The original UC Berkeley press release by Robert Sanders.

Carbon monoxide (CO) is an insidious poison because it loves the iron in our blood; it pushes oxygen out of iron-based hemoglobin, leading to painful asphyxiation. This affinity for iron comes in handy in a newly created material that can absorb carbon monoxide far better than other materials, with potential applications in industrial processes like syngas production, where CO is a key player, and reactions where CO is an unwanted contaminant. A number of characterization and measurement techniques contributed to this groundbreaking research, including critical experiments at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS). The results of these studies were published online ahead of print in the journal Nature.

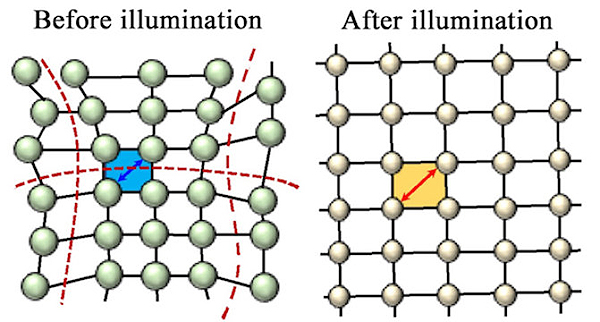

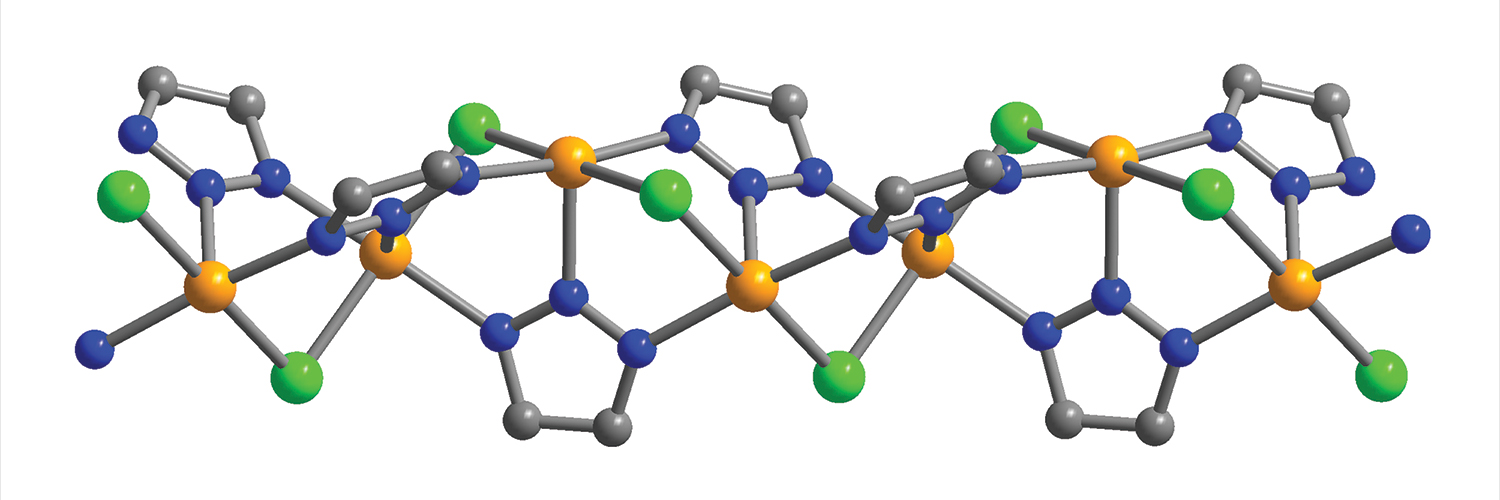

The new material is a metal-organic framework – an amazingly porous material with a growing list of applications – that incorporates chains of iron atoms tuned to attract CO and exclude other chemical compounds. When CO binds to an iron atom in the MOF, it changes the environment of neighboring iron atoms to make them even more attractive to CO, creating a chain reaction.

“We see this cooperative adsorption effect where binding at one site activates the neighboring sites, which means that all of a sudden you go from very little adsorption to essentially saturating the material with CO,” said senior researcher Jeffrey Long, a UC Berkeley professor of chemistry and faculty scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and corresponding author of the Nature article. The research team included members from the University of Texas at Austin, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and the University of Turin (Italy).

The CO binding flips the spin state of iron, hence Long’s terminology for the material: “spin-transition MOFs.”

Two years ago, Long accidentally stumbled across the first of this type of cooperative adsorbent when he created a MOF that adsorbed carbon dioxide far better than other materials.

“The carbon dioxide capture material we lucked into in 2015 was a first-of-its-kind material for cooperative adsorption,” he said. “Now we’ve shown that cooperative MOF adsorbents can be built by design to target other key industrially relevant molecules for separation. It is a fundamental new mechanism where, by adjusting the ligands bound to the iron, you might be able to get unsaturated hydrocarbons like acetylene, ethylene and propylene to bind also.” High-resolution synchrotron x-ray powder diffraction data for two different MOFs, and versions of those MOFs dosed with CO, were collected at X-ray Science Division (XSD) beamline 11-BM-B and XSD beamline 17-BM-B, both at the APS, which is an Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory. These studies revealed important information about the structures of the new materials, and about the method by which the MOFs absorbed CO.

CO is used in a variety of industrial processes, including as a component of synthesis gas – a mix of CO and hydrogen used to make synthetic fuel or to synthesize other chemicals. These MOFs might serve as reservoirs for CO to maintain the correct ratio of CO to hydrogen for a particular reaction.

CO is also an essential intermediate in iron and steel production. Long predicts that the new MOF could be used to extract CO from the mixed-gas byproducts of such manufacturing to provide recycled CO for reuse in the chemical industry. In most cases today, these mixed gases are burned, Long said, accounting for a large portion of the greenhouse gases produced by the steel industry.

Such MOFs also could help suck up CO in reactions where CO poisons the catalyst, such as in the production of ammonia for fertilizers or polymers like polyethylene and polypropylene, and in hydrogen fuel cells.

“There are lots of places where you want to separate CO sufficiently in industry, and these spin transition MOFs can potentially have a role there,” Long said.

In practice, the MOFs would adsorb CO at room temperature, and then be heated slightly to drive off the CO, readying the MOF for reuse. These spin-transition MOFs can be precisely tuned so that only a small rise in temperature – from 20 C to 60 C, for example — releases the CO, requiring significantly less energy than other capture or storage technologies, such as cryogenic distillation.

As an example, they compared their spin-transition MOF to a commercial, liquid absorbent process for recovering CO, which is called COSORB. Initial calculations showed that the MOF requires just 32 percent of the energy to capture and reuse CO as the COSORB process.

See: Douglas A. Reed1, Benjamin K. Keitz1,2, Julia Oktawiec1, Jarad A. Mason1, Tomom Runčevski1,3, Dianne J. Xiao1, Lucy E. Darago1, Valentina Crocella4, Silvia Bordiga4, and Jeffrey R. Long1,3*, “A spin transition mechanism for cooperative adsorption in metal–organic frameworks,” Nature, published online 11 September 2017. DOI: 10.1038/nature23674

Author affiliations: 1University of California, Berkeley, 2University of Texas at Austin, 3Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 4University of Turin

Correspondence: *jrlong@berkeley.edu

This research was supported through the Center for Gas Separations Relevant to Clean Energy Technologies, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences under award DE-SC0001015. D.A.R., J.O., J.A.M., D.J.X. and L.E.D. thank the National Science Foundation for graduate fellowship support. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02- 06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.