The original Washington University in St. Louis press release by Tamara Bhandari can be read here.

Each year in the United States, more than 57,000 children younger than five years old are hospitalized due to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection, and about 14,000 adults older than 65 die from it. By age two, most children have been infected with RSV, which usually causes only mild cold symptoms. But people with weakened immune systems, such as infants and the elderly, can face serious complications, including pneumonia and – in some cases – death. Now, scientists studying the virus using bright x-rays from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Advanced Photon Source have found clues to how RSV causes disease. They mapped the molecular structure of an RSV protein that interferes with the body’s ability to fight off the virus. Knowing the structure of the protein will help them understand how the virus impedes the immune response, potentially leading to a vaccine or treatment for this common infection.

“We solved the structure of a protein that has eluded the field for quite some time,” said Daisy Leung, an assistant professor of pathology and immunology, and of biochemistry and molecular biophysics at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and the study’s co-senior author. “Now that we have the structure, we’re able to see what the protein looks like, which will help us define what it does and how it does it. And that could lead, down the road, to new targets for vaccine or drug development.”

The study was published in Nature Microbiology.

There is no approved vaccine for RSV and treatment is limited – the antiviral drug ribavirin is used only in the most severe cases because it is expensive and not very effective – so most people with RSV receive supportive care to make them more comfortable while their bodies fight off the virus.

For people with weakened immune systems, though, fighting RSV can be tough because the virus can fight back. Scientists have long known that a non-structural RSV protein is key to the virus’s ability to evade the immune response. However, the structure of that protein, known as NS1, was unknown. Without seeing what the protein looked like, scientists were unable to determine exactly how NS1 interfered with the immune system.

It’s an enigmatic protein. Everybody thinks it does many different things, but we’ve never had a framework to study how and why the protein does what it does,” said co-senior author Gaya Amarasinghe, an associate professor of pathology and immunology.

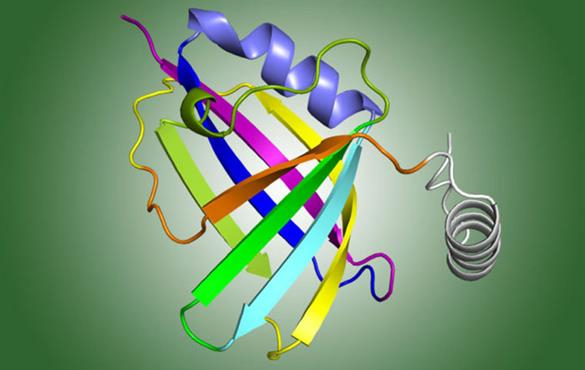

Leung, Amarasinghe, and colleagues used x-ray crystallography at the Structural Biology Center Collaborative Access Team (SBC-CAT) 19-ID-D facility at the APS to determine the 3-D structure of NS1. Then, in a detailed analysis of the structure, they identified a piece of the protein, known as the alpha 3 helix, which might be critical for suppressing the immune response. (The APS is an Office of Science user facility).

To test their hypothesis, the researchers created different versions of the NS1 protein, some with the alpha 3 helix region intact, and some with it mutated. The Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis researchers, in collaboration with colleagues from Georgia State University, ITMO University (Russia), the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, and the Emory University School of Medicine, tested the functional impact of helix 3 and created a set of viruses containing either the original or the mutant NS1 genes, and measured the effect on the immune response when they infected cells with these viruses.

They found that the viruses with the mutated helix region did not suppress the immune response while the ones with the intact helix region did.

“One of the surprising things we found was that this protein does not target just one set of genes related to the immune response, but it globally modulates the immune response,” said Amarasinghe.

The findings show that the alpha 3 helix region is necessary for the virus to dial the body’s immune response down. By suppressing the immune response, the virus gives itself a better chance of surviving and multiplying, or in other words, of causing disease.

RSV usually can only cause disease in people whose immune systems are already weak, so a vaccine or treatment that targets the alpha 3 helix to prevent immune suppression may be just what people need to be able to successfully fight off the virus.

See: Srirupa Chatterjee1, Priya Luthra2, Ekaterina Esaulova1, Eugene Agapov1, Benjamin C. Yen4, Dominika M. Borek5, Megan R. Edwards1, Anuradha Mittal1, David S. Jordan1, Parameshwar Ramanan1, Martin L. Moore6, Rohit V. Pappu1, Michael J. Holtzman1, Maxim N. Artyomov1, Christopher F. Basler2, Gaya K. Amarasinghe1*, Daisy W. Leung1**, "Structural basis for human respiratory syncytial virus NS1-mediated modulation of host responses," Nat. Microbio. 2, 17101 (2017). DOI: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.101

Author affiliations: 1Washington University School of Medicine, 2Georgia State University, 3ITMO University, 4Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 5University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 6Emory University School of Medicine

Correspondence: *gamarasinghe@wustl.edu , **dwleung@wustl.edu

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant numbers R01AI107056, R01AI123926, R01AI114654, U191099565, U19AI109945, U19AI109664, U19AI070489, R01AI111605, R01AI130591, R01AI087798, U19AI095227, and T32-CA09547-37; the Defense Threat Reduction Agency of the Department of Defense, grant numbers HDTRA1-16-0033 and HDTRA1-16-0033; the National Science Foundation, grant number MCB-1121867; the Children’s Discovery Institute, a partnership between Washington University School of Medicine and St. Louis Children’s Hospital, grant number PD-II-2013-272; and the American Heart Association, 15POST25140009. SBC-CAT is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science Biological and Environmental Research Program under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02- 06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.