A recent outbreak of respiratory illness in children in the U.S. has been linked to the enterovirus D68 (EV-D68). Enteroviruses are a class of viruses that include human rhinovirus, which causes the common cold, and poliovirus. Most enteroviruses are stabilized by a molecule that occupies a binding pocket found in the protective shell of the virus. When the virus binds to a human cell, this molecule is squeezed out of its pocket, destabilizing the virus. The virus then disintegrates and releases its genetic material into the cell, where it replicates and, ultimately, causes infection. The first strain of EV-D68 was isolated in 1962. Researchers used x-ray crystallography at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), an Office of Science user facility, to determine the crystal structure of this strain by itself and when bound to the anti-viral drug pleconaril, which they discovered was effective against the 1962 strain. Comparing the crystal structures with and without pleconaril indicates that the drug displaces a fatty acid contained within the hydrophobic pocket of the 1962 strain. While current strains of EV-D68 are mostly not inhibited by pleconaril—the drug has recently been found to be effective in some cell types, but not others—the researchers hope that the crystal structures they have obtained can inspire small modifications to the drug to make it an effective treatment against modern versions of EV-D68.

In August 2014, an outbreak of mild-to-severe respiratory illnesses struck thousands of children in the U.S. More than 1100 cases were confirmed to have been caused by enterovirus 68 (EV-D68), which has also been associated with around 100 cases of polio-like neurological illness. Enteroviruses belong to Picornaviridae, a large family of small viruses, many of which are human pathogens, including rhinoviruses, which cause the common cold, polioviruses, and coxsackieviruses.

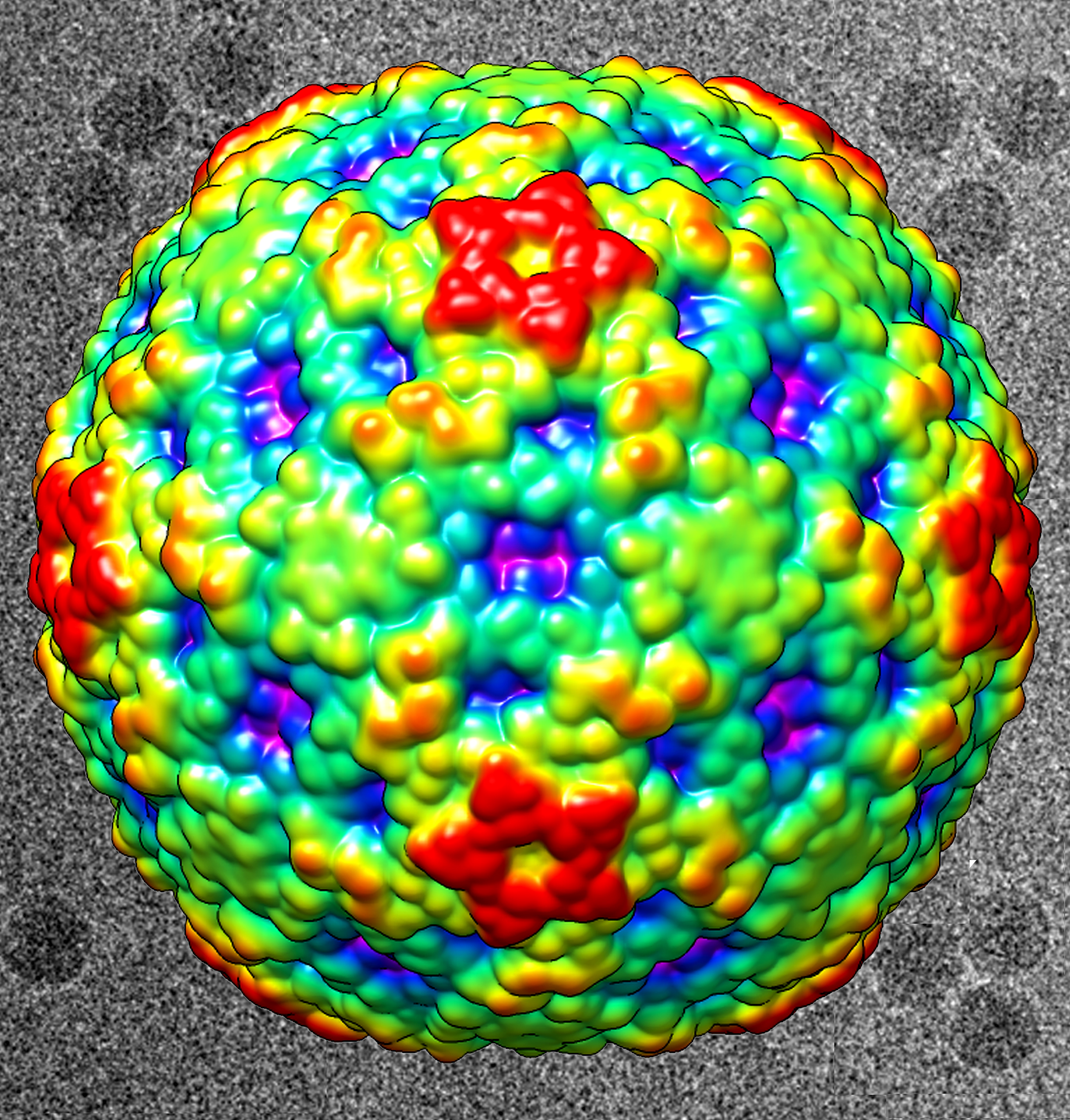

While the species EV-D remains poorly characterized, many enteroviruses have been well described structurally and functionally. Most infectious enteroviruses are stabilized by molecules called “pocket factors” located within a hydrophobic pocket of the virus's capsid, or protective shell. When the virus attaches to a human cell, the pocket factor is squeezed out of its pocket, causing the virus to disintegrate and release its genetic material into the cell. Once in the cell, the virus replicates and, ultimately, causes infection. Strategies to combat enteroviruses include finding compounds that permanently displace the pocket factor, preventing the virus from releasing its genetic payload.

EV-D68 was first isolated in 1962. During subsequent decades, efforts to identify a compound to neutralize a variety of rhinoviruses led to the discovery in the 1990s of pleconaril, an anti-viral found to be effective at inhibiting rhinovirus infection. However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration never approved pleconaril, primarily because it put women using birth control drugs at risk of conception.

Researchers from Purdue University became interested in studying pleconaril's potential effectiveness against EV-D68 after an outbreak of about 20 cases of acute flaccid paralysis was reported in California between 2012 and 2014. The researchers demonstrated that pleconaril was effective against the 1962 strain of EV-D68 in cell culture.

In order to discover just how the compound works, the researchers used x-ray crystallography at the BioCARS beamline 14-BM-C at the Argonne APS to learn the structure of the original strain of EV-D68 on its own, precise down to 2.0-Å resolution, and in complex with pleconaril, precise down to 2.3-Å resolution.

The crystal structures revealed that pleconaril replaces a fatty acid tucked into EV-D68’s hydrophobic binding pocket. The size and location of the fatty acid pocket factor lodged in the virus’s pocket are similar to those found in human rhinoviruses and different from those of the pocket factors found in viruses such as poliovirus 1 and EV-A71. This result is in alignment with the observation that pleconaril is far more active when the natural pocket factor is short, as in the human rhinoviruses and in EV-D68.

To investigate why pleconaril is more effective against EV-D68 than the anti-viral compounds pirodavir or BTA-188, the researchers performed computer simulations of the three compounds docking in the virus’s pocket. The presence of an aromatic chemical group called oxadiazole in pleconaril, rather than more hydrophilic groups found at structurally equivalent positions in either pirodavir or BTA-188, probably contributes to more favorable interactions of pleconaril with the hydrophobic residues deep inside the pocket of EV-D68.

Although EV-D68 has emerged as a considerable global public health threat, there is currently no available vaccine or effective antiviral treatment. The new crystal structures of EV-D68 alone and bound to pleconaril may suggest potential alterations to the drug to make it effective against current strains of the virus.

— Chris Palmer

See: Yue Liu, Ju Sheng, Andrei Fokine, Geng Meng, Woong-Hee Shin, Feng Long, Richard J. Kuhn, Daisuke Kihara, and Michael G. Rossmann*, “Structure and inhibition of EV-D68, a virus that causes respiratory illness in children,” Science 347(6217), 71 (2 January 2015). DOI: 10.1126/science.1261962

Author affiliation: Purdue University

Correspondence: *mr@purdue.edu

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant award AI11219 to M.G.R. BioCARS is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number R24GM111072. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.