The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center press release by Deborah Wormser can be read here.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center researchers, in conjunction with colleagues from the University of Chicago, have developed a new imaging technique that makes x-ray images of proteins as they move in response to electric field pulses. The method could lead to new insights into how proteins work, said senior author Dr. Rama Ranganathan, of UT Southwestern. The technique had its first application in experiments at the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Laboratory. The results were published in Nature.

“Proteins carry out the basic reactions in cells that are necessary for life: They bind to other molecules, catalyze chemical reactions, and transmit signals within the cell,” said Ranganathan. “These actions come from their internal mechanics; that is, from the coordinated motions of the network of amino acids that make up the protein.”

Often, Ranganathan said, the motions that underlie protein function are subtle and happen on time scales ranging from trillionths of a second to many seconds.

“So far, we have had no direct way of ‘seeing’ the motions of amino acids over this range and with atomic precision, which has limited our ability to understand, engineer, and control proteins,” he said.

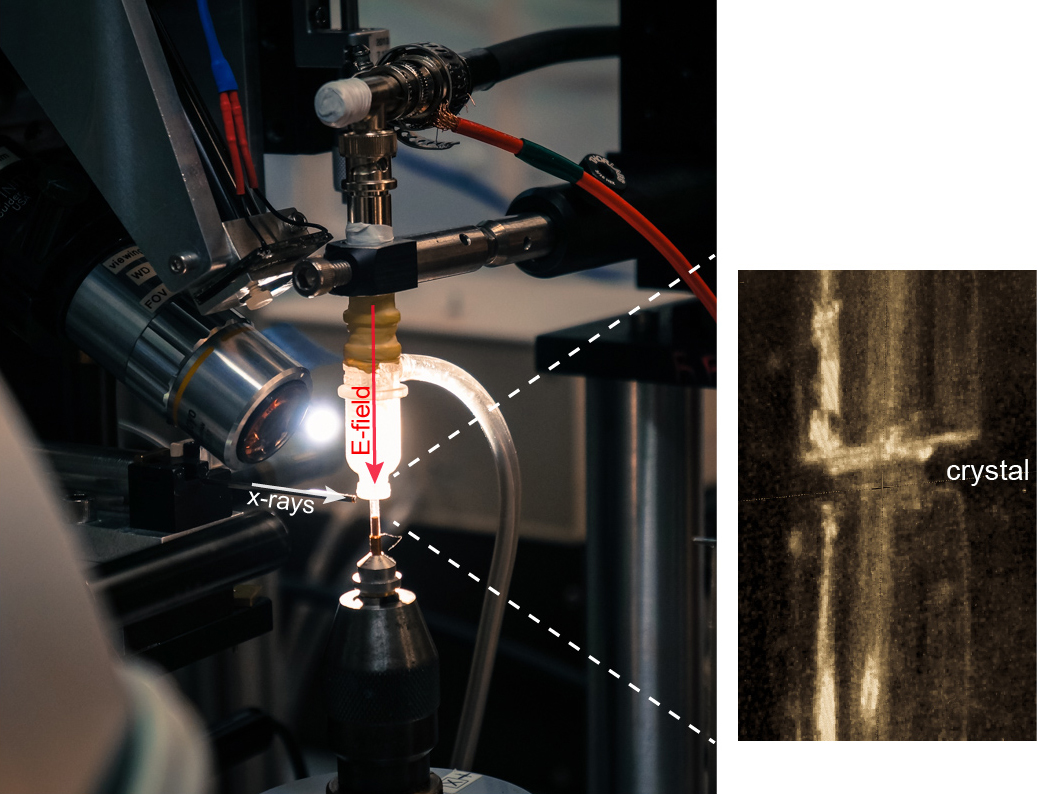

The new method, which the researchers call EF-X (electric field-stimulated x-ray crystallography), is aimed at stimulating motions within proteins and visualizing those motions in real time at atomic resolution, he said. This approach makes it possible to create video-like images of proteins in action – a goal of future research, he explained.

The method involves subjecting proteins to large electric fields of about 1 million volts per centimeter and simultaneously reading out the effects with x-ray crystallography, he said.

The researchers’ EF-X experiments utilizing the BioCARS 14-ID x-ray beamline at the APS, which is an Office of Science user facility, showed proteins can sustain these intense electric fields, and further that the imaging method can expose the pattern of shape changes associated with a protein’s function. Additional standard crystallography data (in the absence of electric field) were collected at beamline 11-1, at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource at the SLAC National Accelerator laboratory, also an Office of Science user facility,

“This is not the first report of seeing atomic motions in proteins, but previous reports were specialized for particular proteins and particular kinds of motions,” said Ranganathan. “Our work is the first to open up the investigation to potentially all possible motions, and for any protein that can be crystallized. It changes what we can learn.”

Ultimately, this work could explain how proteins work in both normal and disease states, with implications in protein engineering and drug discovery. An immediate goal is to make the method simple enough for other researchers to use, he added.

“I think this work has opened a new door to understanding protein function. It is already capable of being used broadly for many very important problems in biology and medicine. But like any new method, there is room for many improvements that will come from both us and others. The first step will be to create a way for other scientists to use this method for themselves,” Ranganathan said.

The group reports that they used the technique to study the PDZ domain of the human ubiquitin ligase protein LNX2, and found new information regarding how the protein actually works.

See: Doeke R. Hekstra1‡, K. Ian White1, Michael A. Socolich1, Robert W. Henning2, Vukica Šrajer2, and Rama Ranganathan1*, “Electric-field-stimulated protein Mechanics,” Nature 540, 400 (15 December 2016). DOI: 10.1038/nature20571

Author affiliations: 1UT Southwestern Medical Center, 2The University of Chicago ‡Present address: Harvard University

Correspondence: *rama.ranganathan@utsouthwestern.edu

R.R. acknowledges support from National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01GM123456, the Robert A. Welch Foundation (I-1366), the Lyda Hill Endowment for Systems Biology, and the Green Center for Systems Biology. BioCARS is supported by NIH grant R24GM111072 and through a collaboration with P. Anfinrud (NIH/ National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases). The SSRL is supported by the US Department of Energy (Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515) and by the NIH (P41GM103393). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract number DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.