The original Arizona State University press release by Joe Caspermeyer can be read here.

Every day, enough sunlight hits the Earth to power the planet many times over — if only we could more efficiently capture all the energy. So scientists have looked at nature for inspiration to do it better. By solving the heart of photosynthesis in a sun-loving, soil-dwelling bacterium, a team of scientists working at two U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) national research facilities has gained the most fundamental understanding of the inner workings of photosynthesis, and how this vital process differs between plants' systems. Their discovery, published in the journal Science, may provide a brand-new template for laying the groundwork for organic-based solar panel design, known as “artificial leaves,” for solar energy, or possible renewable biofuel applications.

With today’s solar panels limited by their efficiency (currently, more than 80% of available solar energy is lost as heat), scientists have been trying to better understand the way photosynthetic plants and bacteria capture sunlight.

“Nature’s invention of photosynthesis is the single most important energy conversion process driving the biosphere, and photosynthesis forever changed the Earth’s atmosphere,” said Raimund Fromme, associate research professor at the Arizona State University (ASU) Biodesign Institute’s Center for Applied Structural Biology and in the School of Molecular Sciences.

More than 3 billion years ago, our planet had an atmosphere without oxygen. At this time, nature figured out a way to capture the sunlight and convert it to food to take advantage of this everlasting energy source.

Life’s solar panels, which scientists call photosystems, are used by plants, algae and photosynthetic bacteria as an incredibly efficient system for capturing almost every available photon of light to grow and thrive, filling every nook and cranny on Earth.

“To truly and fully understand photosynthesis, one has to follow the process of converting light into chemical energy,” said Fromme. “This is one of the fastest chemical reactions ever studied, which is part of what makes it so hard to study and understand.”

The timescales of photosynthesis turn a bolt of lightning into a snail-like pace by comparison. Photosynthesis reactions occur at the scale of picoseconds, which is one-trillionth of a second. A picosecond is to one second as one second is to 37,000 years.

But the ASU structural biologists are using ever more powerful x-ray technology to one day catch up to the light by capturing freeze-frame images of crystallized proteins throughout the whole process.

In an effort to study photosynthesis, Fromme explored photosynthesis in its simplest form, in heliobacteria, which were first found in muddy soils near hot springs in far-flung locales like Iceland. The single-celled heliobacteria are simpler, yet fundamentally different than plants. For instance, during photosynthesis, instead of using water like plants, heliobacteria use hydrogen sulfide. They grow without oxygen, and after photosynthesis, give off a rotten-egg-smelling sulfur gas in place of oxygen.

Heliobacteria have used their unique place to successfully carve out their own ecological niche because they use a near-infrared wavelength of light for photosynthesis, which is perfect for low-light conditions found in places like Iceland or murky, muddy rice paddies. Plants simply can’t compete.

Scientists have wanted to understand how heliobacteria accomplish this.

At the heart of photosynthesis is a reaction center (RC); it’s an elaborate complex of pigments and proteins that turn light into electrons to power the cell.

The heliobacteria RC has been proposed to be the closest thing alive to the earliest common ancestor of all photosynthetic reaction centers, when, around 3 billion years ago, the early Earth contained sulfur rich seas and little oxygen. But successfully purifying an RC protein and growing crystals needed for x-ray experiments can be a lengthy, difficult process.

In particular, Fromme’s research project was started seven years ago as postdoctoral researcher Iosifina Sarrou first improved the preparation of the heliobacterial reaction center. After many initial trials of crystallization, an x-ray diffracting crystal charge was found.

“This is the moment a crystallographer is waiting for,” said Fromme, explaining the years it can take to grow the perfect protein crystal suitable for x-ray studies.

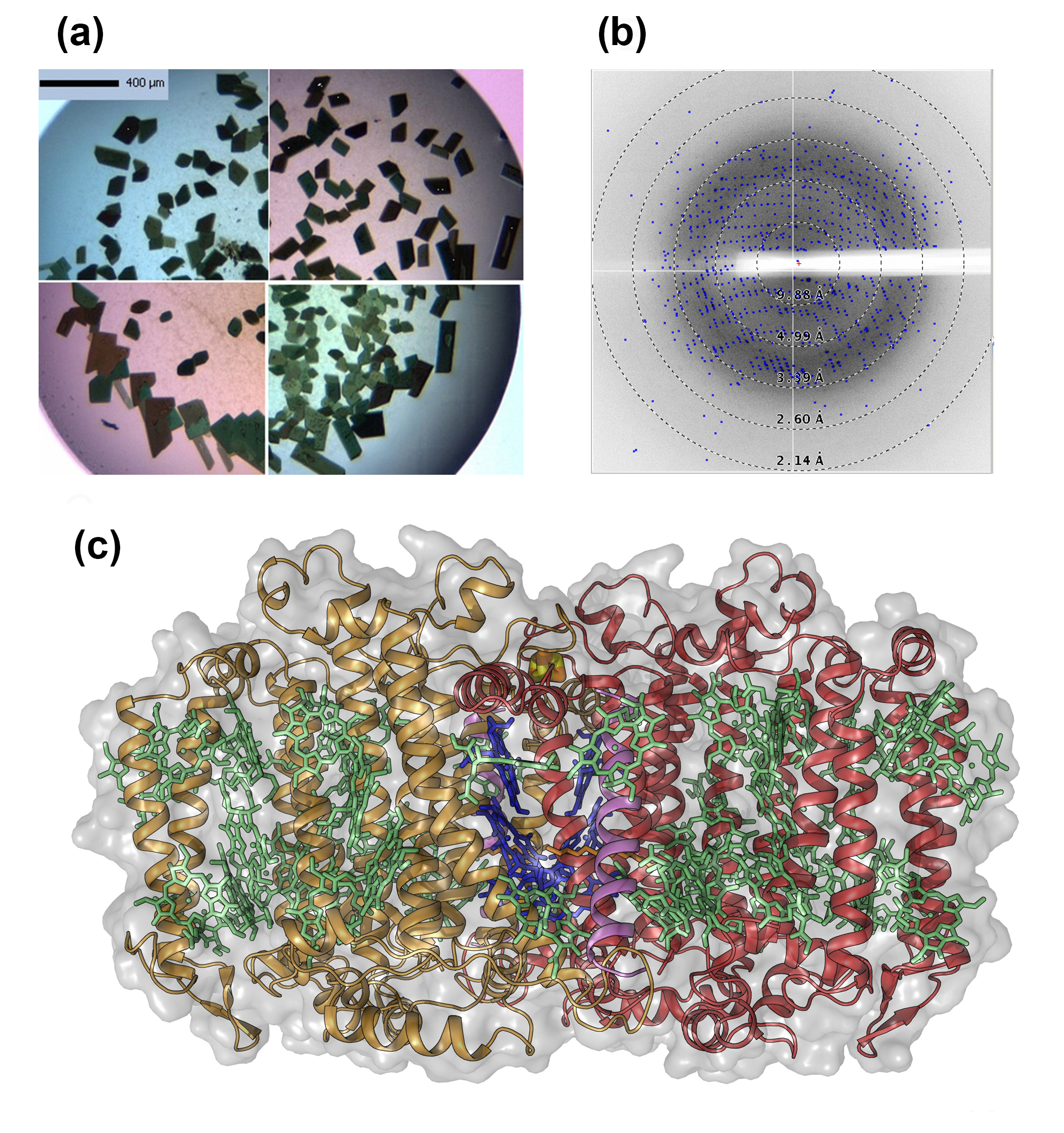

It can take years to grow the perfect protein crystal suitable for x-ray studies. On the left are emerald-colored protein crystals. The figure on the right is the diffraction pattern after the crystals were exposed to x-rays. Scientists can build the 3-D structure of a protein from these patterns.

Shortly after these encouraging results, Christopher Gisriel joined the team and improved the diffraction quality to see the atomic details. Still, the research team could not solve a crystallographic structure.

This hiatus took two years, until August 2016. Then, finally, a breakthrough came.

At this point “a thrilling discovery on unchartered territory began, as each new chlorophyll was cheered,” Fromme remembered, and “proved everyone’s initial prediction on the heliobacteria’s RC was wrong.”

Using x-ray light from two DOE Office of Science user facilities, the Structural Biology Center (SBC-CAT) 19-ID-D beamline at the Argonne National Laboratory Advanced Photon Source; and beamline 8.2.1 at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Advanced Light Source, Fromme’s ASU group and colleagues from DESY (Germany) and The Pennsylvania State University visualized the heliobacteria RCs for the first time at near-atomic, 2.2-angstrom resolution.

They found an almost perfect symmetry in the heliobacter RC, which helps it gather every available photon of near infrared light.

Furthermore, with the explosion of DNA-sequencing technology, and with the potential ability to understand all of the genes and proteins across life, they also traced the evolution of the photosynthesis RCs. They wanted to know: Could this simplest of reaction centers have spawned all others, leading to greater complexity over the eons? In evolutionary terms, this means that the heliobacteria RC may have first come from a single gene.

“This structure preserves characteristics of the ancestral reaction center, providing insights into the evolution of photosynthesis,” explained Fromme’s colleague Kevin Redding, a researcher at ASU’s Center for Bioenergy and Photosynthesis. “From the new structures we have, it would certainly make sense for a compelling case.”

Then, the gene may have been duplicated to increase the evolutionary complexity.

“This likely occurred on at least three separate occasions, leading to the creation of all the different and more complex reactions center found in other photosynthetic bacteria and plants,” said Fromme.

Fromme’s group is excited about the potential of the new results. Such an understanding could one-day help research groups around the world build an artificial photosynthesis center.

See: Christopher Gisriel1, Iosifina Sarrou2, Bryan Ferlez3, John H. Golbeck3, Kevin E. Redding1, and Raimund Fromme1,4*, “Structure of a symmetric photosynthetic reaction center–photosystem,” Science, published on line 27 July 2017. DOI: 10.1126/science.aan5611

Author affiliations: 1Arizona State University, 2Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY), 3The Pennsylvania State University, 4Biodesign Institute (ASU)

Correspondence: *raimund.fromme@asu.edu

This work was funded by the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. DOE through Grant (DE-SC0010575 to K.R., R.F., and J.H.G.) and supported with x-ray crystallographic equipment and infrastructure provided by Petra Fromme of the Biodesign Center for Applied Structural Discovery at Arizona State University. The Berkeley Center for Structural Biology is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. SBC-CAT is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. DOE Office of Science Biological and Environmental Research Program under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02- 06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.