Contrast agents that are selectively taken up by certain cells or tissues are widely used to enhance the effectiveness of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), especially for the detection of cancers. MRI offers high resolution and, unlike computer-aided tomography scans or positron emission tomography, MRI does not expose patients to radiation. Using x-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM) and x-ray absorption spectroscopy, researchers utilizing the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne have shown that a vanadium-based contrast agent greatly improves the detectability of colon cancers in mice. The vanadium compound accumulates preferentially in hot spots that appear to mark the presence of the most aggressive cancer cells. The work suggests that vanadium-based contrast agents used in conjunction with MRI could be a powerful tool for early cancer detection.

Earlier research established that a vanadium chelate, vanadyl bisacetylacetonate or VO(acac)2, increased the MRI signal from prostate cancers in mice, but the mechanism by which it did so was not known. A research team from the University of Chicago and Argonne undertook a further study to better understand how VO(acac)2 works, and compare it to Omniscan, a commercially available, gadolinium-based contrast agent. Omniscan is a sensitive agent for tracking blood flow, but it is not specific to cancer cells. For example, it produces a strong signal in benign fibroadenomas in the breast as well as in malignant breast tumors.

Omniscan remains in tissue only for a short time, whereas VO(acac)2 lingers for at least two hours. The two agents were, therefore, injected into test mice at different times, 10 minutes and 120 minutes respectively, before colon tissue samples could be extracted.

Working at the X-ray Science Division (XSD) beamline 2-ID-E at the APS, an Office of Science user facility, the team conducted rapid XFM scans, with 5-μm resolution, on tissue samples measuring 2 mm x 2 mm. These scans demonstrated that both gadolinium and vanadium could be mapped by XFM, and enabled the researchers to pick out for further study areas showing a noticeable signal from either of those elements. Tissue samples from control mice, without cancer, showed the expected anatomical structures but had no interesting concentrations of either gadolinium or vanadium.

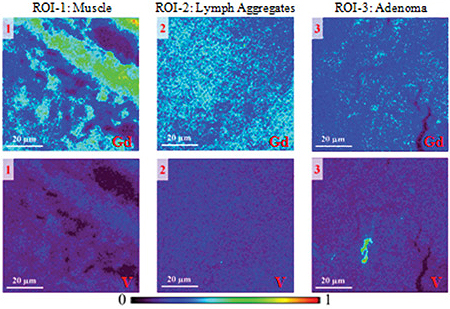

Examination of tissue samples from mice with cancer revealed a very different story. The team compared three types of tissue: muscle, lymphoid aggregates, and adenoma (tumor). High-resolution (0.3 μm) XFM of these selected regions showed that gadolinium accumulated mainly in the first two tissue types, and hardly at all in the cancerous material.

Vanadium did the opposite, making a clear distinction between the cancerous and normal regions. Moreover, the vanadium signal in the cancerous tissue was not uniform, but concentrated in a number of discrete hot spots. High-resolution XFM scans of these hot spots indicated that vanadium accumulated within cancer cells. Gadolinium, on the other hand, remained outside cells.

These findings are consistent with laboratory cell culture studies suggesting that vanadyl chelates such as VO(acac)2 are taken up by cells in proportion to their rate of glycolysis, the metabolic mechanism by which cells derive energy from glucose. Fast-growing cancer cells have high glycolysis rates, making it plausible that VO(acac)2 would be selectively taken up by cancers and therefore would be a good contrast agent for cancer detection.

In addition, the detection of hot spots in the vanadium signal from tumor tissue — and the fact that such hot spots were not found in any sample of non-cancerous tissue — suggests that VO(acac)2 has the virtue of picking out the most aggressive cell growth areas within a tumor.

As a final check, the team conducted x-ray absorption spectroscopy (in particular x-ray absorption near edge structure) measurements on tissue samples at XSD beamline 8-BM, and found that vanadium accumulating in cancerous cells remained in the +4 oxidation state; this is the paramagnetic oxidation state that produces contrast on MRI. This test confirmed that vanadium continues to be a good contrast agent even after it has been absorbed into a cell.

In newer work, the researchers are testing the usefulness of VO(acac)2 for other types of cancers in mice, and are working with chemists at Northern Michigan University to develop other vanadyl chelates that would have an even better tissue selectivity.

See: Devkumar Mustafi1*, Jesse Ward2, Urszula Dougherty1, Marc Bissonnette1, John Hart1, Stefan Vogt2, and Gregory S. Karczmar1, “X-Ray Fluorescence Microscopy Demonstrates Preferential Accumulation of a Vanadium-Based Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agent in Murine Colonic Tumors,” Mol. Imaging 14, 1535-1 (2015). DOI: 10.2310/7290.2015.00001

Author affiliations: 1The University of Chicago, 2Argonne National Laboratory

Corresponding author: *dmustafi@uchicago.edu

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1-CA133490 and RO1-CA167785) and by a University of Chicago Cancer Comprehensive Center grant. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation’s first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America’s scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.