The original University of California, Merced news item by Lorena Anderson can be read here.

A new paper released in the prestigious journal Science explains how the labs of UC Merced professor Andy LiWang and his colleagues, professor Carrie Partch at UC Santa Cruz and professor Susan Golden at UC San Diego, imaged the proteins in large complexes that direct cyanobacterial circadian rhythms, or biological clocks and made spectroscopic “snapshots” of their different formations using x-ray crystallography at two U.S. Department of Energy x-ray light sources and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

Circadian clocks are an ancient evolutionary adaptation that synchronizes genetic, epigenetic and metabolic activities with the Earth’s rotation. Humans instinctively wake when it’s morning and sleep when it’s evening — dictated by our circadian clocks.

How that inner clock works is still being discovered.

“Imagine if you wanted to see how a mechanical Swiss watch works, but all you had were the individual gears and springs and no instructions about how they went together,” LiWang said. “You wouldn’t know how the watch runs. You have to see all the parts interacting.”

The researchers use cyanobacteria, which are are among Earth’s oldest living creatures. Through photosynthesis and oxygen production, these bacteria are likely the reason all other aerobic organisms exist. Their circadian clock orchestrates gene expression for the majority of the genome to regulate daytime and nighttime metabolic processes that enhance fitness and acutely affect their survival.

Cyanobacteria make a perfect subject for structural studies because their circadian clocks can be isolated and studied in test tubes outside their living cells. The research is funded by the National Institutes of Health, and LiWang also receives funding from the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research to build on the circadian clock research he has conducted for several years, in hopes of being able to better explain human circadian rhythms.

The researchers set out to capture the structures of the bacteria’s protein clockwork — the equivalent of looking at a watch with all its parts assembled.

“The biggest mystery was what the clock was doing at night,” LiWang said.

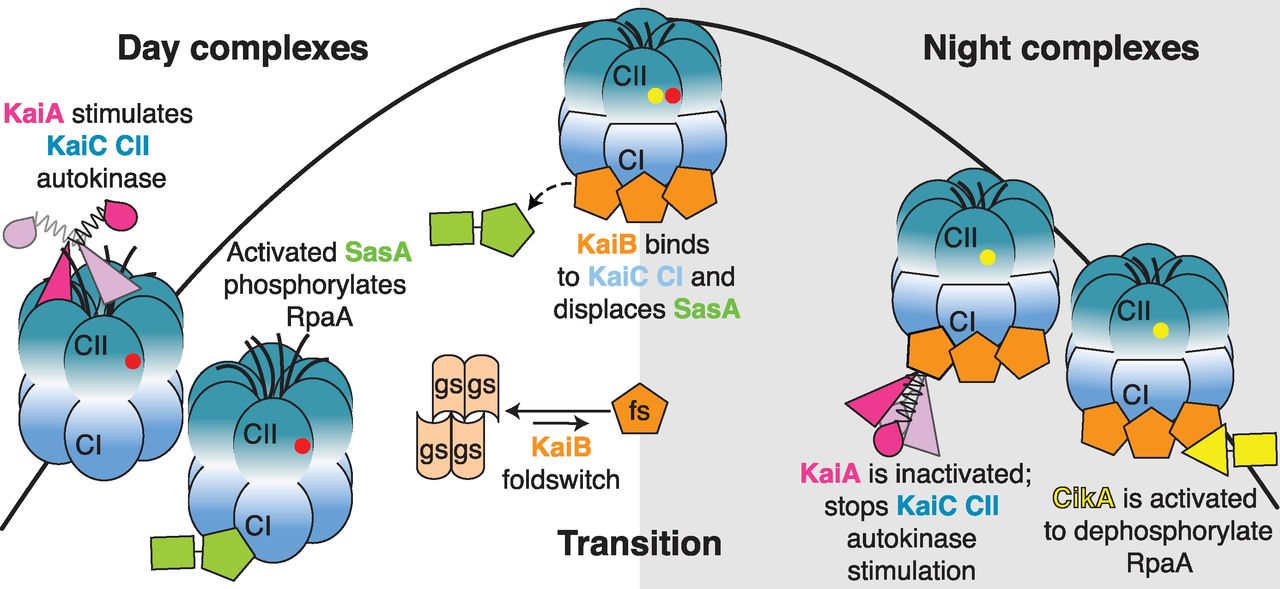

LiWang, Partch, and Golden and their labs have been working to understand how three proteins that drive the bacteria’s circadian clock — KaiA, KaiB and KaiC — arrange themselves at different times of the day and how they transition to night.

LiWang mutated KaiB so it could form stable clock protein assemblies.

Partch, an expert in both cyanobacterial and mammalian clocks, carried out the crystallography. Golden, a pioneer of cyanobacterial biology, performed genetic and cellular experiments in live cyanobacteria.

A tricky part of being able to visualize the structures is that the protein assemblies needed to be stable enough to form crystals so the researchers could shoot x-rays through them to produce crisp diffraction patterns, utilizing two Office of Science user facilities, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and National Cancer Institute (GM/CA-XSD) 23-ID-B beamline at the Argonne National Laboratory Advanced Photon Source and the 8.3.1 beamline at the Advanced Light Source at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

KaiB, though, flips between two different shapes, and is only active when it’s in an unstable shape — a situation that until now made crystallization impossible.

“We mutated KaiB so that it stayed in its active shape, and when we added KaiA and KaiC they arranged themselves around it as they do at night,” LiWang said. “We found the secret sauce that allows us to figure out how the springs and gears go together.”

They were amazed that they obtained crystals within a day of combining the proteins. They also solved an NMR structure of a complex between the active form of KaiB and the domain of a protein (CikA) that transmits signals to regulate gene expression in cyanobacteria.

“It’s really remarkable that the cyanobacterial clock is so dependent on this rare state of KaiB,” Partch said. “The mechanistic information we’re getting out of these structures is allowing us to piece together how the clock manages to keep 24-hour time. We’re now looking for similar clues in other circadian timekeeping systems, including our own.”

The next big step for this team will be to see if they can peer closely at the fully functional, biological Swiss watch as its molecular components move.

LiWang, Partch and Golden are members of the Center for Circadian Biology at UC San Diego, which provides a networking hub for these three labs to interact closely and to meet with other circadian biologists in the region.

“The structures of these complexes show the elegance of the cyanobacterial circadian clock,” Golden said, “in which the timekeeping gears mesh neatly with the time-telling ‘hands’ of the clock.

“From these structures, we can understand not only how the mechanism ticks, but also how the information gets out to control the rhythmic turning on and off of genes in the cell.”

Below are two animations created at the BioClock Studio at UC San Diego that help illustrate the proteins' movements and arrangements.

This animation demonstrates the circadian oscillator mechanism in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus. It was produced and developed by members of the BioClock Studio Winter 2016 at UC San Diego. Credit: The BioClock Studio at UC San Diego

This animation shows how the core circadian oscillator in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus sends output to regulate the timing of other intracellular processes. It was produced and developed by members of the BioClock Studio Winter 2016 at UC San Diego.

Credit: The BioClock Studio at UC San Diego

See: Roger Tseng, Nicolette F. Goularte, Archana Chavan, Jansen Luu, Susan E. Cohen, Yong-Gang Chang, Joel Heisler, Sheng Li, Alicia K. Michael, Sarvind Tripathi, Susan S. Golden, Andy LiWang*, and Carrie L. Partch**, “Structural basis of the day-night transition in a bacterial circadian clock,” Science 355, 1174 (17 March 2017). DOI: 10.1126/science.aag2516

Correspondence: *aliwang@ucmerced.edu, **cpartch@ucsc.edu

Access to the 8.3.1 beamline was provided by the University of California Office of the President Multicampus Research Programs and Initiatives grant MR-15-328599 and the Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research, which is partly funded by the Sandler Foundation. The Advanced Light Source (contract DE-AC02-05CH11231) is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy. This work was supported by grants from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-13-1-0154 to A.L.), U.S. National Institutes of Health (R01GM107521 to A.L., R01GM107069 to C.L.P., F31CA189660 to A.K.M., and R35GM118290 to S.S.G.). R.T. was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, and S.E.C. was supported by the American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship PF-12-262-01-MPC. S.L. and the Biomolecular/Proteomics Mass Spectrometry Facility are supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (1U19AI117905, R01GM020501, and R01AI101436). GM/CA-XSD has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM-12006). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.