The Earth’s atmosphere has a missing xenon problem. Compared to other atmospheric gases, the concentration of xenon is about 20 times less than one would expect. One explanation is that xenon is trapped in rocks underneath the Earth’s surface, but the trouble is that xenon doesn’t normally react with minerals. However, experiments at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) demonstrate how a certain porous material, Ag-natrolite, behaves like a trap door for xenon. At high pressure and moderate temperatures, pores open to let xenon in, subsequently trapping it once the pressure is released. The researchers suggest that porous materials like this may have captured xenon from the atmosphere long ago and sequestered it somewhere in the Earth’s mantle.

Xenon is a trace gas in the Earth's atmosphere, occurring at the level of around 1 part per 10 million. This is much lower than the concentration of xenon found in very old meteorites, which are believed to be representative of the Solar System’s original elemental abundances. For several decades, planetary scientists have pondered where the xenon may have gone. It is too heavy to have escaped into space, so the most likely hiding place is somewhere underground. But xenon is one of the noble gases, and like its noble cousins (helium, neon, argon, and krypton), its electrons are all in filled orbitals, which means it does not easily form chemical bonds.

However, xenon is not completely unreactive. It is highly polarizable – in comparison to the other noble gases – and this polarization can lead to chemical bonds and physical interactions, for example with surfaces. Recent work has shown that xenon does interact with silicates at high pressure and high temperature. And other experiments have shown that xenon adsorbs at high pressure and temperature inside the pores of aluminosilicate materials called zeolites. Up until now, this zeolite insertion has always been reversible – i.e., the xenon escapes as soon as the pressure is released.

But now a group of scientists from Yonsei University and Chung-Ang University (both in South Korea), the Carnegie Institution of Washington, the University of South Carolina, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have obtained the first evidence of irreversible xenon insertion. They found they could trap xenon in a small-pore zeolite called Ag-natrolite, or Ag-NAT for short, even after the pressure was released. The findings appeared in the journal Nature Chemistry.

The researchers performed high-pressure x-ray diffraction (HPXRD) experiments at x-ray beamline 16-BM-D of the High Pressure Collaborative Access Team (HP-CAT) at the Argonne APS (the APS is an Office of Science user facility). First they annealed the Ag-NAT samples at 250° C, and then placed them in a diamond anvil cell, where the pressure was ramped up in the presence of xenon gas.

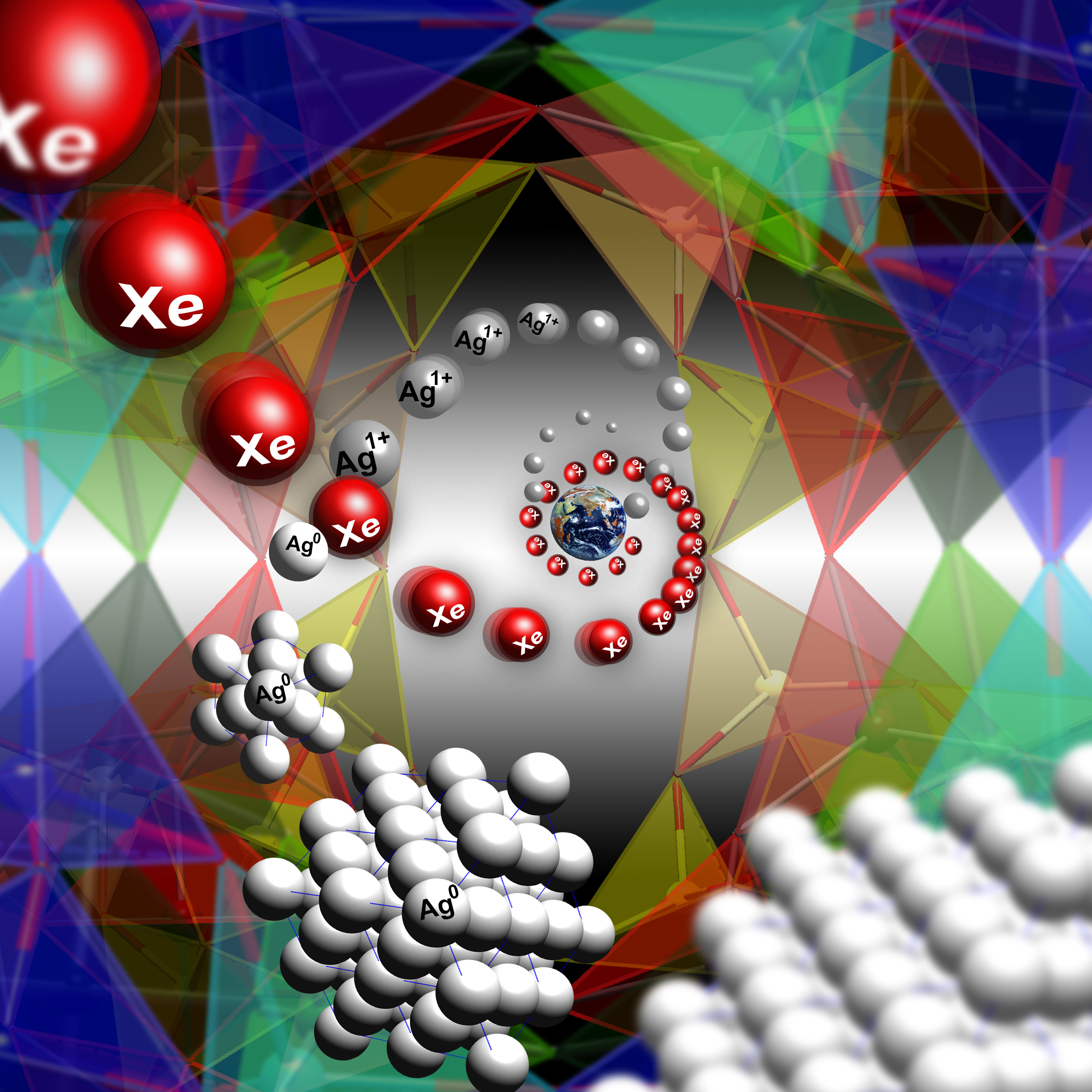

The resulting diffraction images showed the crystal structure of Ag-NAT changes at 1.7 gigapascals (about 17,000 atmospheres), going from an orthorhombic phase (with a rectangular-shaped unit-cell) to a monoclinic phase (with a slanted unit cell). The pressure and temperature changes result in a 3.2% volume expansion of the material and a widening of the pores, which allows xenon atoms to enter and adsorb. This was confirmed using the x-ray diffraction, which showed evidence that xenon was present in the pores of Ag-NAT at pressures of 1.7 gigapascals after heating to 250o C (see the figure). At the same time, it was shown that silver atoms leave the pores of the Ag-NAT material and form silver nanoclusters.

When the samples were removed from the cell and returned to normal pressures and temperatures, some of the xenon remained trapped inside the Ag-NAT material. The xenon only escaped when the samples were re-heated.

The team performed a similar set of experiments using the noble gas krypton instead of xenon. In this case, HPXRD measurements performed at the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory in South Korea revealed that krypton also enters into the Ag-NAT pores at high pressures and temperatures, but de-adsorbed as soon as the pressure was removed.

The preferential capture of xenon by a porous silicate material suggests that a trapdoor mechanism may account for the missing xenon in the Earth’s atmosphere. High pressures and temperatures exist in subduction zones, where tectonic plates collide and sink into the mantle. In these zones, there may be silicate materials with structures similar to that of Ag-NAT that can capture xenon and lock it away deep underground. — Michael Schirber

See: Donghoon Seoung1, Yongmoon Lee1, Hyunchae Cynn2, Changyong Park3, Kwang-Yong Choi4, Douglas A. Blom5, William J. Evans2, Chi-Chang Kao6, Thomas Vogt5, and Yongjae Lee1*, “Irreversible xenon insertion into a small-pore zeolite at moderate pressures and temperatures,” Nat. Chem. 6, 835 (September 2014). DOI: 10.1038/NCHEM.1997

Author affiliations: 1Yonsei University, 2Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, 3Carnegie Institution of Washington, 4Chung-Ang University, 5University of South Carolina, 6SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Correspondence: * yongjaelee@yonsei.ac.kr

This work was supported by the Global Research Laboratory Program of the Korean Ministry of Science, ICT and Planning (MSIP) and was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy (contracts W-7405-Eng-48 and DE-AC52-07NA27344). Experiments using the synchrotron were supported by MSIP's PAL-XFEL project. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.