The North Carolina State University press release can be read here.

The first entropy-stabilized alloy that incorporates oxides — and demonstrates conclusively that the crystalline structure of the material can be determined by disorder at the atomic scale rather than chemical bonding — has been realized by researchers from North Carolina State University and Duke University with an assist from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne.

“High entropy materials research has been a hot field since 2007, but no one reported that the unique structure of these materials was indeed stabilized by configurational disorder alone - and no one had created an entropy-stabilized material using anything other than metals,” said Jon-Paul Maria, a professor of material science and engineering at NC State and a corresponding author of a Nature Communications paper on the new findings.

“While the influence of entropy is present in the natural world — for example, the arrangement of metal ions in feldspar, one of the most common minerals in the Earth's crust — crystalline solids that are stabilized by entropy alone do not exist naturally,” Maria said. “We wanted to know if it was possible to stabilize an oxide using entropy and whether we could prove it. The answer was yes to both. Oxides were chosen for this study because they enabled us to directly test this entropy question.”

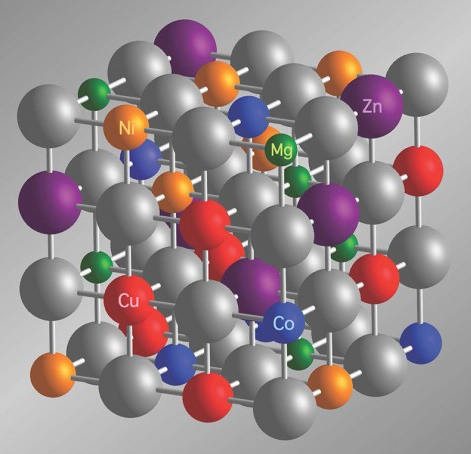

High-entropy alloys are materials that consist of four or more elements in approximately equal amounts. More importantly, these elements are distributed randomly at the atomic scale. They have garnered significant attention in recent years because they can have remarkable properties. But to understand entropy-stabilized alloys, one must understand the crystalline structure of materials.

A material's crystalline structure consists of a repeating arrangement of atoms, which can be different from material to material. That arrangement is called the crystal's “lattice type.” For example, think of one crystal as having its atoms arranged as a series of cubes. In a conventional material that contains multiple atom types, the arrangement is regular and ordered. Along one of those cube edges, the atoms would follow a regular repeat pattern. In an entropy-stabilized material, the relative arrangement is completely random.

By adding more and more different atom types to a crystal, you can generate more and more disorder if the arrangement of atoms on that lattice remains random. Finding the right mix of atoms that will retain this randomly mixed state is the key to entropy stabilization and testing the entropy question.

In this case, researchers created an entropy-stabilized material made up of five different oxides in roughly equal amounts: magnesium oxide, cobalt oxide, nickel oxide, copper oxide and zinc oxide. The individual materials were mixed in powder form, pressed into a small pellet, then heat treated at 1000° Celsius for several days to promote reaction and mixing.

The researchers then used the x-ray absorption fine structure technique at the X-ray Science Division 12-BM-B x-ray beamline at the APS, which is an Office of Science user facility, to determine that the constituent atoms in the entropy-stabilized oxide were evenly distributed and that their placement in the crystalline lattice structure was random. The material was also studied using x-ray diffraction and electron microscopy at the Analytical Instrumentation Facility at North Carolina State University.

“The data told us that each unit cell in the entropy-stabilized oxide's structure had the appropriate distribution of atoms, but that where each atom was located in a unit cell was random,” Maria said. “Making this determination is very difficult, and requires the most sophisticated characterization tools available at the APS.

“This is fascinating — we've proved that you can create entirely new crystalline phases of matter - but it's fundamental research,” Maria said. “A lot of additional work needs to be done to characterize the properties of these materials and what the potential applications may be.

“However, the work does tell us that we'll be able to engineer new materials in unusual ways - and that is very promising for developing materials with desirable properties.”

See: Christina M. Rost1, Edward Sachet1, Trent Borman1, Ali Moballegh1, Elizabeth C. Dickey1, Dong Hou1, Jacob L. Jones1, Stefano Curtarolo2**, and Jon-Paul Maria1*, “Entropy-stabilized oxides,” Nat. Commun. 6, 8485 (9 September 2015). DOI: 10.1038/ncomms9485

Author affiliations: 1North Carolina State University, 2Duke University

Correspondence: *jpmaria@ncsu.edu, **stefano@duke.edu

J-P.M., E.C.D. and C.M.R. acknowledge support from ARO under contract W911NF-14-0285. S.C. acknowledges partial support by the Department of Defense (ONR-MURI- N000141310635), the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) (DE-AC02-05CH11231, BES#EDCBEE), and the Duke Center for Materials Genomics and the aflowlib.org consortium. J-P.M. and S.C. acknowledge support from DOD (ONR-MURI-N00014-15-1-2863). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.