not involved in display lack characteristics of ultra-black plumage, another testimony to the importance of sexual selection in evolution.

“Sexual selection has produced some of the most remarkable traits in nature,” Prum said. “Hopefully, engineers can use what the Bird of Paradise teaches us to improve our own human technologies as well.”

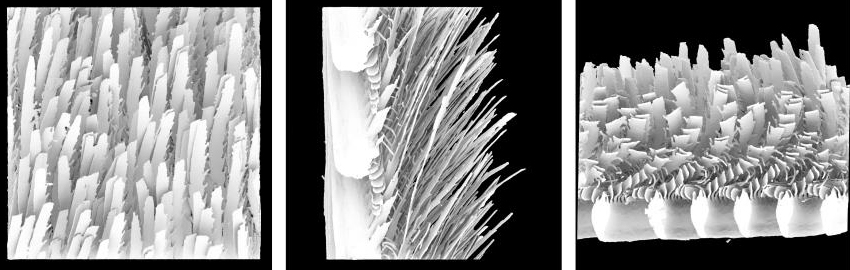

The work by researchers from Harvard University, the Smithsonian Institution, and Yale University utilized scanning electron microscopy and ray-tracing simulations, as well as synchrotron x-ray nano-computed tomography at the X-ray Science Division 2-BM-A,B x-ray beamline at the APS to reveal the microscopic structures of the super black feathers (Fig. 1). The APS is an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory.

Whereas other birds’ feathers have lots of tiny filaments that lie flat and are neatly organized, on the birds of paradise these filaments are tightly packed and bend upward, with deep cavities between them. As light enters the feather, it bounces around these cavities and gradually gets absorbed. X-ray tomography helps to reveal the barbule network structure (“cavities” above). They performed ray-tracing simulation and conclude such specific barbule structure causes extreme light absorption.

See: Dakota E. McCoy 1, Teresa Feo2, Todd Alan Harvey3, and Richard O. Prum3, “Structural absorption by barbule microstructures of super black bird of paradise feathers,” Nat Commun. 9, published online 09 January 2018. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-02088-w

Author affiliations: 1Harvard University, 2Smithsonian Institution, 3Yale University

Correspondence: *dakotamccoy@g.harvard.edu

This research was funded by the W. R. Coe Fund of Yale University, by a Sigma XI student research fellowship to D.E.M., and by a Mind, Brain, and Behavior Graduate Student Award to D.E.M. D.E.M. was supported by the Department of Defense (DoD) through the National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship Program. D.E.M. was also supported by a Theodore H. Ashford Graduate Fellowship in the Sciences. T.J.F. was supported by a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship in Biology (#1523857). Xianghui Xiao and the 2-BM beamline group provided assistance with CT scanning and analysis at the APS facility. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.