The Duke University press release by Karl Bates can be read here.

Bacterial cells have an added layer of protection, called the cell wall, that animal cells don't have. Assembling this tough armor entails multiple steps, some of which are targeted by antibiotics like penicillin and vancomycin. But one step in the process has remained a mystery because the molecular structures of the proteins involved were not known. Duke University School of Medicine researchers using the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne have now provided the first close-up glimpse of a protein, called MurJ, which is crucial for building the bacterial cell wall and protecting it from outside attack. They published MurJ's molecular structure in Nature Structural and Molecular Biology.

Antibiotic researchers feel an urgent need to gain a deeper understanding of cell wall construction to develop new antibiotics in the face of mounting antibacterial resistance. In the U.S. alone, an antibiotic-resistant infection called MRSA causes nearly 12,000 deaths per year.

“Until now, MurJ's mechanisms have been somewhat of a ‘black box’ in the bacterial cell wall synthesis because of technical difficulties studying the protein,” said senior author Seok-Yong Lee, associate professor of biochemistry at Duke University School of Medicine and senior author of the Nature Structural and Molecular Biology article. “Our study could provide insight into the development of broad spectrum antibiotics, because nearly every type of bacteria needs this protein's action.”

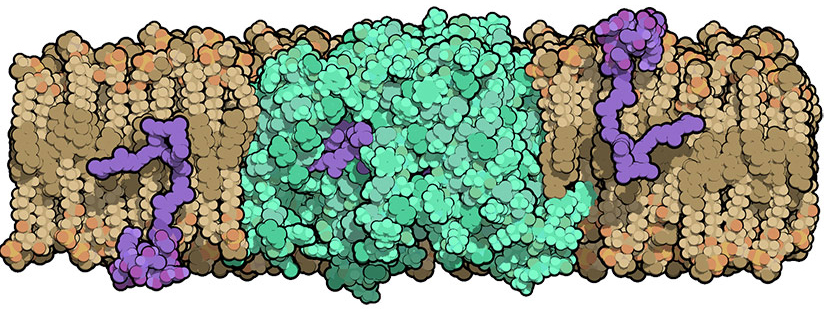

A bacterium's cell wall is composed of a rigid mesh-like material called peptidoglycan. Molecules to make peptidoglycan are manufactured inside the cell and then need to be transported across the cell membrane to build the outer wall.

In 2014, another group of scientists had discovered that MurJ is the transporter protein located in the cell membrane that is responsible for flipping these wall building blocks across the membrane. Without MurJ, peptidoglycan precursors build up inside the cell and the bacterium falls apart.

Many groups have attempted to solve MurJ's structure without success, partly because membrane proteins are notoriously difficult to work with.

In this new study, Lee's team was able to crystallize MurJ and determine its molecular structure to 2-angstrom resolution (a feat that is difficult to achieve in a membrane protein) via x-ray crystallography at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team 24-ID-C and 24-ID-E x-ray beamlines at the APS (the APS is an Office of Science user facility).

This structure, combined with follow-up experiments in which the scientists mutated specific residues of MurJ, allowed them to propose a model for how it flips peptidoglycan precursors across the membrane.

After determining the first structure of MurJ, Lee's team is now working to capture MurJ in action, possibly by crystallizing the protein while it is bound to a peptidoglycan precursor. “Getting the structure of MurJ linked to its substrate will be key. It will really help us understand how this transporter works and how to develop an inhibitor targeting this transporter,” Lee said.

Lee's group is continuing structure and function studies of other key players in bacterial cell wall biosynthesis as well. Last year, they published the structure of another important enzyme, MraY, bound to the antibacterial muraymycin.

See: Alvin C Y Kuk, Ellene H Mashalidis, and Seok-Yong Lee*, “Crystal structure of the MOP flippase MurJ in an inward-facing conformation,” Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol., Published online 26 December 2016. DOI: 10.1038/nsmb.3346

Author affiliation: Duke University School of Medicine

Correspondence: *seok-yong.lee@duke.edu

This work was supported by Duke startup funds (S.-Y.L.). The Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines are funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences from the National Institutes of Health (P41 GM103403). The Pilatus 6M detector on the 24-ID-C beamline is funded by a National Institutes of Health-Office of Research Infrastructure Programs HEI grant (S10 RR029205). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.