Understanding what our Earth is made of is crucial to understanding our globe, how seismic waves travel through it, and the life cycle of any given mineral. But exploring what lies under the Earth's crust isn't simple – indeed, it can be just as difficult as determining what makes up other planets. Short of burrowing down some 1,800 miles into the Earth, scientists must rely on work in the lab to understand the behavior of minerals at the intense heat and pressures experienced in such inaccessible regions.

Recent work at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) shows that a mineral known as perovskite, which had been thought to be the dominant mineral in the entire lower mantle – stretching from around 400 to 1,800 miles down – is unstable at the lowest depths. When studied under high temperatures and high pressures in the lab to simulate conditions at the deep lower mantle, the perovskite separated into two distinct atomic structures (known as phases). Including new minerals in our understanding of the Earth could lead to a serious readjustment of current theories.

"The lower mantle may contain major amounts of previously unidentified phases of perovskite,” said Li Zhang, of the Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research in Shanghai, China, and first author on the Science article about this work. “All Earth models need to be reconsidered to take this into account."

Indeed, such geodynamic models have already been changed quite a bit in the last 10 years. The prevailing theory in the 20th century was that perovskite dominated the lower mantle. The perovskite was not thought to change structure until the bottommost part of the mantle, where the pressures help it transition into an iron-poor mineral called postperovskite.

However, data showing how seismic waves move through the Earth at about 1,200 miles deep doesn't perfectly jibe with this theory. The waves travel in puzzling ways that simply can't be explained if they're traveling through perovskite and post-perovskite.

For the current research, performed by scientists from the Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research (China), the Carnegie Institution of Washington, Stanford University, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, the University of Minnesota, and Argonne National Laboratory, the team simulated deep lower mantle conditions to tease out just what was happening in this region.

The researchers squeezed pervoskite between diamond anvil cells to bring the samples to the appropriate pressure. Simultaneously, the samples were heated with lasers to between 3,500 and 3,800 degrees Fahrenheit.

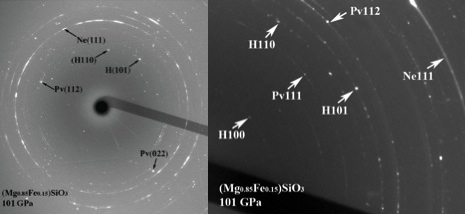

The team then determined the atomic structure of the samples via synchrotron x-ray diffraction using the High Pressure Collaborative Access Team 16-ID-B beamline, the GeoSoilEnviroCARS 13-ID-D beamline, and the Argonne X-ray Science Division 34-ID-E beamline, all at the Argonne APS, which is an Office of Science user facility.

The scientists found that the pervoskite had undergone an unexpected change. "Surprisingly, we found that the perovskite was unstable," said Zhang. "It split into two phases, one without iron and one that was iron-rich, with a hexagonal structure, called the H-phase [see the figure]."

This H-phase may well help explain the enigmatic ways that seismic waves travel through the deep lower mantle.

Zhang says that the team will next try to tease out more detail about the mineral's structure and determine if it jibes with seismic observation. — Karen Fox

See: Li Zhang1,2*, Yue Meng2, Wenge Yang1,2, LinWang1,2, Wendy L. Mao3,4, Qiao-Shi Zeng3, Jong Seok Jeong5, Andrew J. Wagner5, K. Andre Mkhoyan5, Wenjun Liu6, Ruqing Xu6, Ho-kwang Mao1,2, “Disproportionation of (Mg,Fe)SiO3 perovskite in Earth’s deep lower mantle,” Science 344(6186), 877 (23 May 2014). DOI: 10.1126/science.1250274

Author affiliations: 1Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research, 2Carnegie Institution of Washington, 3Stanford University, 4SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, 5University of Minnesota, 6Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: * zhangli@hpstar.ac.cn

The research is supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) grants EAR-0911492, EAR-1119504, EAR-1141929, and EAR-1345112. High Pressure Collaborative Access Team operations are supported by the U.S. Department of Energy–National Nuclear Security Administration (DOE-NNSA) under award DE-NA0001974 and DOE–Basic Energy Sciences (BES) under award DE-FG02-99ER45775, with partial instrumentation funding by the NSF. GeoSoilEnviroCARS is supported by NSF-Earth Sciences (EAR 1128799) and DOE-GeoSciences (DE-FG02-94ER14466).This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.