Like humans, insects are aerobic organisms — they use oxygen to drive the reactions that produce the energy needed for life. But insects don’t have lungs and their blood doesn’t carry much oxygen, so how do they take in and transport the oxygen their cells need? Insects have a separate respiratory system that allows passive diffusion of gas into and out of their bodies through holes, called “spiracles,” in their exoskeletons.

Diffusion is sufficient for the needs of small or low-activity insects but larger or more active insects have developed another method, termed abdominal pumping, that uses body movements to generate gas-moving pressure changes in the body. Interestingly, abdominal pumping has also been observed in developing insects that generally have lower metabolic needs. To understand more about the role of abdominal pumping in developing insects, researchers from Virginia Tech used x-ray phase contrast imaging at X-ray Science Division beamline 32-ID-B,C at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) to view the tracheal system of the pupal form of the darkling beetle, Zophobas morio. Their results provide insights into how insects produce flows at very small scales that could lead to innovations in bio-inspired microfluidic engineering.

Insect respiration has been studied in small and large insects and a direct correlation has been made between increased energy needs and abdominal pumping. In general, insects have been reported to do more abdominal pumping if they are larger and if they engage in activities such as flying or if they are under stress. Pupal forms of developing insects, because they are immobile and have lower energy needs, require less oxygen, and should not need to use ventilation. Yet, they employ abdominal pumping. It’s just not clear why they the make the effort.

In order to understand this observation, the researchers sought to design a system that would allow them to monitor circulatory system pressure changes, airflow, and abdominal and tracheal movements, all at the same time in a living beetle pupa.

In order to achieve this, they mounted pupae of the Zophobas beetle (first figure) onto a small platform and inserted a hydrostatic pressure sensor into the body of the pupa. This let them assess pressure changes in the circulatory system that are associated with airflow.

To measure airflow, they built a customized respirometry chamber to monitor carbon dioxide coming out of the spiracles. These carbon dioxide bursts can be correlated with pressure changes to identify airflow events.

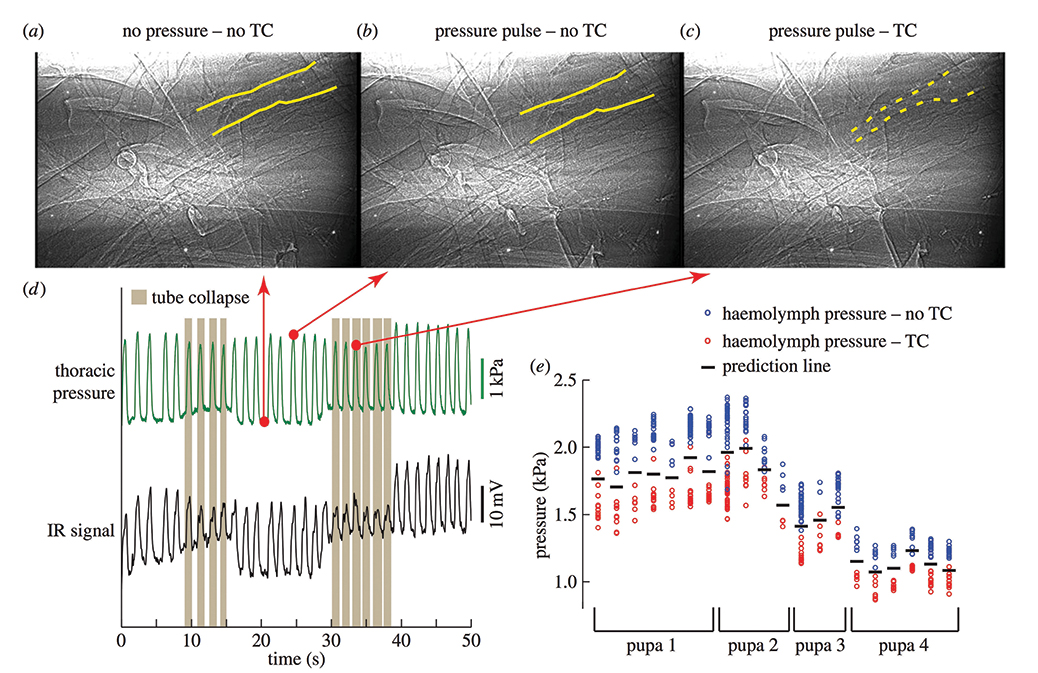

To image abdominal movements, they used infrared sensors or a video camera on the outside of the animal; tracheal movements inside the animal were monitored using x-ray phase contrast imaging at the Argonne APS beamline.

With these tools, the team was able to monitor carbon dioxide bursts to determine whether spiracles were open (carbon dioxide burst) or closed (no burst), and whether these respiratory activities correlated with compression (air movement) or relaxation of the trachea. Finally, these respiratory activities were correlated to abdominal pumping events.

The team’s hypothesis was that when there was no carbon dioxide burst, and spiracles were closed, the magnitude of abdominal pumping would be low and the trachea would not collapse. If the spiracles were open, abdominal pumping would produce active ventilation by increasing the pressure in the circulatory system and leading to tracheal collapse and air exchange.

However, what they observed was somewhat different.

Active ventilation events, those with a carbon dioxide burst correlated to a tracheal collapse and circulatory pressure increase, were always associated with an abdominal pump. But 63.7% of abdominal pumps occurred without an associated tracheal collapse and actually showed higher pressures.

There are two interesting findings here.

First, the team was able to conclusively demonstrate that pupae do indeed use abdominal pumping to facilitate active respiration. All of the active airflow events they observed were associated with an abdominal pump. This finding was facilitated by the set-up at the APS, which allowed them to visualize for the first time the associated tracheal collapse in a pupa.

Second, this work strongly suggests that pupae also perform abdominal pumping for other reasons. Over half of the abdominal pumps occurred when the spiracles were closed and did not result in respiration.

The team hypothesizes that other roles for abdominal pumping may include internal gas mixing, support of blood circulation, or management of water loss; answering this question will be the focus of future work.

— Sandy Field

See: Hodjat Pendar, Melissa Kenny, and John J. Socha, “Tracheal compression in pupae of the beetle Zophobas morio,” Bio. Lett. 11(6), 20150259 (17 June 2015). DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0259

Author affiliation: Virginia Tech

Correspondence: * hpendar@vt.edu

Videos by the researchers related to this study can be viewed here.

This Biology Letters article was the subject of a the June 22, 2015, Science magazine SCIENCESHOT, “Video: Young beetles pump their abs to breathe” by Juan David Romero, DOI: 10.1126/science.aac6881, and was the cover article for Biology Letters Vol. 11, Issue 6, June 2015.

This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.