The original University of Vermont press release by Joshua E. Brown can be read here.

X-rays have long been used to make pictures of tiny objects, even single atoms. Now a team of scientists, with a big assist from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne, has discovered a new use for x-rays at the atomic scale: using them like a radar gun to measure the motion and velocity of complex and messy groups of atoms.

"It's a bit like a police speed trap, but for atomic and nanoscale defects," says Randall Headrick, a professor of physics at the University of Vermont who led the research team. The new technique was reported on March 28 in the journal Nature Physics.

X-rays have great power to look within. But as scientists probe the structure of ever-smaller things, including chains of DNA, viruses, and individual atoms, the random arrangement of those objects makes it increasingly difficult to distinguish between them. A long-standing problem has been that good x-ray images obtained with standard sources of x-rays, require nearly perfect crystals — identical objects in precise order. At the scale of atoms, complex and disordered objects —like the thin films that are used to make the screen on a cell phone or the metal layers used in electronic circuits — give a blurry x-ray picture. "It's like blending many different faces in a composite image," Headrick said, "or trying to see what an average car looks like by watching traffic zip along a highway."

In a new approach, Headrick and the other scientists in the team, from the University of Vermont, Boston University, and Argonne, impose order on the x-rays when there isn't order in what they're looking at. They used coherent x-rays (think x-rays traveling in a marching band) at the X-ray Science Division x-ray beamline 8-ID-I at the APS, an Office of Science user facility, to recover some of the information from their picture. Rather like radar picks out an individual's speed on the highway, they fished out the distinct speeds of small groups of atoms from the bulk x-ray signal they were shining onto a stream of atoms in motion. And in that new kind of x-ray image, they discovered voids and tiny pores that form when making two kinds of thin films with silicon and tungsten and how those voids and pores move.

Their discovery promises to improve industrial techniques for making smoother, more perfect thin films, which have thousands of commercial applications from solar panels to drug delivery systems, computer chips to potato chip bags.

But far more important, Headrick said, the research opens a new way to view many kinds of complex clumps of atoms in motion, not just tidy crystals.

"We can see these nanoscale defects form in the film while they are being made," Headrick said. The scientists were surprised that they were able to create a view not just of the surface roughness of the film, but also the interior structure. This is important since the quality of thin films can be strongly affected by the dynamic relationship between how they are growing at the surface (often being sprayed or deposited in a vacuum) and the structure of atoms forming beneath the surface.

"We find that there are two kinds of defects," Headrick said, "one type that moves along with the surface and is thought to be nanocolumns that grow with the surface, and another type that is voids that do not grow with the surface."

To understand these two kinds of defects, pour yourself a glass of beer and watch the bubbles. Some move in thin lines through the liquid, traveling up while the top of the beer also rises. Other bubbles, trapped in the foamy head, are stuck in place while more foam piles on top of them.

Now imagine that these bubbles are actually single atoms. The lines of bubbles that move up while the beer is being poured are like the nanocolumns of atoms Headrick and the team observed with the new x-ray technique. The voids in the film are like the bubbles trapped in the beer foam.

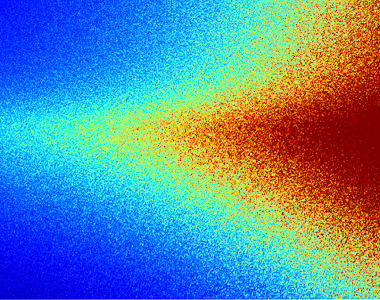

The lead author on the paper is Headrick's graduate student, Jeffrey Ulbrandt. Together, they collaborated with researchers from Boston University, including physicist Karl Ludwig, and scientists at Argonne, to make the discovery. Imaged with the coherent x-rays from the 8-ID-I beamline, disordered objects — like the rough surface and jumbled interior of a silicon film — can be sensed in a complex pattern of speckles that is made on an x-ray detector. "This speckle pattern contains detailed information on the shapes and spacings of the collection of objects," Headrick said.

These coherent x-rays can also sense motion, tracking jiggling and swarming groups of atoms that are moving independently and erratically. The new study pushes that realization forward. The scientists took a scattered wave of x-rays bouncing off the rough surface of the thin film being deposited in a vacuum chamber and mixed it with a scattered wave of x-rays coming off the disordered defects — the nanocolumns and voids — forming at and beneath the film's surface.

These two mixed waves work a bit like a radar gun. The waves from the surface form a speed reference — while the subsurface waves form a much smaller signal mixed into this reference wave. The scientists looked at the speckled pattern from x-rays scattering off the growing surface of the thin films, getting thicker at a known rate. Then they measured how this speckled pattern oscillated when interacting with the x-rays bouncing off the defects and interior. These oscillations ("like a vibrating tuning fork," Headrick said) are caused by atoms going different speeds — which gave the team a sensitive measure of the relative velocities of atoms in motion. But instead of 55 mph, the thin film surface grows up at a few Angstroms per second. Some of the defects grow with it, while others get left in the nanodust.

"This is a new x-ray effect," Randy Headrick said, "that lets us sense disordered matter in motion at the atomic scale."

See: Jeffrey G. Ulbrandt1, Meliha G. Rainville2, Christa Wagenbach2, Suresh Narayanan3, Alec R. Sandy3, Hua Zhou3, Karl F. Ludwig, Jr.1, and Randall L. Headrick1*, “Direct measurement of the propagation velocity of defects using coherent X-rays,” Nat. Phys., advance online publication (28 March 2016). DOI: 10.1038/nphys3708

Author affiliations: 1University of Vermont, 2Boston University, 3Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: *rheadrick@uvm.edu

R.L.H. and J.G.U. were supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences (BES) under DE-FG02-07ER46380; C.W., K.F.L., and M.G.R. were supported by DOE-BES grant DE-FG02-03ER46037. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Related publication: Meliha G. Rainville, Christa Wagenbach, Jeffrey G. Ulbrandt, Suresh Narayanan, Alec R. Sandy, Hua Zhou, Randall L. Headrick, and Karl F. Ludwig, Jr., “Co-GISAXS technique for investigating surface growth dynamics,” Phys. Rev. B 92, 214102 (2015). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevB.92.214102

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.