Methanotrophic bacteria found in oceans and lakes are capable of performing a challenging and industrially relevant reaction—converting methane gas to the liquid fuel methanol—with relative ease. Synthetic chemists have aspired to replicate nature’s success, but attempts to understand the enzymatic process have been thwarted by its biological complexity. Now, using time-resolved x-ray absorption spectroscopy at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) and a photocatalytic model system, researchers have revealed a detailed picture of the initial step of the process. These insights may help scientists design artificial catalytic systems for the sustainable generation of methane-based fuels.

The oxidation of methane to methanol is quite a feat considering methane’s strong C-H bonds. Current industrial approaches entail an energy intensive and multi-step process, while the bacterial production of methanol presents an attractive alternative carried out by methane monooxygenase (MMO) enzymes at ambient conditions.

These enzymes exist in an intricate protein environment. To simplify their studies, researchers from Argonne National Laboratory, the Institute of Chemical Research of Catalonia, and the Institut de Chimie Moléculaire et des Matériaux d’Orsay used a compound with two bridging iron metal centers previously developed to model the enzymatic core, abbreviated here as diiron(III,III).

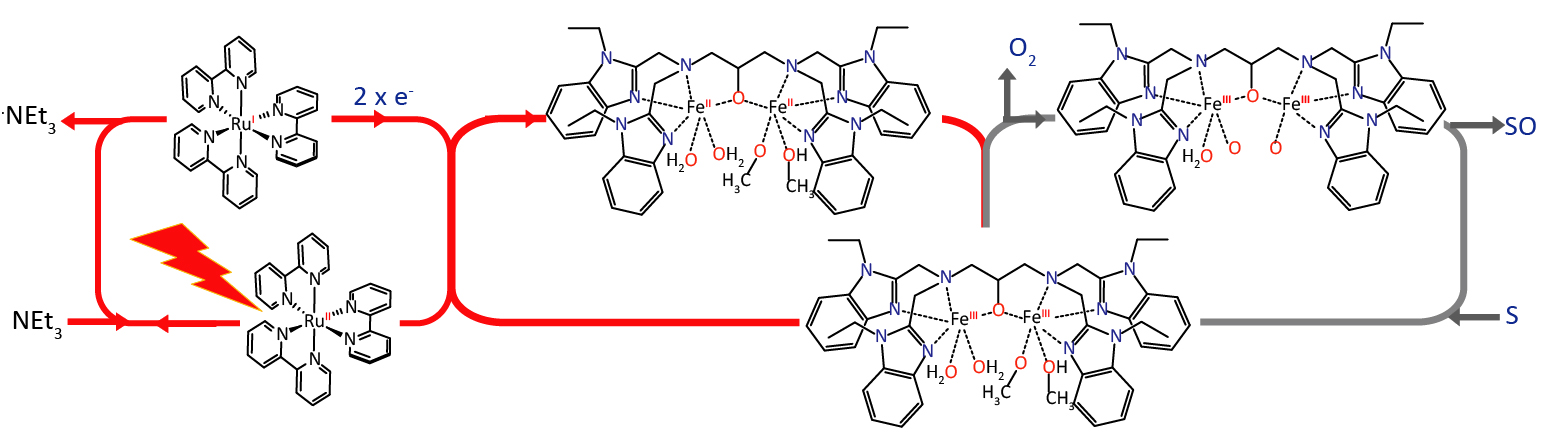

The researchers set out to investigate the first step of the reaction, in which the diiron(III,III) species gains two electrons to become a diiron(II,II) species — the key intermediate that can react with oxygen to form the highly reactive species responsible for the oxidation of methane to methanol.

The research team chose a mild photosensitizer called [Ru(bpy)3]2+ instead of the harsh chemical oxidants typically employed. [Ru(bpy)3]2+ absorbs light energy to transfer an electron to the iron catalyst, so studying its role in energy transfer could also be beneficial for artificial photosynthesis, an area that has garnered great research interest.

Using time-resolved x-ray absorption spectroscopy, the researchers could capture snapshots of the fast electron transfer between [Ru(bpy)3]2+ and the diiron(III,III) core which happens on the nanosecond timescale. By adding a sacrificial electron donor compound called triethylamine to prolong the lifetime of [Ru(bpy)3]2+, the researchers were able to induce a two-electron transfer process and generate the reduced diiron(II,II) species(Fig.1).

The electronic and structural configurations of the reduced diiron(II,II) core have been uniquely difficult to elucidate by two conventional spectroscopy methods. In ultraviolet-visible light spectroscopy, iron’s absorption signal would be overwhelmed by the photosensitizer’s absorption while in electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, iron’s high-spin character renders it essentially invisible. X-ray absorption spectroscopy sidesteps these limitations and has the advantage of being element specific, meaning that the beam’s energy range is tuned to iron and won’t pick up interference from other elements in the solution.

In this so-called pump-probe experiment, scientists shot a laser at the solution mixture, inducing an optical response that is then interrogated at ~150 ns intervals with incident X-rays to give spectral information. X-ray absorption data were collected at X-ray Science Division beamline 11-ID-D at the APS, which is an Office of Science user facility at Argonne. The researchers collected data at every time point enabling them to track the electron transfer and measure minute structural changes to the iron species, such as the elongation of bonds and shifting of the bond angles upon reduction, which is important for understanding the next steps in the reaction.

The team also modeled the structural configuration of the diiron(III,III) and diiron(II,II) species using density functional theory calculations and found that the experimental data matched well with their predictions.

These new insights into the reaction mechanism provide valuable guidance for the rational design of future catalysts capable of transforming methane to methanol. Next, the researchers plan to take the reduced iron species and begin introducing an easily oxidized methane analog, extending their understanding of the reaction one step further. — Tien Nguyen

See: Dooshaye Moonshiram1*, Antonio Picon1, Alvaro Vazquez-Mayagoitia1, Xiaoyi Zhang1, Ming-Feng Tu1, Pablo Garrido-Barros2, Jean-Pierre Mahy3, Frederic Avenier3, and Ally Aukauloo3,4, “Elucidating the light-induced charge accumulation in an artificial analogue of methane monooxygenase enzymes using time-resolved x-ray absorption spectroscopy,” Chem. Comm. 53, 2725 (2017). DOI: 10.1039/C6CC08748E

Author affiliations: 1Argonne National Laboratory, 2Institute of Chemical Research of Catalonia (ICIQ), 3Université Paris-Sud, Orsay, 4Institut de Biologie Intégrative de la Cellule

Correspondence: *dmoonshi@gmail.com

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences, Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences Division (contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357), and by LABEX CHARMMAT. This research used the resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility, at Argonne National Laboratory. P.G.B thanks “La Caixa” foundation for a Ph.D. grant. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02- 06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.