The original Michigan State University press release can be read here.

A team of scientists utilizing the extreme brightness of x-rays from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) has pinpointed a new source of nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas that’s more potent than carbon dioxide. The culprit? Tiny bits of decomposing leaves in soil.

This new discovery, featured in Nature Geoscience, could help refine nitrous oxide emission predictions as well as guide future agriculture and soil management practices.

“Most nitrous oxide is produced within teaspoon-sized volumes of soil, and these so-called ‘hot spots’ can emit a lot of nitrous oxide quickly,” said Sasha Kravchenko, Michigan State University (MSU) plant, soil, and microbial scientist and lead author of the study. “But the reason for occurrence of these hot spots has mystified soil microbiologists since it was discovered several decades ago.”

Part of the vexation was due, in part, to scientists looking at larger spatial scales. It’s difficult to study and label an entire field as a source of greenhouse gas emissions when the source is grams of soil harboring decomposing leaves. Changing the view from binoculars to microscopes will help improve N2O emission predictions, which traditionally are about 50% accurate, at best. Nitrous oxide’s global warming potential is 300 times greater than carbon dioxide, and emissions are largely driven by agricultural practices.

“This work sheds new light on what drives emissions of nitrous oxide from productive farmlands,” said John Schade, a program director for the National Science Foundation’s (NSF’s) Long-Term Ecological Research program, which co-funded the research with the NSF’s Earth Sciences Division. “We need studies like this to guide the creation of sustainable agricultural practices necessary to feed a growing human population with minimal environmental impact.”

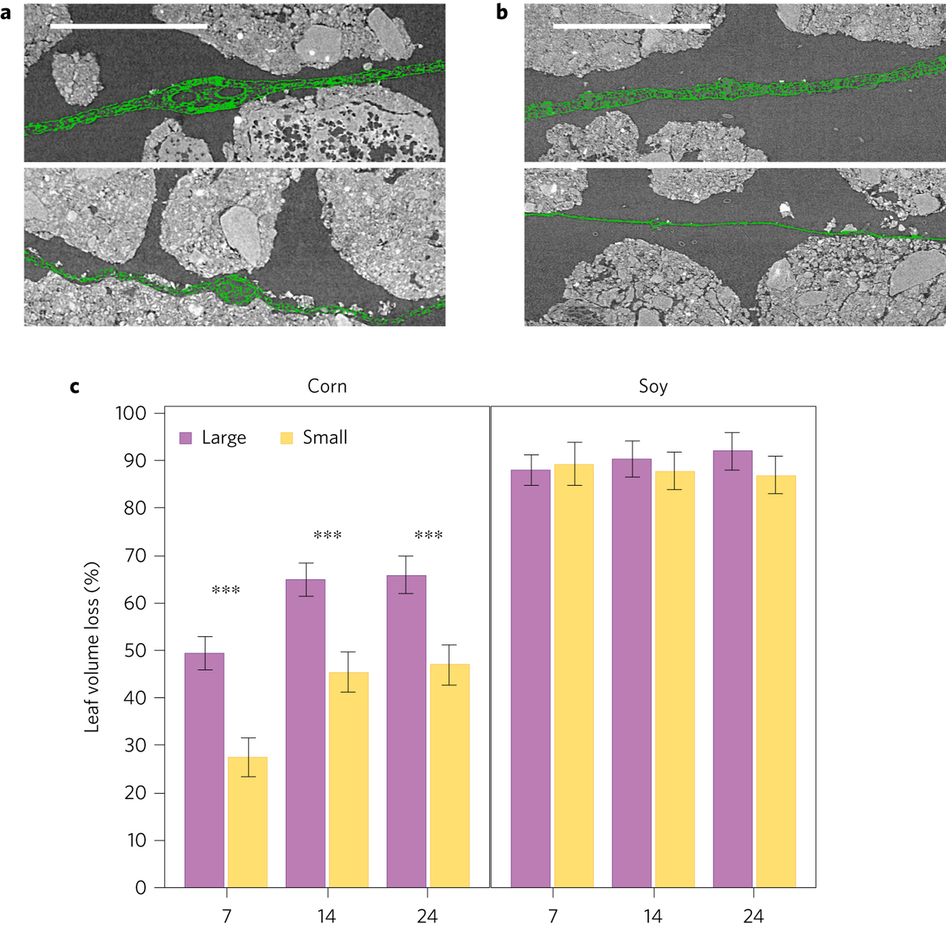

To unlock the secrets of these N2O hotspots, Kravchenko and her team took soil samples from MSU’s Kellogg Biological Station Long-term Ecological Research site. Then, in partnership with scientists from the University of Chicago, they examined the samples at the Argonne National Laboratory APS, employing the University of Chicago’s GeoSoilEnviroCARS 13-BM-D synchrotron x-ray beamline, a much, much more powerful version of a medical computerized tomography scanner. The intense x-rays penetrated the soil and allowed the team to accurately characterize the environments where N2O is produced and emitted. (The APS is an Office of Science user facility.)

“We found that hotspot emissions happen only when large soil pores are present,” Kravchenko said. “The leaf particles act as tiny sponges in soil, soaking up water from large pores to create a micro-habitat perfect for the bacteria that produce nitrous oxide.”

Not as much N2O is produced in areas where smaller pores are present. Small pores, such as in clay soils, hold water more tightly so that it cannot be soaked up by the leaf particles. Without additional moisture, the bacteria are not able to produce as much nitrous oxide. Small pores also make it harder for the gas produced to leave the soil before being consumed by other bacteria.

“This study looked at the geometry of pores in soils as a key variable that affects how nitrogen moves through those soils,” said Enriqueta Barrera, program director in NSF’s Earth Sciences Division. “Knowing this information will lead to new ways of reducing the emission of nitrous oxide from agricultural soils.”

More specifically, future research will review which plant leaves contribute to higher N2O emissions. Plants with more nitrogen in their leaves, such as soybeans, will more than likely give off more N2O as their leaves decompose. Researchers also will look at leaf and root characteristics and see how they influence emissions.

See: A. N. Kravchenko1*, E. R. Toosi1, A. K. Guber1, N. E. Ostrom1, J. Yu2, K. Azeem3, M.L. Rivers4, and G. P. Robertson1, “Hotspots of soil N2O emission enhanced through water absorption by plant residue,” Nat. Geo., published online 05 June 2017. DOI: 10.1038/ngeo2963

Author affiliations: 1Michigan State University, 2Hubei University, 3The University of Agriculture, 4The University of Chicago

Correspondence: *kravche1@msu.edu

Funding has been provided by the NSF's Long-Term Ecological Research Program (DEB 1027253), by the NSF's Geobiology and Low Temperature Geochemistry Program (Award no. 1630399), by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (DOE Office of Science BER DE-FC02-07ER64494), by MSU's AgBioResearch (Project GREEEN), and by MSU’s Discretionary Funding Initiative. GeoSoilEnviroCARS is supported by the National Science Foundation - Earth Sciences (EAR - 1634415) and Department of Energy- GeoSciences (DE-FG02-94ER14466). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Note: This story also appeared on the NSF web site.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.