The original UT Southwestern Medical Center press release by James Beltran can be read here.

A scientific blueprint to end tobacco cravings may be on the way after researchers using the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) determined the molecular structure of a protein that holds answers to how nicotine addiction occurs in the brain. The breakthrough by the researchers, from the Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center comes after decades of failed attempts to crystallize and determine the 3D structure of a protein that scientists expect will help them develop new treatments by understanding nicotine’s molecular effects.

“It’s going to require a huge team of people and a pharmaceutical company to study the protein and develop the drugs, but I think this is the first major stepping stone to making that happen,” said Ryan Hibbs, Assistant Professor of Neuroscience and Biophysics with the O’Donnell Brain Institute at UT Southwestern Medical Center, who co-authored the findings published in Nature.

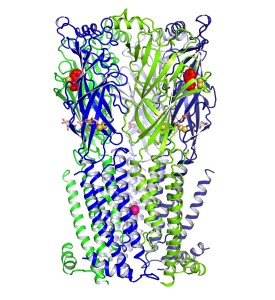

The protein, called the α4β2 (alpha-4-beta-2) nicotinic receptor, sits on nerve cells in the brain. Nicotine binds to the receptor when someone smokes a cigarette or chews tobacco, causing the protein to open a path for ions to enter the cell. The process produces cognitive benefits such as increased memory and focus but is also highly addictive.

Until the new findings were generated, scientists didn’t have a way to examine at atomic resolution how nicotine achieves these cognitive and addictive effects.

The expectation is that the 3D structures, obtained at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team (NE-CAT) 24-ID-C molecular crystallography facility at the Argonne National Laboratory APS, will help researchers understand how nicotine influences the activity of the receptor and lead to a medication that mimics its actions in the brain.

The finding may also have benefits in creating medications for certain types of epilepsy, mental illness, and dementia such as Alzheimer’s, which are also associated with the nicotinic receptor. However, Hibbs cautioned that testing of any ensuing treatment would likely take many years.

Studies have shown smoking cessation drugs have mixed results in treating nicotine addiction, as have other methods such as nicotine patches and chewing gum.

Despite widespread education on the dangers of tobacco use, it still causes nearly 6 million deaths per year worldwide, with smoking the leading cause of preventable death, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarettes alone account for 1 in 5 deaths annually in the U.S.

Those statistics are among the motivating factors for Hibbs, whose laboratory team began researching how to determine the structure of the receptor in 2012.

The receptor is “a critically important therapeutic target” for addiction and various mental and neurological disorders, said Joseph Takahashi, Chairman of Neuroscience and Investigator for the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. “This is a major advance and solves a longstanding problem in crystallizing” the nicotinic receptor, said Takahashi, who holds the Loyd B. Sands Distinguished Chair in Neuroscience.

For years, scientists around the globe had concentrated efforts on the receptor found in the electric organ of a Torpedo ray, a rich source of nicotinic receptors that yielded a wealth of biochemical information and held promise for obtaining a high-resolution atomic map of the protein.

“But they were never able to get the Torpedo protein to crystalize,” Hibbs said, explaining that the protein from the ray proved too unstable and couldn’t be genetically modified. “Many very good research groups had tried to do this and failed. We took a different approach.”

Instead, UT Southwestern researchers developed a method for mass producing nicotinic receptors by viral infection of a human cell line. The team inserted genes encoding the proteins that make the receptor into the virus, and the infected human cells started producing large amounts of the receptor.

They then used detergent and other purification steps to separate the receptor from the cell membrane and wash away all other proteins. Researchers were left with milligrams of the pure receptor that they mixed with chemicals known to promote crystallization.

The team looked at thousands of chemical combinations before eventually being able to grow crystals of the receptor, bound by nicotine and about 0.2 mm long. Lastly, they used x-ray diffraction measurements at NE-CAT to obtain a high-resolution structure of the receptor (Fig. 1).

The team’s next steps involve determining structures in the absence of nicotine, and in the presence of molecules with different functional effects. Comparisons between structures will allow them to understand better what nicotine does, and how its actions are distinct from those of other chemicals, said Hibbs.

See: Claudio L. Morales-Perez, Colleen M. Noviello, and Ryan E. Hibbs*, “X-ray structure of the human α4β2 nicotinic receptor,” Nature, published online 03 October 2016. DOI: 10.1038/nature19785

Author affiliation: University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Correspondence: *ryan.hibbs@utsouthwestern.edu

This research project was supported by an NIH training grant (T32 NS069562) and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Gilliam Fellowship to C.L.M.-P.; R.E.H. is supported by a McKnight Scholar Award, a Klingenstein-Simons Fellowship Award in the Neurosciences, The Welch Foundation (I-1812), The Friends of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center and the NIH (DA037492, DA042072 and NS077983). funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences from the National Institutes of Health (P41 GM103403). The Pilatus 6M detector on 24-ID-C beam line is funded by a NIH-ORIP HEI grant (S10 RR029205). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory seeks solutions to pressing national problems in science and technology. The nation's first national laboratory, Argonne conducts leading-edge basic and applied scientific research in virtually every scientific discipline. Argonne researchers work closely with researchers from hundreds of companies, universities, and federal, state and municipal agencies to help them solve their specific problems, advance America's scientific leadership and prepare the nation for a better future. With employees from more than 60 nations, Argonne is managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit the Office of Science website.